APPENDIX

By George L. Trager, Yale University

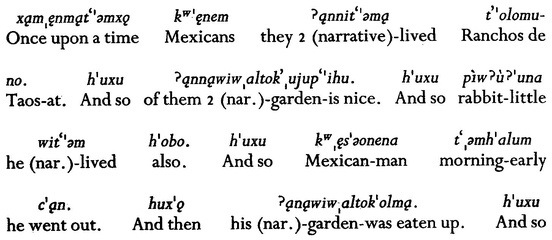

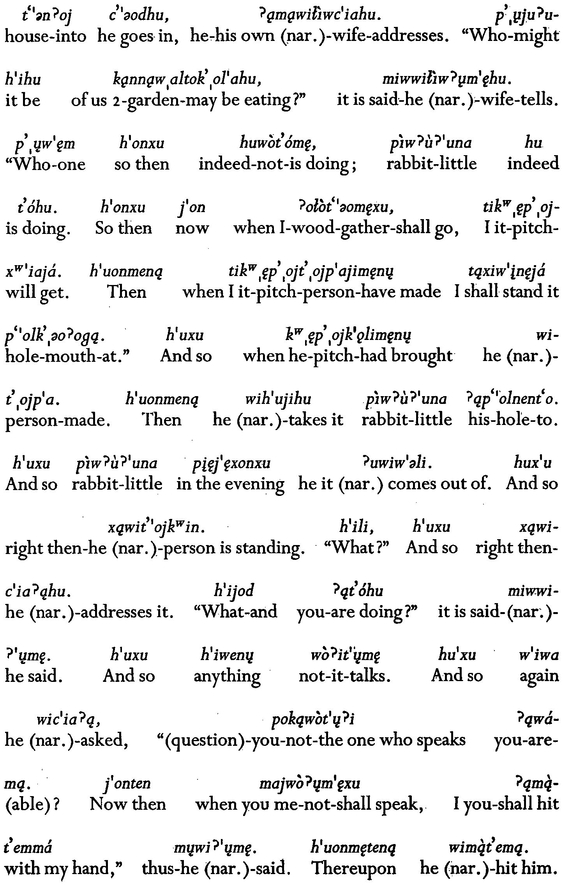

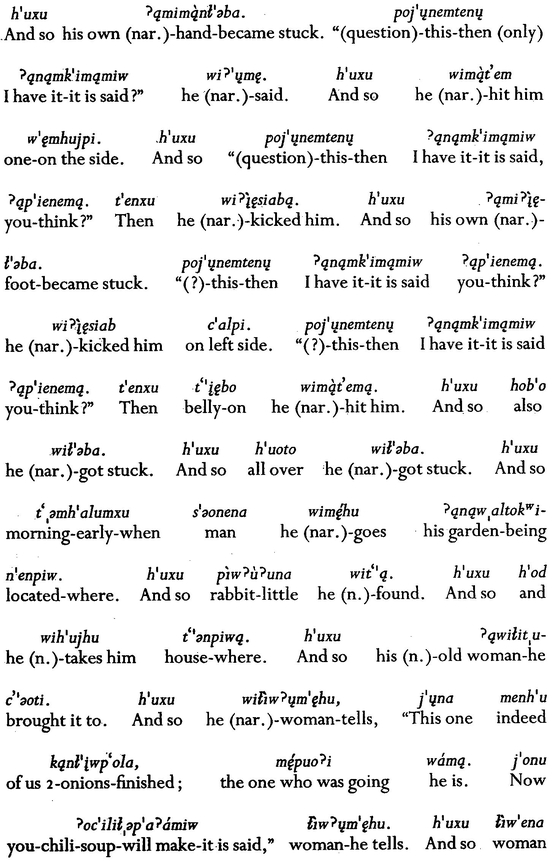

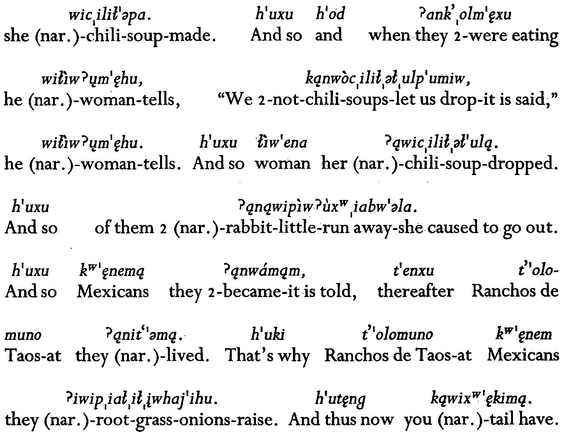

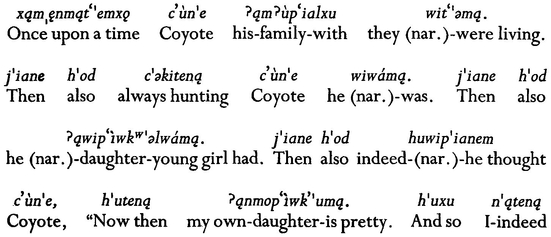

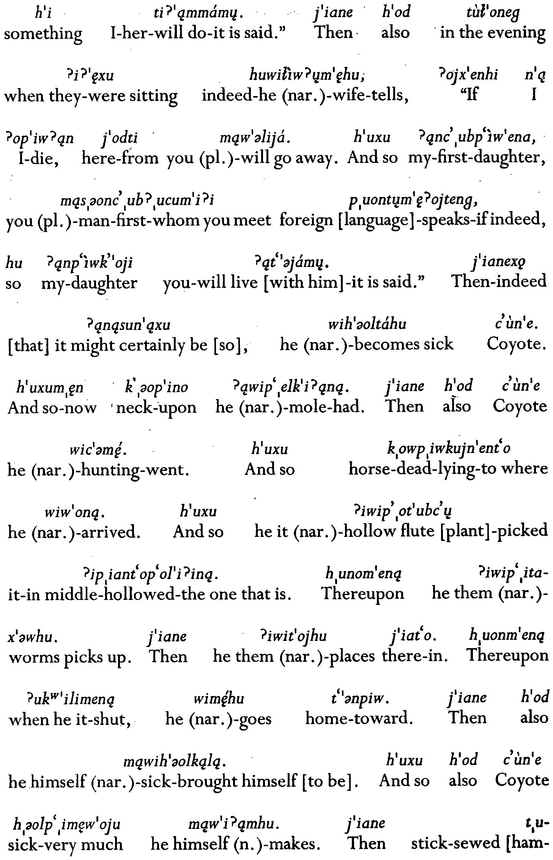

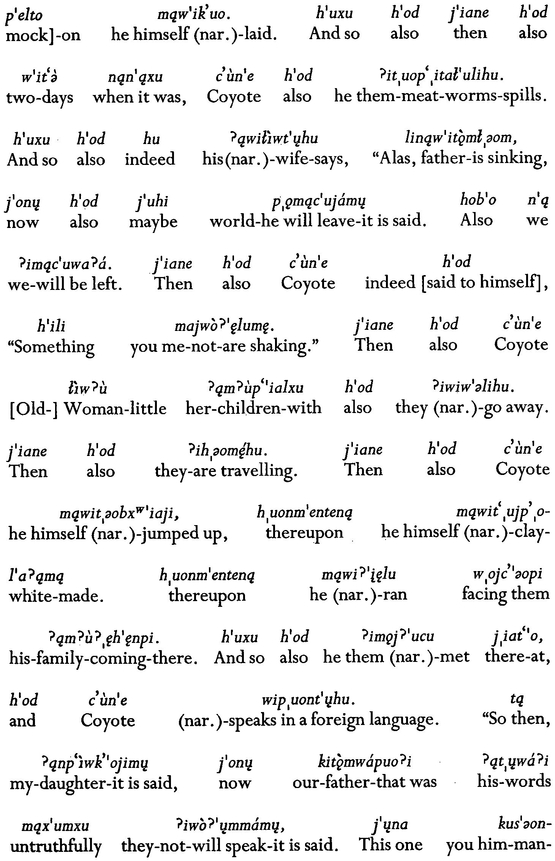

