Published in Great Britain by

Simple Guides, an imprint of Bravo Ltd

59 Hutton Grove, London N12 8DS

www.kuperard.co.uk

Enquiries:

First published 1998 by Global Books Ltd.

Reprinted 2001

This edition published 2007

Copyright 2007 Bravo Ltd.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission in writing from the Publishers

eISBN: 978-1-85733-631-3

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A CIP catalogue entry for this book

is available from the British Library

Cover image: Torii (shrine gateway) in the Japanese Gardens,

Birmingham, Alabama. istockphoto/Philip Dyer

Drawings by Irene Sanderson

v3.1

About the Author

IAN READER has been teaching and researching on the religions of Japan for many years. His PhD on Japanese Buddhism was gained at the University of Leeds in 1983, after which he and his wife Dorothy lived and worked in Japan for almost six years. Since 1989 he has been a member of the Scottish Centre for Japanese Studies at the University of Stirling, Scotland. He also spent a year as a Visiting Professor at the University of Hawaii in 199293. For three years from August 1995 he lived in Copenhagen, Denmark, where he was a Senior Research Fellow at the Nordic Institute of Asian Studies.

Amongst his books are Religion in Contemporary Japan (Macmillan, 1991); Pilgrimage in Popular Culture (edited with Tony Walter, Macmillan, 1993) and A Poisonous Cocktail? Aum Shinrikys Path to Violence (NIAS Books, Copenhagen 1996).

For Norman and Joan Taylor, my parents-in-law.

Contents

List of Illustrations

Shinto gateway (torii) at Shiroyama shrine, Nagoya

The Seven Gods of Good Fortune

Yasaka shrine, Kyoto

Amaterasu emerging from her cave

Kasuga shrine, Nara

Sacred tree with ropes (shimenawa) and paper strips (gohei)

Shinto priests with mace (shaku)

Parading the local shrine (omikoshi)

Offerings to the kami

Statue of sacred horse with ema

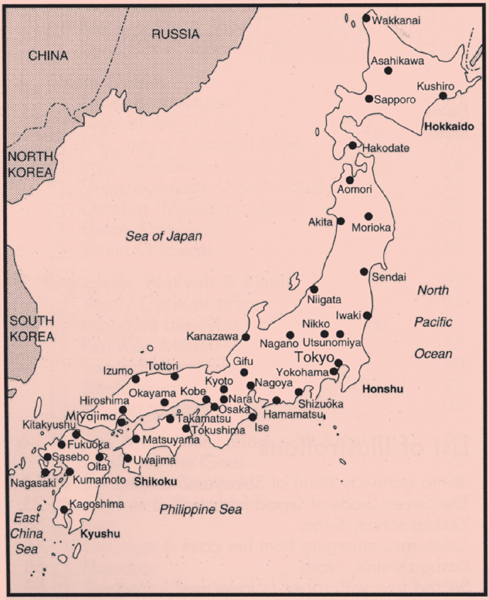

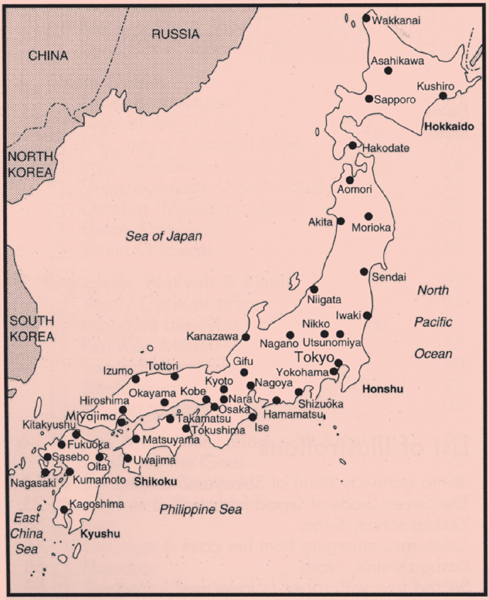

Map of Japan

Preface

The word Shinto is a Japanese term which translates as the way of the gods, and refers to a religious tradition associated with the land and people of Japan. Shinto is a prominent element in that countrys religious and physical landscape, with Shinto shrines being highly visible, whether in the main cities or in the mountains and countryside.

