THE ORACLES OF THE THREE SHRINES

THE ORACLES OF THE THREE SHRINES

Windows on Japanese Religion

Brian Bocking

First Published 2001

by Routledge

Published 2013 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY, 10017, USA

Routledge is an Imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

2001 Brian Bocking

Typeset in Bembo by LaserScript Ltd, Mitcham, Surrey

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book has been requested

ISBN 13: 978-0-700-71384-4 (hbk)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original may be apparent.

In memoriam

Angus Lindsay

19492000

Contents

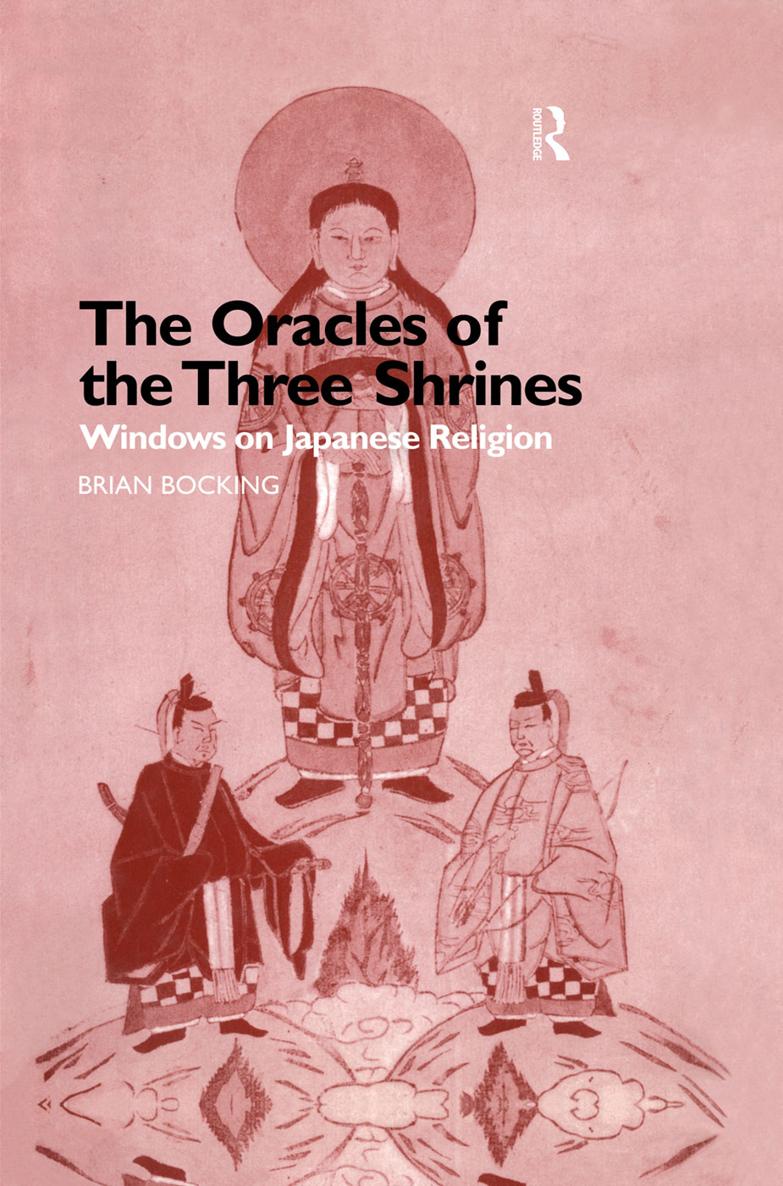

A chance event started me off on the track of The Oracles of the Three Shrines. In 1982 I saw in an antiquarian shop in the city of Kobe an inexpensive scroll which from its appearance seemed at least fifty years old. It showed Amaterasu, the sun goddess and progenitor of the imperial line, attended by a couple of other lesser deities (this scroll is included as ). The scroll evidently had Shinto significance of some kind but I had already imbibed from books about Japanese religions the notion that Shinto was, in contrast to Buddhism, a religion without images or icons. A well-respected reference work on religions published at the time said of Amaterasu that she is not represented in the arts and without any deeper knowledge of my own of Shinto art I could not place the scroll in any larger context of meaning. For me it remained for some years simply a useful curiosity; perhaps a visual expression, I thought, of the hierarchical structure of prewar emperor-centred Shinto, in which the sun goddess, the imperial ancestor, represented the apex of the national hierarchy.

Some years later I was commissioned by Curzon Press to write A Popular Dictionary of Shinto. I took up the challenge not because I felt I knew enough about Shinto to write a dictionary but on the contrary because I hoped that in trying to write a dictionary I might learn something more substantial about Shinto. While following up the term sanja takusen (The Oracles of the Three Shrines) from a brief entry in the Jinja Honchos booklet Basic Terms of Shinto, I came across Mori Kazues short essay on the subject in an excellent new Japanese .

