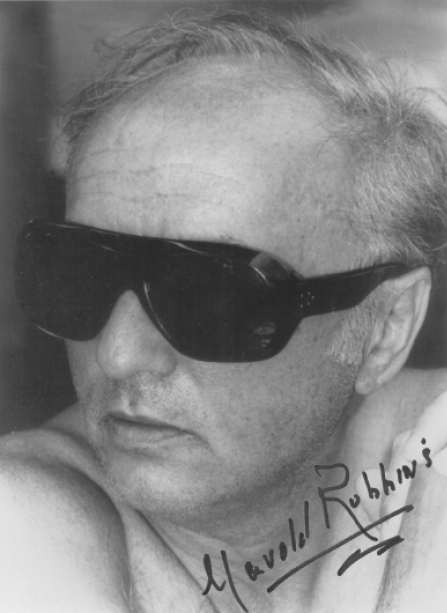

THE ADVENTURERS

THE MOST MAGNIFICENT,

MOST SEDUCTIVE NOVEL

FROM AMERICAS MASTER STORYTELLER

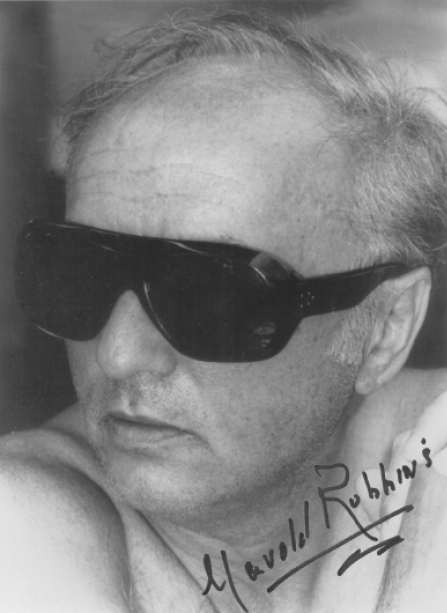

HAROLD ROBBINS

HAROLD ROBBINS IS A MASTER!

--Playboy

ROBBINS BOOKS ARE PACKED

WITH ACTION, SUSTAINED BY A STRONG

NARRATIVE DRIVE AND ARE

GIVEN VITALITY BY HIS

OWN COLORFUL LIFE.

--The Wall Street Journal

HAROLD ROBBINS

IS ONE OF THE

WORLDS FIVE BESTSELLING AUTHORS...

EACH WEEK, AN ESTIMATED

280,000 PEOPLE... PURCHASE A

HAROLD ROBBINS BOOK.

--Saturday Review

ROBBINS GRABS THE READER

AND DOESNT LET GO...

--Publishers Weekly

The Adventurers

by

HAROLD

ROBBINS

AuthorHouse, Inc.

Books by Harold Robbins

The Adventurers

Descent from Xanadu

The Dream Merchants

Dreams Die First

Goodbye, Janette

The Inheritors

The Lonely Lady

Memories of Another Day

Never Love a Stranger

The Pirate

Spellbinder

Where Love Has Gone

AuthorHouse

1663 Liberty Drive

Bloomington, IN 47403

www.authorhouse.com

Phone: 1-800-839-8640

Copyright 2010 Jann Robbins.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval

system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying,

recording, or otherwise, without the written prior permission of the author.

First published by AuthorHouse 6/25/2010

isbn: 978-1-4520-4567-2 (sc)

isbn: 978-1-4520-4568-9 (dj)

isbn: 978-1-4520-4569-6 (e)

Printed in the United States of America.

Bloomington, Indiana

The womb shall forget him;

the worm shall feed sweetly on him;

he shall be no more remembered.

JOB XXIV:20

CONTENTS

VIOLENCE

and

POWER

POWER

and

MONEY

MONEY

and

MARRIAGE

MARRIAGE

and

FASHION

FASHION

and

POLITICS

POLITICS

and

VIOLENCE

It was ten years after the violence in which he died. And his time on this earth was over. The lease he held on this last tiny cubicle of refuge had expired. Now the process would be completed. He would return to the ashes and the dust of the earth from which he had come.

The tropical sun threw waves of white-hot humidity against the black-painted crosses on the white clay cemetery walls as the American journalist got out of his taxi at the rusted iron gates. He gave the driver a five-peso note and turned away before the driver had time to say, Gracias.