Japanese shops and small family businesses also may have their own shrines for the gods of business prosperity, as may Japanese factories and modern commercial enterprises as well. Japanese houses, too, may contain Shinto symbols of worship in the form of the kamidana, or Shinto household altar, that enshrines the households protective deities.

The deities of Shinto may be called into action on many occasions throughout life, from life-cycle rituals to calendrical events, from the blessings given to newly-born babies at Shinto shrines a form of first entry into society to annual community festivals and celebratory events.

Shinto also expresses, through its myths and legends, various teachings and meanings concerned with issues of purity and correct behaviour, with attitudes to life and death, with the relationship between humans and deities, with the nature of the world, and of the life-forces that, according to Shinto, permeate it in the form of its gods, and with the roles and responsibilites of those gods in this world.

Shinto myths also assert that a special relationship exists between the people and landscape of Japan and the deities of Shinto, who serve as guardians and protectors of the country. This concept was expressed nowhere more famously than in the late thirteenth century, when Japan was threatened by invasion from the Mongol forces that had occupied China and were preparing a military assault on Japan, first in 1274 and then again in 1281. The Japanese Imperial court called for prayers to be said throughout the country, to seek divine protection against this threat.

When the ships bearing the invading Mongol armies were destroyed as a result of bad weather thereby averting the only major threat to Japans sovereignty until it was occupied by Allied forces after its defeat in 1945 it was believed that the prayers of the nation had been answered by the gods, who had thus sent divine winds the literal meaning of the Japanese word kamikaze for this purpose.

Mention of the term kamikaze conjures up darker images as well, alluding to Shintos controversial association with Japanese nationalism and the role it played in the earlier part of the twentieth century in supporting the Imperial Japanese state during its period of militant expansion and war. It was in the name of the Emperor depicted in pre-war Japan as a Shinto deity, a depiction based in Shinto myths of Imperial descent from the gods that the kamikaze pilots flew their missions, and it was through the medium of Shinto that the Emperor was transformed into a figure of veneration in whose name wars were fought and the enemies of the state were suppressed.

This use of Shinto as a religion of state associated with the suppression of religious freedoms, and of aggressive nationalism, was a factor leading to the imposition on Japan of the post-war Constitution which separates religion and state and prohibits state support of religion an issue which itself is a source of lingering controversy in the present day.

All these issues will be dealt with in this book, the aim of which is to explain what the religious tradition of Shinto means in terms of Japanese history and contemporary society, and to describe its meanings and myths, the teachings these embody, and the practices, rituals and festivals of Shinto. The earlier chapters will discuss what is meant by the term Shinto, and give an outline of its history, placing it within the broader context of Japanese religion. Shinto is, however, as has been noted above, a very visible presence in Japan which will be discussed later in the book when we consider Shinto in the present day, outlining the sorts of practices, rituals and festivals that visitors are likely to see if they go to Shinto shrines.

Thus, we will discover what Shinto shrines look like, what one is liable to see going on there, and what the various objects such as amulets and lucky charms that are sold at shrines mean, and why Japanese people purchase them. It will also introduce some important Shinto shrines and will draw attention to the visual spectacle and the publicly viewed phenomena of Shinto, from its wild and colourful festivals to its sedate rituals. However, just as the controversies associated with Shinto remain an ever-present element in the contemporary Japanese religious world so, too, will they be discussed here as well, with a chapter examining the problematic relationship of Shinto and the state and the issues this involves in the present day.

The materials on which I draw for this book range from historical documents and the academic writings of other scholars, to my own observations at countless Shinto shrines, festivals and ritual events over the past seventeen years since I first visited Japan in 1981. For a number of years in the 1980s my wife Dorothy and I lived and taught there, and during that period we visited many Shinto shrines, talked to Shinto priests, shrine maidens and practitioners, from the casual visitors to Shinto festivals, to those who visit their local shrines regularly to pray to the gods.