Bibliography

INTRODUCTION

Shinto has been the subject of more serious attention in the last decade of the 20th century than it has been in the entire period since Japan first began to open its doors to the West in the mid-19th century. Nevertheless, there remains a dearth of materials in English in particular and in Western languages in general. Most of what exists derives from and is colored by the agenda of the Meiji period (18681912). Shintos first encounters with the West were taking place at a time when the Japanese government was seeking to create, in the interests of modernization, a national religion that would serve simultaneously as a national ideology. Hence the image of Shinto that emerged toward the end of the 19th century was that of a religion that consisted of little more than a sterile system of rituals with virtually no spiritual vitality.

Anyone visiting a present-day shrine festival will immediately testify to the inaccuracy of this view. However, images linger, and there is public perception of Shinto as a government-initiated structure focusing on the war dead, the Yasukuni Shrine and the emperor system did much to damage the image as well as the true reality. Shinto itself has undergone a post-World War II revival, largely due to the religious freedom policy put into effect in 1945, because of which much of the ancient spirituality has been regenerated. New movements have emerged and old shrines have come back to life. Consequently, while the bibliography was compiled on strictly academic lines, it became necessary nevertheless to include some popular writings that will bring readers closer to the realities of 21st century Shinto. This is supplemented by some general studies of Japanese culture that in different ways have a bearing upon Shinto.

Among the more recent insightful and enlightening writings that begin to draw attention to aspects of Shinto are the works of Professor Allan G. Grapard, in particular his excellent work The Protocol of the Gods: A Study of the Kasuga Cult in Japanese History , 1992. There is also John K. Nelsons book on the life of the Suwa Jinja ( A Year in the Life of a Shinto Shrine , 1996) and Mark Teeuwens discussion of Watarai Shinto ( An Intellectual History of the Outer Shrine of Ise , 2000). Each makes a sizeable contribution to the understanding of an area of Shinto that helps to display the richness and complexity behind its physical presence as well as its various traditions.

The listings close with some websites that might be helpful for those who wish to pursue more empirical lines of inquiry. Perhaps their inclusion should be qualified by a few remarks. Firstly, anyone who has ever used the Internet for research will realize exactly how imperfect, unbalanced, and frequently misleading it can be. Sites may vary in quality, from those designed for official public relations purposes, intended to convey as much accurate information as possible, to those created by well-meaning but either unqualified or incompetent amateurs, analogous to the difference between a well-made documentary and a badly made home video. Shinto websites are no exception. Some are official, some are parts of course materials for academic programs, and some are subjective flights of fantasy. Such is the Internet. For those requiring visual images, there are numerous sites that offer video clips and other relevant materials. I have listed only sites that I believe to be reliable, including some because they provide links to other sites; however, no one can guarantee that the links are all of the same quality. In the case of Shinto, sound reading and actualrather than virtualcontact will always be the measure against which theory and web images must be judged.

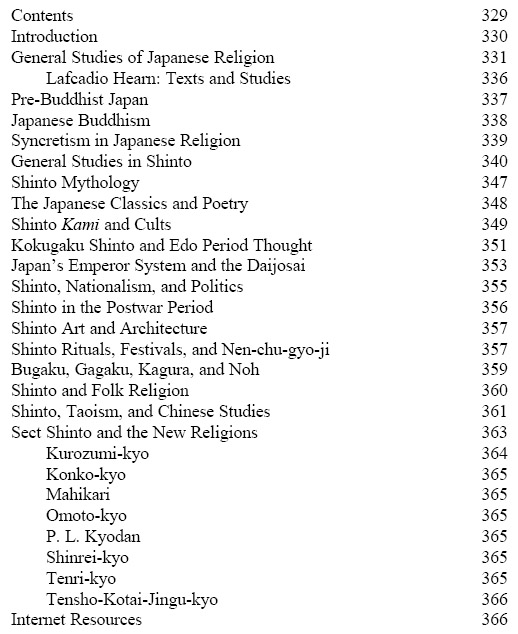

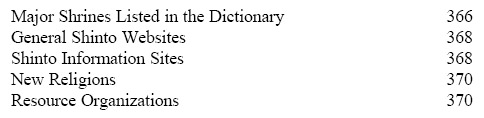

The headings used to categorize the listings were created to assist those who might be looking for materials under a particular theme. Many titles might have been justifiably placed in more than one category, but to do so would have made the bibliography extremely cumbersome. Those used are not the only ones possible, but are probably the most helpful for general study purposes.

