Representatives

Continental Europe: BOXERBOOKS, INC., Zurich

British Isles: PRENTICE-HALL INTERNATIONAL, INC., London

Australasia: PAUL FLESCH & CO., PTY. LTD., Melbourne

Canada: m.g. hurtig ltd., Edmonton

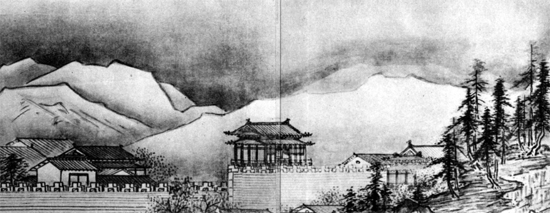

Reproduced with the kind permission of the owner,

Mr. Motomichi Mori, Yamaguchi Prefecture, from photographs

supplied by courtesy of the National Museum, Tokyo.

Published by the Charles E. Tuttle Company, Inc.

of Rutland, Vermont & Tokyo, Japan

with editorial offices at

Osaki Shinagawa-ku, Tokyo 141-0032

1959 by Charles E. Tuttle Co., Inc.

All rights reserved under the Berne

Convention and the Universal Copyright Convention

Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 59-14085

ISBN: 978-1-4629-0419-8 (ebook)

First printing, 1959

Sixth printing, 1968

Book design & typography by M. Weatherby

Manufactured in Japan

INTRODUCTION

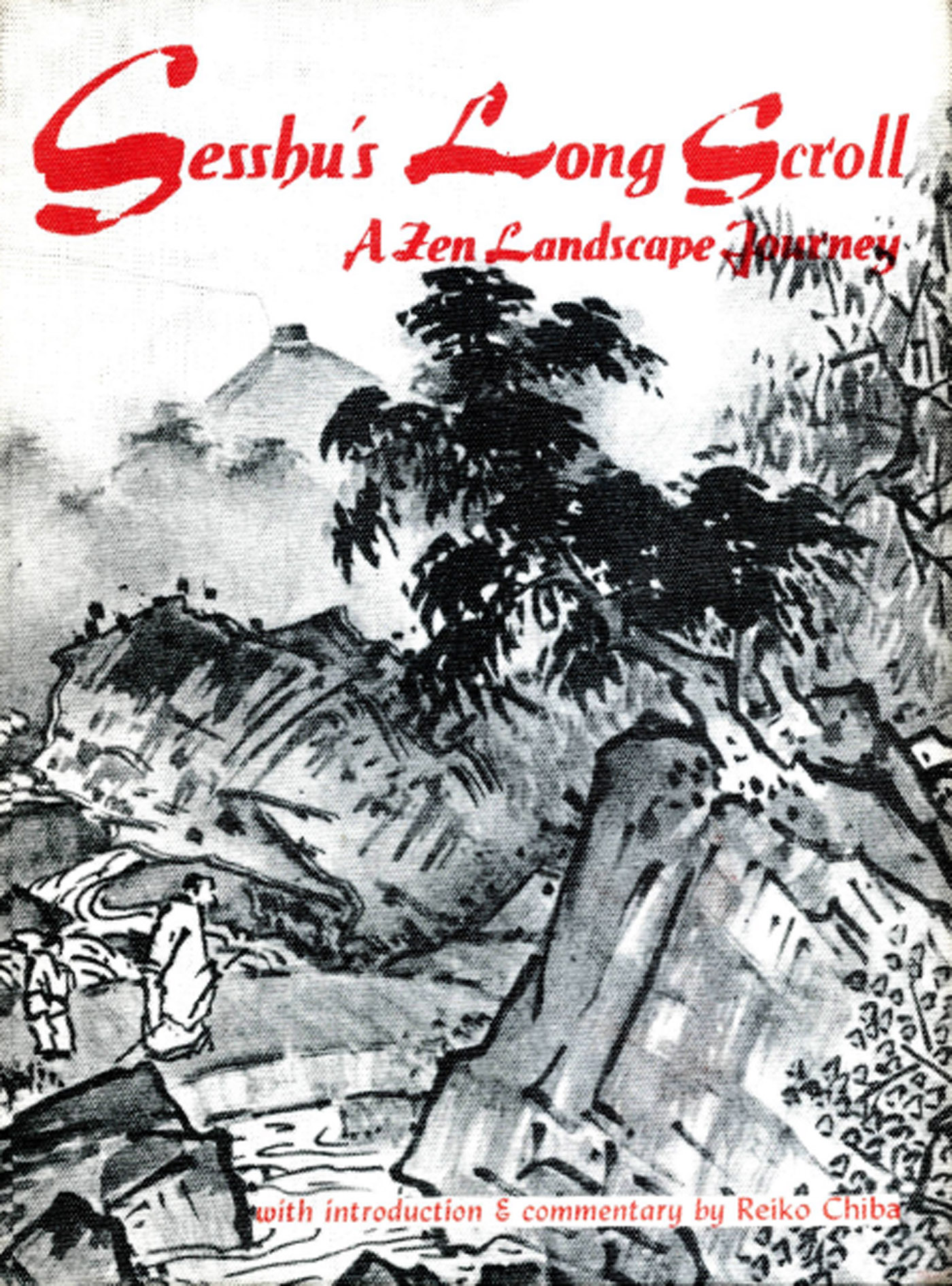

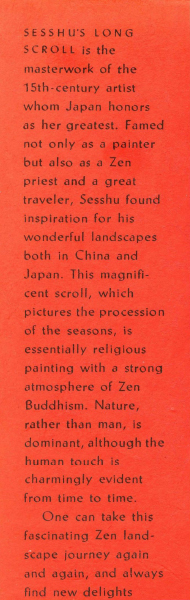

The Japanese value Sesshu as the greatest of all their artists, and the Long Landscape Scroll, here reproduced in its entirety, is his acknowledged masterpiece.

In considering Sesshu and his work, it is well to remember his concurrent role as a Zen priest. He was born in 1420 near Okayama, in the southern part of Japan's main island. Tradition says he was a rather unruly boy. His mother therefore must have felt a measure of relief in turning him over to the local Zen temple for training and discipline when he was about ten years old. Even the priests found him a bit hard to handle. The most famous myth concerning his youth records that after a particularly trying day his instructor was forced to punish him by tying him to a temple post. At the end of a few hours, Sesshu cried so bitterly that tears fell to his feet. Thereupon, with the tears as ink, he drew such a realistic rat in the dust that the rat came to life, gnawed the ropes, and set him free.

