Preface

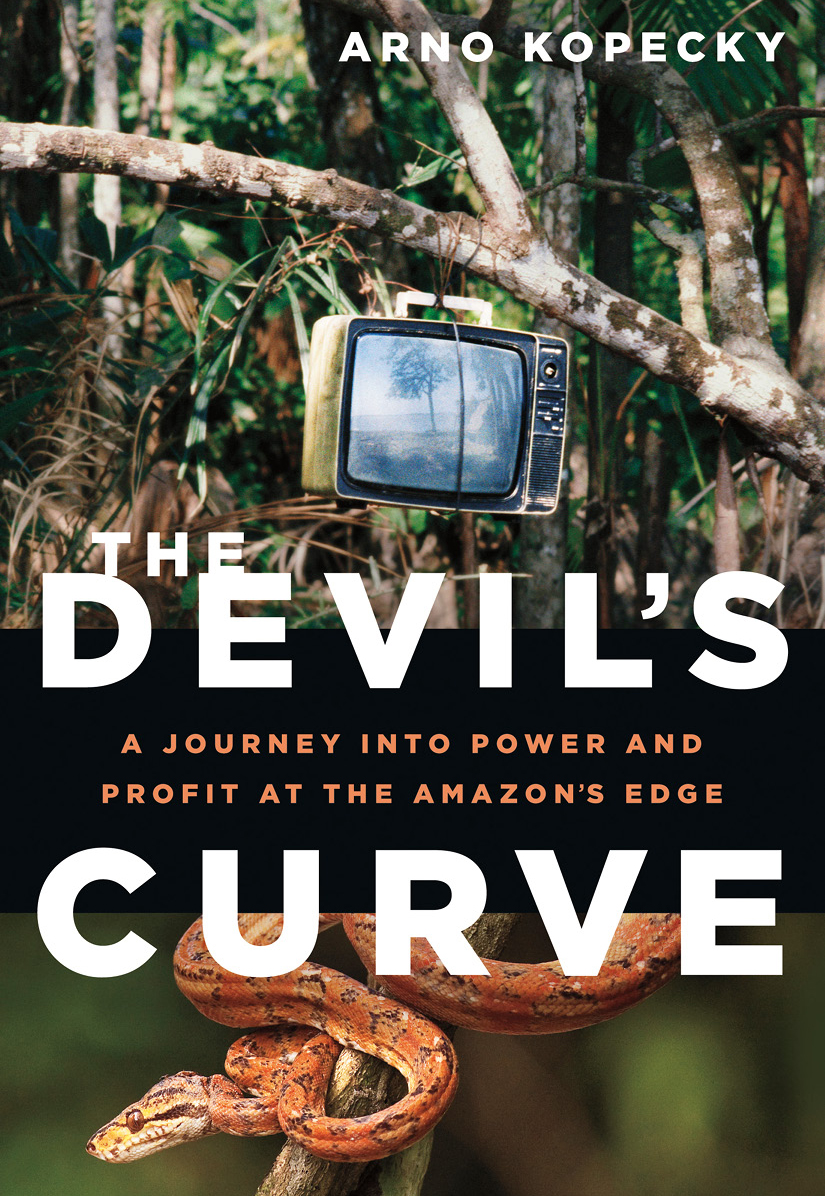

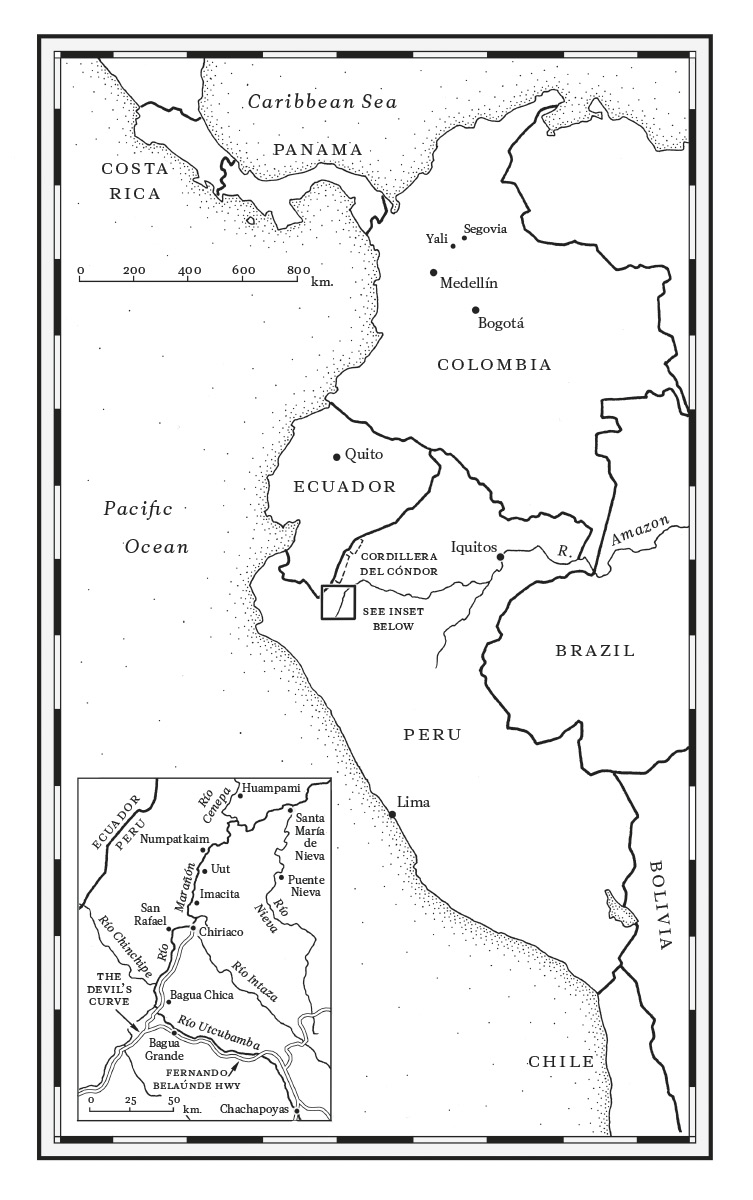

As dawn breaks over the edge of Perus northern Amazon, sixty Peruvian commandos slip into the dry bush above a bend in the highway known as the Curva del Diablo. Three thousand Awajun protesters have been camped on the pavement below for fifty-seven days; to distract their attention from the commandos creeping into position, a second detachment of five hundred soldiers has already gathered on the pavement in plain view of the protesters. Everyone knows somethings coming, but nobody knows what.

The Devils Curve is a mild-seeming twist on the Fernando Belande Highway, the only paved artery between Perus upper rainforest and the Pacific Ocean. By blocking it, the Awajun are costing President Alan Garca a great deal of money, and now they have his attention. They are angry that three-quarters of the jungle, an area the size of France, has been leased to foreign interests in the first decade of this twenty-first century. It isnt just the Awajun who are worried; their blockade is one link, albeit the most vital, of an uprising that has brought almost seventy rainforest tribes together for the first time in history. They have simultaneously shut down river ports, trucking routes, and oil facilities across the entire Peruvian Amazon, grinding industry and commerce to a halt in more than half the country.

A few minutes before six in the morning, the first shot pops off the hilltop. No one on the road can make out where it came from. A second shot soon follows, then several more retorts amid a rising chorus of screams. In response to this invisible commotion, the natives on the highway sway as one; their mass starts to disintegrate as a few step nervously towards the soldiers opposite them, picking up rocks and throwing them heedlessly at the uniformed men. The rocks provoke a lethal response. The soldiers high-calibre semi-automatics sound like cannons, much closer and more visceral than the hilltop cracks, and their instant effect is to send every Indian on the highway diving for the ditch. Those few natives with guns instead of spears now take their first shots. Right around then the helicopter arrives, and for the next two hours the air never stops roaring with gunpowder and tear gas and helicopter rotors, while several thousand Awajun natives in torn jeans and tank tops run and run and run. Eighty-two of them end up in the hospital with bullet wounds, most of them shot in the back.

