Table of Contents

For Stephanie & Roxanne With Love

AUTHOR S NOTE

Trial lawyers will tell you that the least reliable witnesses are eyewitnesses. I had difficulty grasping this idea until I saw Akira Kurosawas film Rashomon, which succeeded in persuading me of the evanescent nature of Truth.

Truthlike Beautyappears to lie in the eye of the beholder.

In writing this book, I have primarily used my memory, with some ancillary research to remind me of certain events and dates, but what follows must surely be taken as an eyewitness account.

In the interest of treading that fine line between tact and truth, some names have been changed.

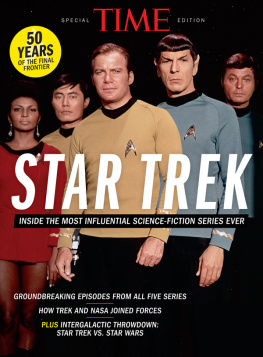

So here goes my memoir. As the title suggests, it is about my experiences in Hollywood, making and trying to make movies, with a special emphasis on my encounters with the phenomenon known as Star Trek. Over the years, Ive been asked a lot of questions about the Star Trek movies with which I was involved. Sometimes I feel like those guys in noir movies being grilled under the glaring light of a lone gooseneck lamp, while interlocutors hover in the shadows: All right, lets go over it again... But Ive told youIve told you a thousand times, told you everything I know! I wail. I told you on the DVD! I told you on the Special Edition! Ive told you on Blu-ray! Tell us again, they insist. The temptation at such times is to embroider, for my sake if not for theirs. To vary the facts as I recall them, throw them a bone, start imagining things instead of remembering them. I will try my best to resist such temptations here.

But this book isnt just about Star Trek. Ive taught classes in screenwriting and Ive found myself reflecting on the unique perspective my background afforded me as a stranger in a strange land and the adventures Ive had trying to make the movies I wanted to watch. When I started out heading for California to make movies, what I was doing was considered unusual. At best. There werent film courses being offered in high schools back then and only a few were starting to be available in universities. Nowadays my children study Italian neorealism and American film noir; when I was sixteen, I played hooky watching the stuff on Broadway and 88th Street or caught it on late-night television.

Everybody got their popcorn?

PART 1

PRE TREK

PROLOGUE

A FUNERAL

It was December of 1982 and Verna Fields was dead. The woman known as Mother Cutter, editor of Jaws, had died, aged sixty-four, of cancer and a memorial service was being held at the Alfred Hitchcock Theater at Universal Studios. I had known Verna socially and like many other young directors, I had benefitted from her counsel, support, and advice. She would take me to lunch and afterward treat me to an expensive cigar from the humidor of a nearby tobacconist. Verna, I would protest, how are you paying for this? Shed grin merrily behind large glasses. Im wooing you, baby, Im wooing you. She was a brilliant editor so of course after Jaws theyd made her an executive and stuck her behind a desk, which you might say was like promoting Captain James T. Kirk to Admiral. What a waste.

Anyway, there we all were, crammed into the intimate Hitchcock Theater, listening to Ned Tanen, head of Universal and a devoted friend of Vernas, deliver the eulogy. Tanen, who had a mercurial temperament and was as prickly as the cacti that he loved to grow, opined that Verna Fields had been the only decent human being in this dirty, rotten stinking townor words to that effect. The thing about funerals, I find as a rule, is that you dont listen to such speeches critically. People say some outlandish or exaggerated things, carried along in the currents of emotion and the moment, so I dont suppose I blinked at Neds impassioned words. I just sat there and felt sad thoughts.

It was only later, standing alone outside the theater, surrounded by people chatting together in little knots while waiting to leave for cold cuts at Vernas house, that I became aware of someone else speaking. If this were a film and we were mixing this scene, the voice that impinged on my idling consciousness would be dialed up slowly and would go something like this:

... biggest crock of shit I ever heard in my lifemind you: I take a backseat to no man where my affection for Verna Fields is concerned but I dont think I would have lasted thirty years in this business if I hadnt found it to be populated by some of the kindest, most loyal, generous, talented, and loving people I could ever hope to meet in this or any other lifetime.

It was as if someone had thrown cold water on my face. The speaker, when I turned to look, was Walter Mirisch, a producer whose list of great movies is probably as long as George W. Bushs war crimes.

Yes, I thought, decisively. This is true. I hadnt been in the business anything like thirty yearsit was more like tenbut since my arrival in Los Angeles, a stranger in a very strange land, I had met with as much kindness, generosity, and support as I had found anywhere else. Maybe more. Me and Blanche DuBois.

EARLY DAYS

And in those ten years I had certainly needed (and continue to need) all the help I could get. One group I came to envy as I got to know them were children of those already in the business. Not that all of them were happy or even prospered, but like medieval stonemasons or shipwrights, they seemed to be part of a familial continuity that I didnt possess. There was Steven-Charles Jaffe, for instance, who with his father, Herb, produced the first film I wrote and directed, Time After Time. I envied father and son their professional bond. Herb told me, I am a lucky man; I get to see my son every day. I had no such family anchor in Los Angeles. For years I was always conscious of being on my own in California, the boy who had run away to join the circus that was movies. Nobody from the world in which I grew up was in show business. The children of my parents friends followed their footsteps and became doctors or lawyers or went into business (whatever that was); I was the only one I knew who wanted to go to Hollywood and make movies. I must have set the fashion, for later everyone did. I dont think movies at that time were even regarded as a profession. The famous stars and directors hadnt studied to become filmmakers; they had sort of fallen into it. Second unit directors had begun as cowboys. Some were in fact Indians.

In the years to come I would meet and become friends with many people in the business whose fathers or mothers had been in it before them. This conferred a kind of tradition on the whole enterprise, or at least to my way of thinking a legitimacy that I sorely lacked and missed. My own family never quite understood what it was that I was doing or attempting to do, even though it was tacitly acknowledged that I wasnt fit for much else. My father always was an astute and subtle critic of anything I wrote, a wonderful editor, but there his involvement ceased. In the years that followed, no matter how successful I became, or even how proud they were of my success, my parents never made it their business to master the nomenclature or glossary of terms that would have enabled them to better understand what I had to tell them about my life.

Mom, Im in preproduction.

Uh huh. Whats that?