Sesshu, however, matured early and at the age of twenty advanced to the famous Sokoku-ji, a temple in Kyoto where he made rapid progress both as an artist and as a popular figure in the Zen denomination. A most important thing to remember about Sesshu is his versatility. He was a whole man in the sense that we in the West frequently associate with great Renaissance figures. Although a devout Zen Buddhist, he was in no sense a recluse or hermit. In addition to being a painter he was an accomplished poet and landscape gardener. While at the great Sokoku-ji he was selected to act as host and entertainer for visiting dignitaries. He was also a businessman, trusted with the purchase and evaluation of art objects and given considerable authority on one of the great contemporary trading expeditions to China. Sesshu enjoyed company and parties. He was an inveterate traveler, most famous in his day for his long journey to China but always restlessly on the move in Japan until the end of his long, full life at the age of eighty-six.

Although he admired, studied, and acknowledged his debt to Chinese masters, Sesshu was not a strict traditionalist. As he himself once said, not men, but mountains and rivers, were his teachers. Even in his own day he became a legend and was the founder of an extensive school. His fame today is secure, and a major portion of Japanese painters have acknowledged him as master.

Sesshu's work exhibits the three traditional brush-writing techniques: shin, gyo, and so. Shin is distinguished by an angular quality, firm and decisive strokes, and attention to linear detail; gyo, by curving lines and rounded forms resulting from more rapid use of the brush; and so, by a cursive, comparatively indistinct quality that achieves its effects through suggestion rather than literal interpretation. The Long Landscape Scroll, although celebrated as a display of Sesshu's shin technique, occasionally introduces aspects of atmosphere and relative distance that illustrate gyo and so.