The little flower stalls were already busy. Black-clad women were buying small bunches of flowers, their heavy dark veils seeming to shield them from the heat and the world from their grief. The beggars were also there, the little children with their large dark eyes set in hollow black circles, their bellies swollen with hunger. As he passed they held out their grubby little hands for the coins he negligently dropped into them.

Once through the gate there was silence. It was as if some master switch had turned off the world outside. There was a uniformed man sitting in an open booth. He went over to him.

Xenos, por favor ?

He thought there was a faint expression of surprise on the mans face as he answered, Calle seis, apartamiento veinte.

The American journalist turned away smiling. Even in death they clung to the routines of living. The paths were called streets and the buildings within whose walls they rested were apartments. Then he wondered about the surprise on the mans face.

He had been in the lobby of the new hotel, leafing through the local newspapers as he always did whenever he came into a new town, when he found the notice he had been searching for. It was a tiny four lines buried amidst the back pages, almost lost in the welter of other large notices.

He was walking down a path of elaborate private mausoleums. Idly he observed the names. Ramirez. Santos. Oberon. Lopez. He sensed the chill coming from the white marble despite the heat of the sun. He felt the perspiration damp and cool on his collar.

Now the path had widened. On his left were open fields. There were small graves in them. Small, untended, forgotten. These were the graves of the poor. Thrown into the earth in flimsy wooden caskets, left to disintegrate into nature without care or memory. To his right were the apartados . The tenements of the dead.

They were big buildings with red and gray Spanish tiled roofs, twenty feet high, forty feet wide, eighty feet long, of white cement blocks, three by three, and cheating a little on each side so that more tenants could occupy the walls they filled. Each three-foot square bore the name of its tenant, a small cross above the name etched into the cement and the date of death below.

He looked up at the first building. There was a small metal plate attached to the overhanging sheaf. CALLE 3, APARTAMIENTO 1. He had a long way to walk. The heat began to pour into him. He loosened his collar and quickened his pace. It was almost the time and he didnt want to be late.

At first he thought he had come to the wrong place. There was no one there. Not even the workmen. He checked the metal plate on the building, then the time on his wristwatch. They were both correct. He opened the newspaper to see if he had mistaken the date but that was right too. Then he let out a soft sigh of relief and lit a cigarette. This was Latin America. Time wasnt as exact here as it was at home.

He began to walk slowly around the building, reading the names on the squares. At last he found what he was looking for. Hidden in a shaded corner under the overhang on the southwest corner of the building. An instinct made him throw down his cigarette and remove his hat. He stared up at the inscription.

He heard a creaking wagon on the cobblestones behind him. He turned toward the sound. It was an open wagon drawn by a tired burro, its ears flat against its head in protest at being forced to labor in the heat. The wagon was driven by a laborer in faded khaki work clothes. Next to him on the seat was a man dressed in a black suit, black hat, and a starched white collar already yellow from the sweat and dust of the day. Beside the wagon walked another laborer, a pickax over his shoulder.

The wagon creaked to a stop and the black-clad man clambered down from his seat. He took out a sheet of white paper from his inside coat pocket, glanced at it, then began to peer along the walls at the nameplates. It wasnt until he came to a stop before him that the journalist realized that they had come to open the vault.

The man gestured and the laborer with the pickax came over and stared up at the cubicle. He muttered something in soft Spanish under his breath and the other laborer wearily climbed down from the wagon, pulling behind him a small ladder made of pieces of wood nailed together. He placed it against the wall and climbed up. He peered closely at the cement-block vault.

Dax, he said, his voice unnaturally harsh in the muted cemetery.

The director nodded. Dax, he repeated in a satisfied voice.

The laborer with the pickax nodded also. There was a sound of pleasure in his voice. Dax. He spat into the dust at his feet.

The laborer on the ladder held out his hand. El pico.

The other laborer handed the small pickax up to him. With a tight expert blow the man on the ladder sent the pickax smashing into the dead center of the concrete block. It splintered in radiating lines tearing through the chiseled lettering in all directions just as the sun crossed the corner of the overhang. The laborer cursed at the sudden sun and pulled his hat down over his eyes. He slammed the pickax into the cement again. This time the stone broke through and pieces came flying down, rattling against the cobblestones.

Next page