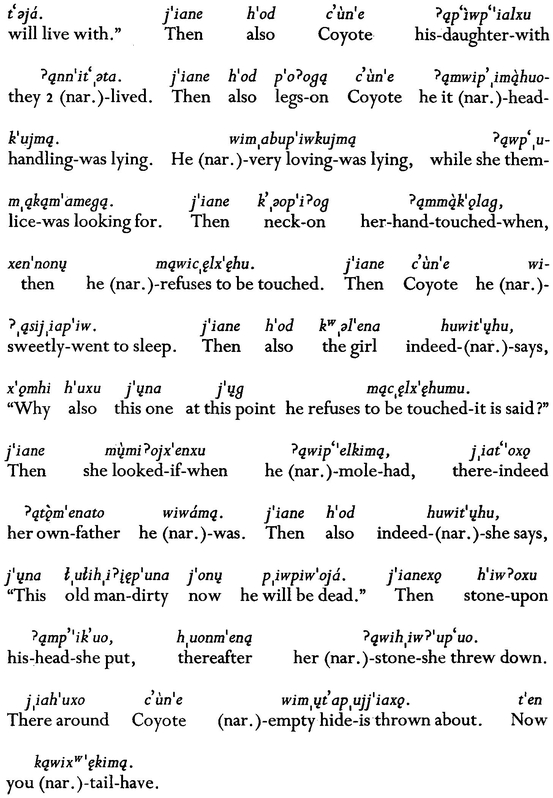

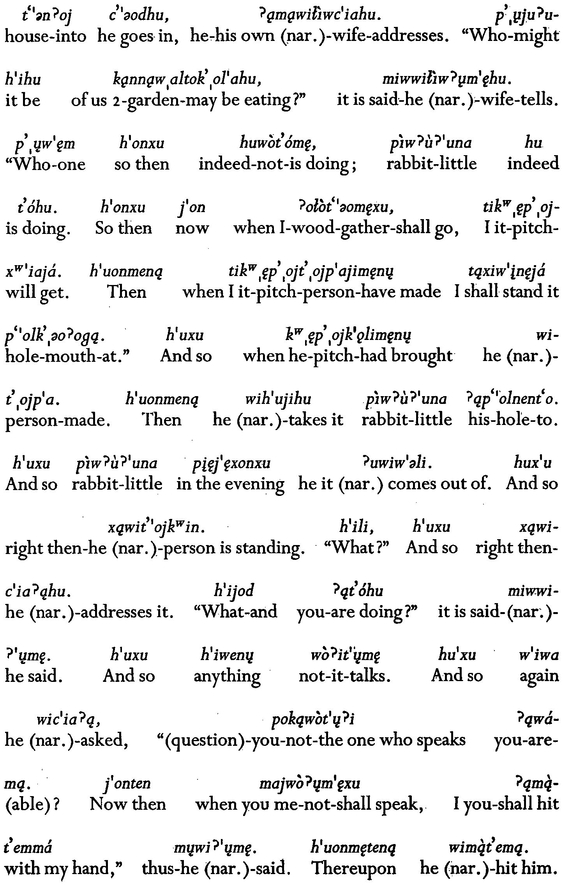

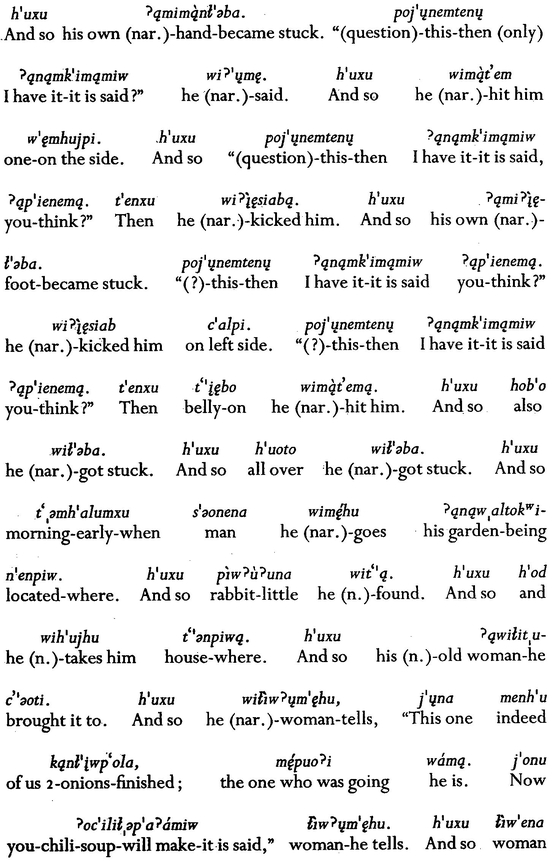

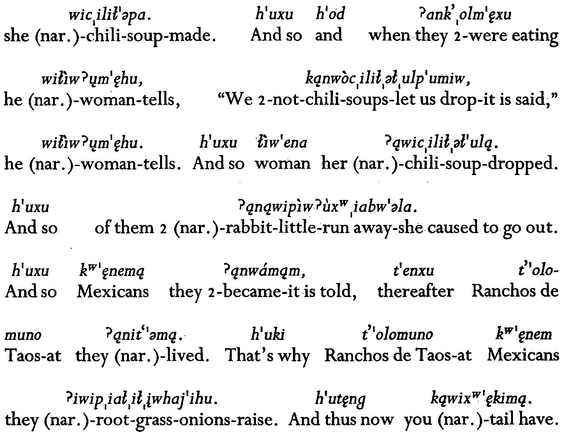

The following tales are given as they were recorded, except that occasional phonetic notations have been replaced by the final phonemic analysis; normalizations have been introduced only in a few cases of evident error, but many of the accentual indications have been supplied after recording; words appear with the accentual forms they have in isolation except in those cases where these have been changed by sentence sandhi. Commas in the text indicate non-terminal pauses, and periods the terminal pauses; these are the only two sentence types known to me for Taos.