The Long Landscape Scrol' was completed in I486, roughly six years before Columbus discovered America. In this reproduction, to conform to Western conventions of book reading, the scroll is presented going from the end toward the beginning, and Sesshu's inscription, which in the original concludes the scroll, comes at the end of the book. If you wish to view the scroll as it was painted, you should start from the end of the book and come forward to the first part. Essentially, however, there is little difference as far as enjoyment of the painting is concerned. Each part seems to fall of itself into a natural composition, requiring no strict sequence for proper appreciation. The only actual element of continuity is a gentle and gradual change of seasons from spring to winter. The original, done in ink and faint color washes on paper, is approximately 51 by 1feet in size. For those who desire to learn more about Sesshu and his art, the following books are recommended:

Covell, Jon Carter: Under the Seal of Sesshu. New York, 1941.

Grilli, Elise: Sesshu Toyo. Vol. Io, Library of Japanese Art. Tokyo, Japan & Rutland, Vermont, 1957.

Tokyo National Museum. Sesshu: Catalogue of Special Exhibition at the 450th Anniversary. Tokyo, 1956.

Sesshu's

Long

Scroll

As we start our journey through the Long Landscape Scroll, the season winter. This seems appropriate, for Sesshu, the painter's nom d'arriste weans "snowy boat." One pleasant story is that Sesshu chose this name upon leaving China, since so many well-wishers showered him with farewell poems that his boat seemed to be covered with snow. Actually, however, he had assumed this name several years before his trip to China. In Japanese the word "Sesshu" suggests the landscapes of which he was so fond. Its syllables recall the names of former artists he admired.

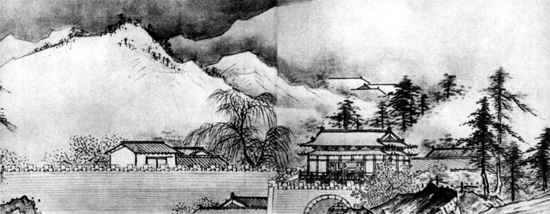

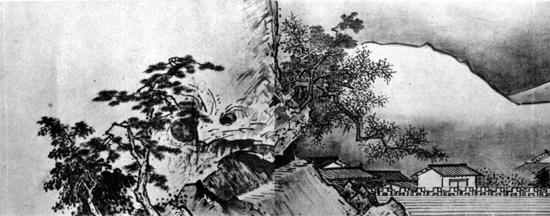

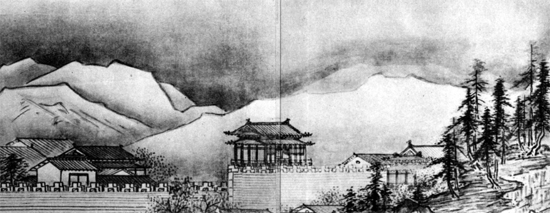

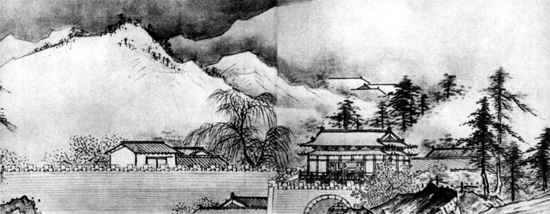

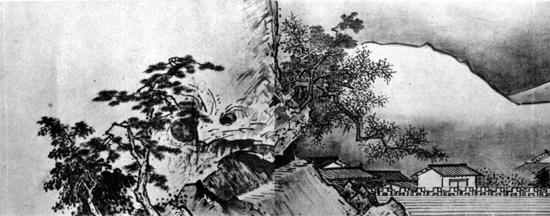

The Long Landscape Scroll is done almost entirely in the shin technique, the style most associated with Sesshu. The lines are firm, strong, and frequently angular, as we can see in the mountains that form the background of the village through which we are passing and in the rocks and cliffs we shall soon observe. There is considerable linear detail. We must keep in mind, while traveling through the scroll, that most of its inspiration comes from Chinese rather than Japanese landscapes. The stone wall, the temple, and the arched bridge (page 13) in the opening section are all typically Chinese. Probably because it is winter, we do not encounter anyone on the road. The first people we meet are the group of three resting comfortably inside the temple just above the arched bridge, where they themselves are in a position to see much of the same view that we admire. It is possible that Sesshu intended this group to represent a Zen priest with two of his disciples. Behind the temple, pine trees climb a snowy hill, and beyond them a few angular strokes suggest other buildings farther up. Large rocks rise in the foreground.