THE KAMI WAY

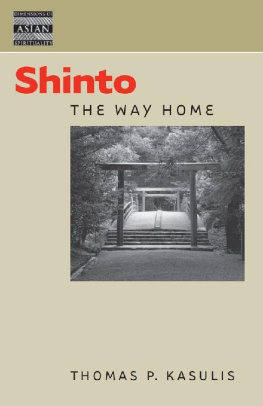

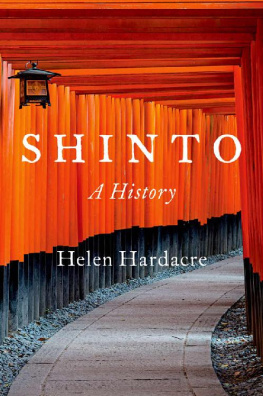

S hinto, the indigenous faith of the Japanese people, is relatively unknown among the religions of the world. Many people are familiar with the torii , the typical gateway to Shinto shrines, and some have a vague impression of the unique ornamentation which adorns many shrine roofs. Yet to all but a few, the shrines to which the torii leads and the Shinto faith which it symbolizes are very much of an enigma.

Introduction

From time immemorial the Japanese people have believed in and worshipped kami as an expression of their native racial faith which arose in the mystic days of remote antiquity. To be sure, foreign influences are evident. This kami-faith cannot be fully understood without some reference to them. Yet it is as indigenous as the people that brought the Japanese nation into existence and ushered in its new civilization; and like that civilization, the kami-faith has progressively developed throughout the centuries and still continues to do so in modern times.

The word Shint ("Chronicles of Japan,") which was published early in the eighth century. There it was newly employed for the purpose of distinguishing the traditional faith of the people from Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism, the continental ways of thinking and believing, which in recent centuries had entered the land. There is no evidence, however, that the term in the sense in which it appears in the Nihon Shoki was in general use at that time, either among the people as a whole or among scholars.

Shint is composed of two ideographs  ( shin ), which is equated with the indigenous term kami , and

( shin ), which is equated with the indigenous term kami , and  . (d or t), which is equated with the term michi, meaning "way." Originally Chinese ( Shntao

. (d or t), which is equated with the term michi, meaning "way." Originally Chinese ( Shntao  ) in a Confucian context it was used both in the sense of the mystic rules of nature, and to refer to any path leading to a grave. In a Taoist setting, it meant the magical powers peculiar to that faith. In Chinese Buddhist writings there is one instance where Gautama's teachings are called

) in a Confucian context it was used both in the sense of the mystic rules of nature, and to refer to any path leading to a grave. In a Taoist setting, it meant the magical powers peculiar to that faith. In Chinese Buddhist writings there is one instance where Gautama's teachings are called  and another in which the term refers to the concept of the mystic soul. Buddhism in Japan used the word most popularly, however, in the sense of native deities (kami) or the realm of the kami, in which case it meant ghostly beings of a lower order than buddhas ( hotoke ). It is generally in this sense that the word was used in Japanese literature subsequent to the Nihon Shoki; but about the 13th century, in order to distinguish between it and Buddhism and Confucianism, which had by that time spread throughout the country, the kami-faith was commonly referred to as Shint, a usage which continues to this day.

and another in which the term refers to the concept of the mystic soul. Buddhism in Japan used the word most popularly, however, in the sense of native deities (kami) or the realm of the kami, in which case it meant ghostly beings of a lower order than buddhas ( hotoke ). It is generally in this sense that the word was used in Japanese literature subsequent to the Nihon Shoki; but about the 13th century, in order to distinguish between it and Buddhism and Confucianism, which had by that time spread throughout the country, the kami-faith was commonly referred to as Shint, a usage which continues to this day.

Unlike Buddhism, Christianity, and Islam, Shinto has neither a founder, such as Gautama the Enlightened One, Jesus the Messiah, or Mohammed the Prophet; nor does it have sacred scriptures, such as the sutras of Buddhism, the Bible, or the Qur'an (Koran).

In its personal aspects "Shinto" implies faith in the kami, usages practiced in accordance with the mind of the kami, and spiritual life attained through the worship of and in communion with the kami. To those who worship kami, "Shinto" is a collective noun denoting all faiths. It is an all-inclusive term embracing the various faiths which are comprehended in the kami-idea. Its usage by Shintoists, therefore, differs from calling Buddha's teaching "Buddhism" and Christ's teaching "Christianity."

In its general aspects Shinto is more than a religious faith. It is an amalgam of attitudes, ideas, and ways of doing things that through two millenniums and more have become an integral part of the way of the Japanese people. Thus, Shinto is both a personal faith in the kami and a communal way of life according to the mind of the kami, which emerged in the course of the centuries as various ethnic and cultural influences, both indigenous and foreign, were fused, and the country attained unity under the Imperial Family.