For phonological and grammatical details reference must be made to my Outline of Taos Grammar, in a volume whose collection was begun by Edward Sapir and is now being edited by Professor L. Bloomfield. In line with the practise of that Outline, the symbol j is used here for the palatal semivowel (rendered by y in the rest of the present volume), and initial glottal stop is written instead of being omitted.

The interlinear translation is literal, but does not always render exactly the order of elements in a Taos word; hyphens are used between elements.

Free translation

Once upon a time two Mexicans lived at Ranchos de Taos. They had a nice garden. A little rabbit lived there also. Early one morning the Mexican man went out and found his garden all eaten up. So he went into the house and said to his wife, Who might it be that is eating up our garden? No person is doing it, the little rabbit is doing it. So when I go to gather wood I shall get some pinyon gum pitch. Then when I have made a pitch- [figure like a] man, I shall stand it at the mouth of the [rabbits] hole. And when he had brought the pitch he made a figure and took it to the little rabbits hole. And the little rabbit came out in the evening and there was the figure standing. Whats this? he said, and addressed it: What are you doing here? But it didnt answer anything. So he asked again, Arent you able to speak? If you dont speak to me, Ill hit you. Then he hit it and his hand became stuck. Do [you think] I have only this one?, he said, and hit it on the other side. And then he said, Do you think I have only this one? Then he kicked it and his foot became stuck. Do you think I have only this one? And he kicked it on the left side. Do you think I have only this one? Arid he hit it with his belly. And this also got stuck. And so he was stuck all over. And early the next morning the man went to his garden and found the little rabbit. And he took him home and brought him to his old woman and said to her, This is the one who destroyed our onions and who was running about in our garden. Now make some chili stew with him. And so the old woman made some chili stew. And when they were eating, he told the woman, We mustnt spill any of our chili. But the woman spilled some, and thereby caused their little rabbit to jump out and run away. And so the two of them were Mexicans thereafter; they lived at Ranchos de Taos. And now you have the [fox-]tail [and its your turn].

Coyote tricks his daughter

Free translation

Once upon a time Coyote was living with his family; he was always hunting. He had an adolescent daughter. Coyote thought, My daughter is pretty; so Ill play a trick on her. That evening when they were sitting, he said to his wife, If I die, go away from here; and as for my daughter, the first man whom you meet, if he speaks a foreign language, you will marry him. And so that it might happen in this way, Coyote made himself sick. Now he had a mole on his neck. So Coyote went hunting, and came to a place where a dead horse was lying; and he picked up a hollow-stemmed plant that grew there and gathered some maggots and put them in the hollow. Then he shut it and went home. Then he made believe he was ill, and he looked very ill. Then he lay down on the hammock, and after two days he released the maggots. Then his wife says, Father is sinking, maybe he is leaving the world and us. Then Coyote said to himself, You are no longer shaking me. Then Coyote-Woman goes away with her children, and they are travelling. Then Coyote jumped up, covered himself with white clay, and ran so as to meet his family. And he met them there, and Coyote spoke in a foreign language. [And the mother spoke:] Now, my daughter, our late fathers words will not be spoken in vain. You will marry this man. Then Coyote and his daughter lived together. Once Coyote was lying with his head on her lap; he was very amorous, while she was looking for lice. Then when her hand touched his neck, he pushed it away. Then Coyote gently went to sleep. Then the girl said, Why does he avoid being touched in this place? When she looked, there was a mole there; it was her own father. Then she said: This dirty old man will die for sure now. She put his head on a stone, and dropped another stone on him. And Coyotes skeleton is scattered all around there. Now you have the tail.

LIST OF REFERENCES

| Benedict | 1. | Ruth Benedict. Tales of the Cochiti Indians. Bulletin 98, Bureau of American Ethnology. 1931. |

| 2. | Zuni Mythology. Columbia University Contributions to Anthropology, XXI. 1935. |

| Boas | 1. | Franz Boas. Tales of Spanish Provenience from Zuni. Journal American Folk-Lore, 35: 62-98. 1922. |

| 2. | Keresan Texts. Publications, American Ethnological Society, vol. VIII, Pt. I, 1928. |

| Boas and Simango | F. Boas and C. K. Simango. Tales and Proverbs of the Vandau of Portuguese South Africa. Journal American Folk-Lore, 35: 151-204. 1922. |

| Cushing | F. H. Cushing. Zuni Folk-Tales. New York and London. 1901. |

| Dorsey | 1. | George A. Dorsey. The Mythology of the Wichita. Carnegie Institute of Washington, Publication No. 21. 1904. |