GENERAL STUDIES OF JAPANESE RELIGION

Anesaki Masaharu. History of Japanese Religion. London: Kegan Paul, 1930.

. Art, Life and Nature in Japan. Boston: Marshall Jones Company, 1932.

. Religious Life of the Japanese People. Tokyo: Japan Cultural Society, 1970.

Armstrong, Robert C. Just before the Dawn: The Life and Work of Ninomiya Sontoku . New York: Macmillan, 1912.

Ashida K. Japan. In Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics . Edited by James Hastings. Vol VII: 481489. Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1914.

Bellah, Robert. Tokugawa Religion. Glencoe, IL: Free Press, 1957.

Bernard-Maitre, Henri. LOrientaliste Guillaume Postel et al decouverte spirituelle du Japon en 1552. Monumenta Nipponica 9 (1954): 83108.

Borgen, Robert. Sugawara no Miichizane: Ninth-Century Japanese Court Scholar, Poet and Statesman. Ph.D. dissertation. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 1978.

Brumbaugh, T. T. Religious Values in Japanese Culture . Tokyo: Kyo Bun Kwan, 1934.

Bunce, William. Religions in Japan , Ch. 68. Tokyo: Tuttle, 1973.

Chamberlain, Basil Hall. Classical Poetry of the Japanese. London: Trubner, 1880.

. The Language of Mythology, and Geographical Nomenclature of Japan Viewed in the Light of Aino Studies . Tokyo: Tokyo Imperial University, 1887.

. Things Japanese. London: K. Pul, Trench, Trubner & C., 1905.

Cousins, Steve. Culture and Self Perception in Japan and the United States. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 56, no. 1 (1989): 124131.

Davis, W. Pilgrimage and World Renewal: A Study of Religion and Social Values in Tokugawa Japan, Part I. History of Religions 23, no. 1 (November 1983).

. Pilgrimage and World Renewal: A Study of Religion and Social Values in Tokugawa Japan, Part II. History of Religions 23, no. 3 (February 1984).

. Japanese Religion and Society: Paradigms of Structural Change . Albany: State University of New York Press, 1992.

Earhart, H. Byron. Japanese Religion: Unity and Diversity . Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 1974.

. Religion in the Japanese Experience: Sources and Interpretations. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 1974.

Elison, George, and Bardwell L. Smith, eds. Warlords, Artists & Commoners: Japan in the Sixteenth Century . Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1981.

Fisher, Jerry T. Nakamura Keiu: The Evangelical Ethic in Asia. In Religious Ferment in Asia . Edited by Robert J. Miller. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1974.

Fridell, Wilbur M. Notes on Japanese Tolerance. Monumenta Nipponica 27 (1972): 253271.

. Thoughts on Man and Nature in Japan: A Personal Statement. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 5/23 (JuneSeptember 1978): 186190.

Griffis, William Elliot. The Religions of Japan: From the Dawn of History to the Era of Meiji. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1901.

Hall, John Whitney, Nagahara Keiji, and Yamamura Kozo, eds. Japan Before Tokugawa: Political Consolidation and Economic Growth, 15001650. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1981.

Hase Akihasa. Japans Modern Culture and its Roots . Tokyo: International Society for Educational Information, 1982.

Havens, T. R. H. Religion and Agriculture in Nineteenth-Century Japan: Ninomiya Sontoku and the Hotoku Movement. Japan Christian Quarterly 38, no. 2 (1972).

. Farm and Nation in Modern Japan : Agrarian Nationalism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1974.