The whole world saw it happen. On June 4, 2009, one day before the debacle, the army had announced its intention to clear the highway, and although no one expected the operation to be so violently bungled, several local journalists had driven up from Bagua, the closest town, with hand-held video cameras just in case. That mornings shaky footage was broadcast before the sun reached its zenith; the pandemonium was spellbinding. Deadly clashes in Perus Amazon, proclaimed the BBC on June 5. Those killed included at least 22 tribesmen. The New York Times initial story quoted reports of up to twenty-five dead Indians. Al Jazeera reported that at least 60 people, mostly indigenous Indians, died in clashes over land development.

The leaders presiding over each side of the conflict immediately shot from their hips. I denounce this genocide, declared Alberto Pizango, president of the Amazons native coalition, at a hastily organized press conference in Lima. I call it that because they have killed my brothers!

Yes, theres been a genocide, countered Alan Garca, a genocide against the police!

The man had a way with words. Having been run out of the country on corruption charges following his first presidential term, in the 1980s, Garca then sweet-talked his way out of exile (a pampered one, divided between Bogot and Paris) and back into the presidential palace. Hed been a slim thirty-six-year-old socialist the first time he was elected, a brilliant speechmaker known initially as his countrys JFK; but under his watch, hyperinflation topped 7,500 percent, the average Peruvians income dropped 20 percent to $2 a day, and a deadly insurgency calling itself the Shining Path was born. Fifteen years later, inflation was goneso, too, was the Sen-dero Luminoso, and Garca had converted to capitalism. Gone were the socialist speeches and government takeovers of industry that had bankrupted his nation in the eighties; the new Garca understood that only free markets and foreign investors could liberate Peru from destitution.

His approach included a strong measure of unabashed racism, obligingly spelled out in an open letter to Peru that El Comercio, a leading national paper, published in October 2007, setting the tone of political discourse for his next four years in office. Titled The Syndrome of the Dog in the Manger, Garcas essay adapted Aesops fable to his own Amazonian predicament: a jungle full of untapped treasures, blocked by second-class citizens who stubbornly resisted industrial development in their backyard. Many resources arent being traded, invested in, or generating employment, Garca wrote. And all this because of the taboo of outdated ideologies, because of idleness and indolence, or the law of the dog in the manger who says, If I dont eat, no one else eats either.

Garca avoided using the words indigenous or native in his article, but he left no doubt about whom he thought of as dogs and second-class citizens. The timing of his polemic was not accidental. The U.S. and Canada were on the verge of finalizing free trade agreements with Peru, and North American resource extraction companies promised tens of billions of dollars in foreign investmentif only the right laws were in place to protect their interests.

The dog-in-the-manger article helped prepare the ground for those laws. Soon after it came out, Garca won congressional approval to impose a raft of undebated presidential decrees101 in allpassed in the name of complying with the terms of Perus looming free trade agreements. Garcas decretos read like a handbook on how to legalize corporate plunder. They gained instant notoriety, as much for the regal manner by which he inserted them into the constitution as for their debilitating effect on environmental regulations and community rights. Decree 1015, for instance, lowered the proportion of a communitys vote required to sell communal lands (to a mining corporation, say) from two-thirds to one half; Decree 1079 eliminated any laws limiting the central governments power to bring industry into national parks; Decree 1089 created legal procedures to evict people from state-owned land if private investors were interested in the area; and so on, and so forth, times 101.

The decrees exacerbated a centuries-old situation. Once again, natives and campesinos alike watched as their lands were auctioned off for resource profits that flew to regional corporate headquarters in Lima. Perus oligarchy diverted what it could from a white-hot stock exchange that shipped those profits on to New York, Madrid, Rio, Beijing, Toronto. The final scraps drifted into the pockets of shareholders everywhere on earthexcept, of course, for the Amazon.