Mythology

The Age of the Kami, the mythological age, sets the Shinto pattern for daily life and worship. In the mythology the names and order of appearance of the kami differ with the various records. According to the Kojiki the Kami of the Center of Heaven (Ame-no-minaka-nushi-no-kami) appeared first and then the kami of birth and growth (Taka-mimusubi-no-mikoto and Kami-musubi-no-mikoto). However, it is not until the creative couple, Izanagi-no-mikoto and Izanami-no-mikoto, appear that the mythology really begins. These two, descending from the High Plain of Heaven, gave birth to the Great Eight Islands, that is, Japan, and all things, including many kami. Three of the kami were the most august: the Sun Goddess (Ama-terasu--mikami), the kami of the High Plain of Heaven; her brother (Susa-no-o-no-mikoto), who was in charge of the earth; and the Moon Goddess, (Tsuki-yomi-no-mikoto), who was the kami of the realm of darkness.

The brother, however, according to the Kojiki behaved so very badly and committed so many outrages that the Sun Goddess became angry and hid herself in a celestial cave, which caused the heavens and earth to become darkened. Astonished at this turn of events, the heavenly kami put on an entertainment, including dancing, which brought her out of the cave; and thus light returned to the world. For his misdemeanor the brother was banished to the lower world, where by his good behavior he returned to the favor of the other kami, and a descendant of his, the Kami of Izumo (kuni-nushi-no-kami), became a very benevolent kami, who ruled over the Great Eight Islands and blessed the people. Little is said in the mythology of the Moon Kami.

Subsequently, the grandson of the Sun Goddess, Ninigi-no-mikoto, received instructions to descend and rule Japan. To symbolize his authority he was given three divine treasures: a mirror, a sword, and a string of jewels. Moreover, he was accompanied on his journey by the kami that had participated in the entertainment outside the celestial cave. However, to accomplish his mission it was necessary to negotiate with the Kami of Izumo, who after some discussion agreed to hand over the visible world, while retaining the invisible. At the same time, the Kami of Izumo pledged to protect the heavenly grandson. Ninigi-no-mikoto's great grandson, Emperor Jimmu, became the first human ruler of Japan.

This, in very simple form, is the basic myth which explained for primitive Japanese their origin and the basis of their social structure. It is a description of the evolution of Japanese thought in regard to the origin of life, the birth of the kami and all things out of chaos, the differentiation of all phenomena, and the emergence and evolution of order and harmony. In a sense, the myth amounts to something like a simple constitution for the country. However, in the ancient records the account is not uniform. There are several versions of a number of events, some of which are contradictory. Thus, the traditions of the various clans were preserved and to a certain extent recognized as valid.

Shinto recognizes today that its beliefs are a continuation of those of this mythological age. In its ritual forms and paraphernalia, this faith fully retains much that is ancient. But just as the Grand Shrine of Ise, which aims at preserving the oldest style of buildings and ancient rituals, has created the most beautiful architectural style in the country today, so Shrine Shinto has outgrown much of its historic mythology. The buds of truth have appeared and have been refined for the people of modern Japan.

( shin ), which is equated with the indigenous term kami , and

( shin ), which is equated with the indigenous term kami , and  . (d or t), which is equated with the term michi, meaning "way." Originally Chinese ( Shntao

. (d or t), which is equated with the term michi, meaning "way." Originally Chinese ( Shntao  ) in a Confucian context it was used both in the sense of the mystic rules of nature, and to refer to any path leading to a grave. In a Taoist setting, it meant the magical powers peculiar to that faith. In Chinese Buddhist writings there is one instance where Gautama's teachings are called

) in a Confucian context it was used both in the sense of the mystic rules of nature, and to refer to any path leading to a grave. In a Taoist setting, it meant the magical powers peculiar to that faith. In Chinese Buddhist writings there is one instance where Gautama's teachings are called  and another in which the term refers to the concept of the mystic soul. Buddhism in Japan used the word most popularly, however, in the sense of native deities (kami) or the realm of the kami, in which case it meant ghostly beings of a lower order than buddhas ( hotoke ). It is generally in this sense that the word was used in Japanese literature subsequent to the Nihon Shoki; but about the 13th century, in order to distinguish between it and Buddhism and Confucianism, which had by that time spread throughout the country, the kami-faith was commonly referred to as Shint, a usage which continues to this day.

and another in which the term refers to the concept of the mystic soul. Buddhism in Japan used the word most popularly, however, in the sense of native deities (kami) or the realm of the kami, in which case it meant ghostly beings of a lower order than buddhas ( hotoke ). It is generally in this sense that the word was used in Japanese literature subsequent to the Nihon Shoki; but about the 13th century, in order to distinguish between it and Buddhism and Confucianism, which had by that time spread throughout the country, the kami-faith was commonly referred to as Shint, a usage which continues to this day.