TRANSLATORS INTRODUCTION

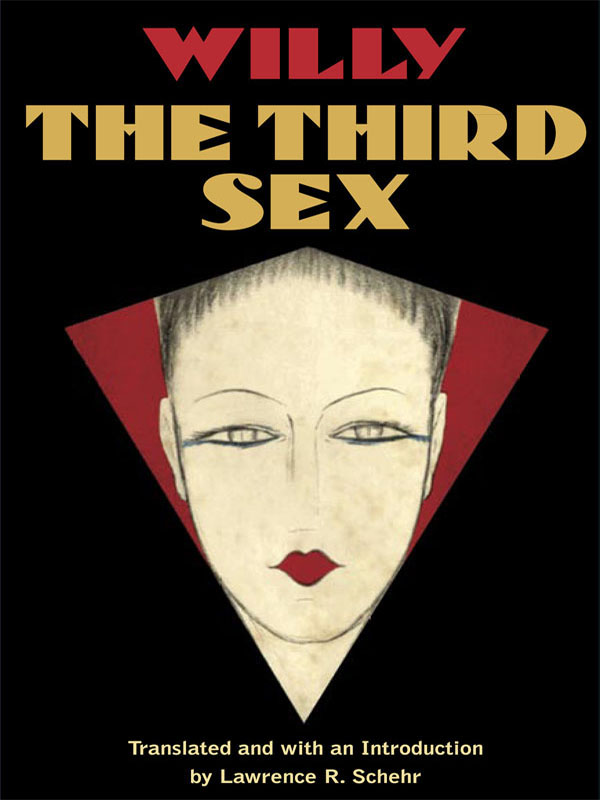

Toward the end of a long life on the Parisian literary scene, Willy turned his sights to a topic that was new to him, a seeming radical departure from his usual interests in the demimonde, in Montmartre, in potboilers about women with modern morals, and in tales about the Parisian stage and Parisian nightlife: he turned to male homosexuality. Though an unapologetic, rather sexist heterosexual who had occasionally engaged lesbianism as a titillating figure in the male heterosexual imaginary, Willy seemed at this point to be looking at a subject that was foreign to him in more ways than one. Yet as always, Willys instincts were on target: male homosexuality was in the air; in many ways it was the subject of the twenties. If womens liberation and modernization were ultimately more important in the great scheme of things, they were normal, even as they challenged long-held ideological beliefs, the patriarchal state, and the models of bourgeois family life. But homosexuality was unexpected in so many ways, yet it was making a splash on the Parisian scene, in the work of Marcel Proust and Andr Gide, and, across the borders, in the gay liberation movement in Weimar Germany. But before that, who was Willy?

Born Henri (or Henry) Gauthier-Villars in 1859, the author, drama critic, and music critic known as Willy or Monsieur Willy rose to prominence in the 1880s and was an important figure on the Paris art and cultural scene by the end of that decade. He is most remembered today as the first husband of Colette, whom he married in 1893; her first novelsparts of the Claudine serieswere written by her and published under his name. The anecdotes about those works are legion: Willy would lock her in her room for several hours a day until she wrote the requisite number of pages, and he insisted on the more scabrous episodes being included in Claudine lcole [Claudine in School] and Claudine en mnage [Claudine at Home]. Finally tired of the abuse, Colette broke free of Willys yoke and went on to have the career with which all readers of twentieth-century literature are now familiar.

Some of these writers had distinct careers, such as Curnonsky, who with another collaborator, Marcel Rouff (himself the author of La Vie et passion de Dodin-Bouffant), was the coauthor of regional guides to restaurants in France in the 1920s. Some had more modest careers, like Suzanne de Callias, who wrote for Willy under the pen name Menalkas (in a not-so-subtle reference to Gides LImmoraliste [The Immoralist]), known at the time for writing novels about modern women. But by and large, these authors produced potboilers for Willy, which at times he peppered with his own wit, and at other times he just let them go as they were. And in some casesand this is indeed the case for Le Troisime Sexeone is safe to assume that Willy did not write the book, but the real author remains unknown to this day.

The 1920s were a time, in France and elsewhere, of rapidly changing mores. As Paris had become the capital of the nineteenth century, to use Walter Benjamins well-known expression, city life in Paris, London, Berlin, New York, and elsewhere took on an ever increasing complexity. By the turn of the century, these cities and others were destinations for many people from the countryside who, for one reason or another, sought a new life in the relative anonymity that was possible in the city. In the aftermath of the First World War, city life burgeoned. Men and women had been uprooted by the war; they flocked in record numbers to these cities that were rapidly turning into the sites of cosmopolitanism. No longer just the symbolic or political capitals of nineteenth-century nation-states, these cities were international cities, homes to colonial power, be it real or economic, and sites for immigration both within the country and from the outside.

These cities were patchworks, homes to a variety of subcultures that coexisted rather peacefully alongside one another. Paris, for example, was the home to American expatriates, both black and white, people from the country, people from the colonies, an artistic and cultural community that included, at various times, Pablo Picasso, Gertrude Stein, Josephine Baker, the surrealists, Maurice Chevalier, and others too numerous to mention. Film and radio were making forays into decentered, impersonal representation of knowledge and image outside of family, school, and church. Public transportation such as the Paris metro, the London Underground, and the New York subways and complex bus systems made movement easier within the cities. Geography was no longer an issue as the local expanded.

And, as one might easily imagine, each of those cities, along with many others, had a thriving gay subculture, with venues often localized in one part of town. This was not the first moment in recent memory in which there were obvious gay subcultures. One need think only of George Chaunceys excellent volume on the gay community in New York in the nineteenth century or even the scandals of the time, be it the Oscar Wilde trial or the Eulenburg affair, to recognize that these communities had existed for quite a while. What changed after the war were both the visibility and the complexity of these communities. With an influx of new populations, with a relatively progressive laissez-faire attitude reigning in many places after the war, and with a new mobility within the cityscape, these communities developed, with various venuesbars, theaters, meeting places, cruising spotsbecoming regularized, patronized by groups of local gay men, and often visited by tourists: sex tourists looking for adventures or just curious onlookers seeking out how these curious, queer folks lived their lives.

And it should be noted that whereas in Paris, at least, consensual gay sex in private between adults was not illegal, it remained illegal, in one form or another, in the three other cities mentioned. Oscar Wilde had been condemned under the United Kingdoms sodomy laws that would not be abrogated until 1967, ten years after the Wolfenden Report recommended decriminalization. In New York and many other states, sodomy laws would remain on the books for years to come: Illinois was the first state to strike down its sodomy laws, in 1962, but the final ones lingered until the Supreme Court decision Lawrence v. Texas in 2003. In Germany, the infamous Article 175 of the German penal code that criminalized homosexuality was a cause clbre, and it was the rallying point for what was arguably the first gay rights movement, centered on the figure of Magnus Hirschfeld.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.