This was my first sight of what I now call a standard sanja takusen and the resemblance between my relatively modern Kobe scroll showing Amaterasu with two attendant deities and the much older sanja takusen was immediately obvious. Each has the names of the same three shrine-deities at the top of the scroll (Amaterasu or Ise in the centre, Hachiman and Kasuga on the left and right hand of Amaterasu respectively) and three sections of Chinese text below. However, with the exception of the three names and their relative positions at the head of the scroll, the Kobe and Kokuguin scrolls are in fact very different from each other. The Kobe scroll has pictures of the personified deities as well as texts, while on closer inspection the texts in the more modern scroll (which are drawn from the eighth century Nihongi) are unrelated to the texts found in the Kokugakuin version. The honorific titles attached to the names of the shrine-deities at the head of the scroll are different too. The Kobe scroll has Great Imperial Kami Amaterasu, Great Kami Hachiman and Great Kami Kasuga while the Kokugakuin scroll has simply Ise, Hachiman and Kasuga. Evidently, the style and contents of the Kokugakuin scroll had over course of time somehow evolved into the much more recent Kobe scroll. If so, then the stages in the evolution of the scroll might be traceable, if only one could discover the intervening and perhaps even earlier and later examples. The rest, one might say, is this history.

I am profoundly grateful to all of the institutions and individuals who have allowed me to reproduce images in this book. Copyright details are shown with each illustration.

The initial fieldwork research for this book, carried out in Japan during November-December 1996, was funded by The Humanities Research Board of the British Academy and the Research Committee of Bath Spa University College. A period of sabbatical leave from February 1999 to January 2000 funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Board enabled me to collect further data, consult relevant literature, pursue the many necessary copyright clearances from Japan for the images reproduced in the following pages, translate the Sanja takusen ryakush and generally write this book. I am truly grateful to my colleagues in the Study of Religions department at Bath Spa University College who covered for my absence from February to August 1999, and to SOAS (the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London) for honouring the original terms of my AHRB award to allow me to continue this work from September 1999, when I formally joined the Department of the Study of Religions at SOAS, until January 2000.

Since I first started enquiring about the sanja takusen I have been helped along the way by information, ideas and suggestions from many colleagues and acquaintances in Japan and elsewhere. Needless to say, all errors and omissions remain my own responsibility. I cannot list here the name of everyone to whom I have spoken about the sanja takusen but the following deserve my special thanks for expert help and advice at different points. In the UK: Carmen Blacker; Yu-Ying Brown, Sam Fogg, Hiroko Kawanami, Meher McArthur, Takeuchi Nobuyuki of Tenrikyo UK, Michiko Sugino, Mark Teeuwen (now in Oslo); Hamish Todd, and my SOAS colleagues Tim Barrett, John Breen, Lucia Dolce, Gaynor Sekimori and Youxuan Wang. In Kyoto: Rev. Takano Asami of the Yoshida Shrine, Mrs Yokoyama Aoi, Mr Maezawa Eiichi of Seikan-do Maezawa Co., Ltd, Mrs Kano of Sanshibo, Prof. Sonoda Minoru of Kyoto University, Rev. Takeuchi Mitsuyoshi of the Kamo shrine. In Tokyo: Ms Chida Kazue, staff of the Jinja Honcho, Ms Matsui Kaoru and Mr Tsuboyama Masatoshi of the Edo-Tokyo Museum. Mr Hitomi Tsuyoshi, Prof. Mitsuhashi Takeshi, Prof. Mogi Sakae, Prof. Shimada and Prof. Sugiyama Shigetsugu and other staff of Kokugakuin University and Prof. Isogai Yukihiko of Kokugakuin University Library. Prof. Shimazono Susumu of Tokyo University and other friends from Tsukuba days. Staff of the Tokugawa Reimeikai Foundation. In Nagoya: Rev. Handa Shigeru of the Ueno Tenmang, Mr Koike Tomio of the Tokugawa Art Museum, Paul Swanson and James Heisig of Nanzan University. At Hasedera: Rev. Mineyama Kyo and Rev. Abe Yuk. In Ise: Prof. Sakurai Haruo and Mr Motozawa Masafumi of Kogakkan University; Mr Yoshikawa Tatsumi and Ms Honda Hisako of Jing Chkokan. Staff of Sugiyama Kakejikuten. In Oita: Prof Matsushita Hidetaka and Mrs Matsushita Sayoko, Ms no Amako of Gyaruria ra paretto. In Tenri: Mr Iida Teruaki and Mr Miyajima Ichir of Tenri University Library, Mr nishi Yoshinori of Tenrikyo. In Nara: Mr higashi, Ms Matsumura Wakako and staff of the Kasuga Taisha, Prof. Shunp Horiike and staff of the Todaiji library. To anyone whom I have inadvertently omitted from this list I tender my sincere apologies.