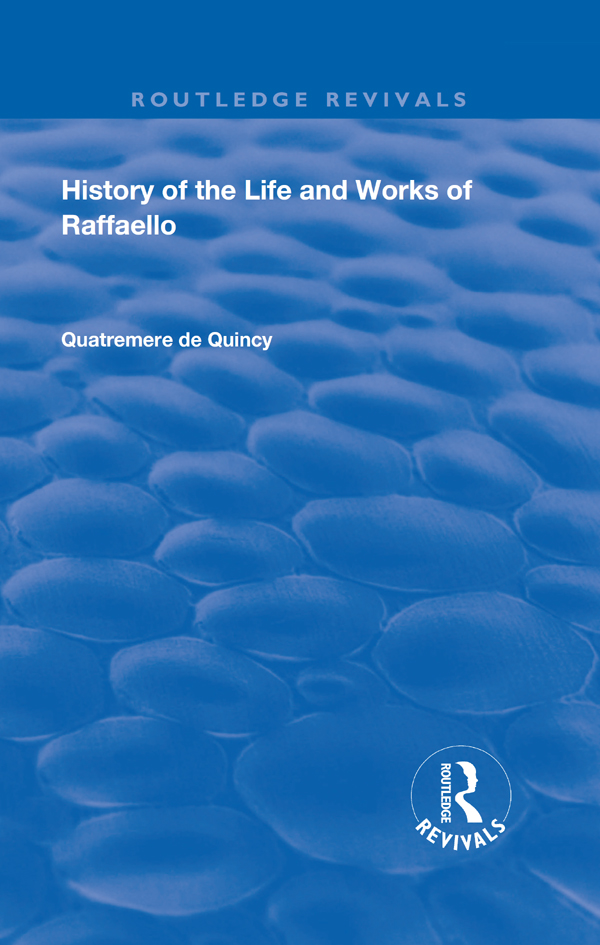

HISTORY

OF THE

LIFE AND WORKS OF RAFFAELLO.

_______________

I T was the small town of Urbino, in the Papal States, which, on the 28th March, 1483, gave birth to Raffaello Sanzio. The patronymic was originally De Santi, or Sancti, but custom had italianized it into Sanzio.

The family was of ancient date at Urbino, where it had maintained itself with honour in a moderate condition of fortune. It had a genealogy set forth in Latin on a scroll of paper, that Antonio de Santi, son of Giulio, the head of the family, held in his hand, in a portrait of him formerly in the possession of cardinal Giovanni Francesco Albani, who became pope under the name of Clement XI.

Upon the house where he was born there is an inscription, to mark with honourable distinction the place of his birth; it terminates with these lines:

Ludit it in humanis divina sapientia rebus

Et spe in parvis claudere magna solet.

The genealogy runs thus:Giulio de Sancti, cousin to Tiberio Bacco, a Roman citizen of great eloquence, was the first of the family De Sancti, still honourably known at Urbino, who assumed this cognomen. From him descended Antonio de Sancti, who is painted here. He gave birth to Giovanni Giacopo, a learned canon; to Giovan-Battista, a brave officer of infantry ; to Galeazzo, a noted painter; to Sebastiano, and to a daughter. Galeazzo begot Giulio, a celebrated painter, and compiler of this genealogy; Antonio and Vincenzo, both painters, and other sons and daughters. Of Sebastian were born Girolamo and Giovan-Battista. Of Giulio, Galeazzo, Curzio, Annibale, and other sons and daughters. Of Antonio, Claudio, and several daughters. Of Giovan-Battista, son of Sebastian, Giovanni, father of Raffaello. Bellori adds:Antonio is painted in a half-length, wearing a dark habit of antique fashion, lined with fur, and with a cap on his head. On the table near him is a book, inscribed Appiano Alessandrino, indicating his profession of historian and man of letters.

This genealogy, for a copy of which we are indebted to Bellori, contains the names of a succession of Urbinese citizens, well known in their native town, where they had exercised various professions, and had served the state in various employments. Among them we remark several painters, Eaffaello being the fifth of the family who practised the art. The profession, however, was all he inherited from them; for none had his genius or his reputation.

Not that Giovanni Sanzio, his father, was destitute of ability. More than one production of his pencil demands from the impartial critic the acknowledgment that, notwithstanding a feebleness of colouring, and a timidity of style inseparable from that early stage of the revival of art, they manifest unequivocal indications of a progress full of promise for the future. The researches which have been made in Italy for worthy productions of art, anterior to Raffaello, have placed several works by his father in an honourable position on the interesting list. One rare merit he possessedthat of not imagining himself greater than he really was, and of comprehending that his own talent would be wholly surpassed by his sons. It is to this noble modesty, perhaps, that we, in a great measure, owe Raffaello.

Among them we have noticed a St. Elizabeth with the Virgin on a throne; a Visitation of St. Elizabeth, in the church of the Minori Osservanti; the Virgin on a throne, with Infant Jesus and Infant St. John, at Berlin, &c. Baldinucci names five historical works of Giovanni Sanzio as still remaining in Urbino.

While yet an infant, Giovanni Sanzio bestowed upon him all the earnest attention which an only and long-desired son can receive from a tender father. He knew that if the habits of men take their origin from the earliest moments of their existence, the education which is to guide them should also commence with their infancy; that it is in infancy they should hear from their mother those first lessons which derive their virtue from the domestic affections. With the maternal milk Raffaello seems to have imbibed the taste for painting. His first playthings were the implements of his fathers art; and the latter delighted on all occasions to encourage tendencies which seemed the presage of an extraordinary vocation to the noble art he himself so loved.