WILL BUCKINGHAM is a writer of fiction and non-fiction for adults and children. He has worked at universities in the UK, China and Myanmar, most recently as visiting professor of Humanities at the Parami Institute, Yangon. He is the author of Sixty-Four Chance Pieces and Lucy and the Rocket Dog .

AN EXORCISM OF SORTS

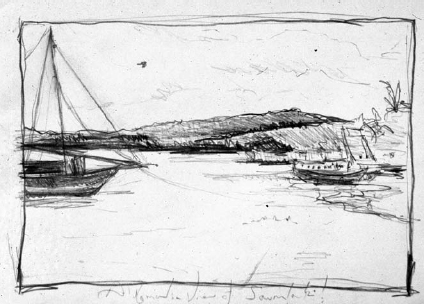

I still dream of Tanimbar. I dream of scattered islands and atolls, of rocky bluffs and of cliffs that plunge down into the blue-green water. I dream of fleets of outrigger canoes putting out to sea for sea cucumber. I dream of journeys on foot up the coast roads at night, the stench of forest buffalo hanging in the air. I dream of frigate birds that wheel and circle over my head. I dream of heirloom gold that flashes in the sunlight like the plumage of fighting cocks. And I dream of the sun, shattered into a million parts. These dreams do not come frequently, but when they do I wake with a nagging sense of unease, a mixture of nostalgia and gratitude and regret.

The last time I dreamed of Tanimbar was some months ago. The dream was so vivid that when I woke in the pale light of an English spring morning, my heart beating fast, it took me a few moments to realise where I was. Beached upon the sheets in the morning light, feeling the tides of the dream pull back, I realised that it was twenty years since I had touched down in Saumlaki.

Later that morning, I took down the old cardboard box that sat on top of my bookshelves and opened it up. Inside were sheaves of letters, tattered photocopies, plastic boxes of photographic transparencies. I held up the slides against the light, one by one. The transparencies were turning green with age. Each slide was like a tiny illuminated flash of memory. As I looked through the slides, names and half-remembered Indonesian phrases returned to me. I had a strange sense that I had unfinished business with Tanimbar, or that Tanimbar had unfinished business with me. I had debts to discharge, obligations to meet, even if I was not sure what these debts and obligations were.

I packed the slides away. It was then I realised that after two decades I wanted to write about Tanimbar. I wanted to pass on the stories I had been told, to trade in things half remembered and half forgotten. It would be an exorcism of sorts. It would be what in Tanimbar they call or they once called a mandi adat , a ritual-law bathing that squares all accounts with the past.

I packed the slides and the photocopies and the letters away. Then I went out into the spring morning to clear my head.

I flew to Tanimbar at the age of twenty-three, a fledgling anthropologist. A few years before, whilst enrolled at university as a somewhat lacklustre student of fine arts, I had stumbled across the anthropology section in the library and I was immediately enchanted. From the very start, what anthropology taught me was that the possibilities for human life were many. Anthropology sang praises to the malleability of human existence. The more I read, the more I came to see that the things I took to be common sense, the things that I believed were simply the way things were , were nothing of the sort. Kinship, marriage, ethics, law, religion, life, death, politics everything that mattered seemed up for grabs. Anthropology was an escape route, a back door by means of which I could slip the net of my own assumptions and beliefs.

So, instead of spending my days in the art studio trying to wrestle with the intractability of paint and canvas, I took to hunting and gathering in the library amongst the anthropology stacks. I read about the Nuer, the Mbuti, the Azande, the Trobrianders, the Ik and the Toraja. And sometime midway through my art degree I decided that, like thousands of anthropologists before me, I too would go out into the field and engage in some ethnography that curious brand of high-minded intrusiveness amongst peoples too polite, or too powerless, to tell you to go fuck yourself.

I started to make plans. And I came, by degrees, to settle on the Tanimbar Islands, a small archipelago set at the end of the long arm of volcanic islands that stretches from Sumatra to Java to Bali and Lombok to Nusa Tenggara and Timor. There were tantalising suggestions that Tanimbar had strong traditions of carving in wood and stone. I decided I would go to Tanimbar to find out more about these traditions, and to meet the artists who still worked there.

Undaunted by the fact that I had no qualifications in anthropology whatsoever, I wrote a research proposal for the Indonesian Institute of Sciences, and contacted universities in Indonesia to ask if they would work with me. I visited museums in London and in the Netherlands. In dusty storerooms I gazed at beautifully carved house-altars, or tavu , adorned with swirling wave patterns; at squatting ancestor figures, or walut ; and at kora ulu prow boards from war canoes, decorated with fighting cocks. Meanwhile, I opened a bank account and started to apply for grants to fund my trip. The money began to trickle in.

Somehow, by the time I graduated from my degree, I found myself with a bundle of permission letters, the backing of the University of Pattimura in Ambon, a permission letter from Lembaga Ilmu Pengetahuan Indonesia the Indonesian Institute of Sciences and a small research budget to pay for the trip. All this is how, towards the end of the summer of 1994, I came to catch a flight to Indonesia.

At the heart of the story that follows are my encounters with three remarkable sculptors Matias Fatruan, Abraham Amelwatin and Damianus Masele. My instructors, guides and accusers, these three men taught me lessons that I am still struggling to fully master. I am indebted to them. But this book is about other things besides. It is about possession and exorcism, sickness and healing, time and history, uncertainty and change. And it is about how I eventually took fright at the prospect of becoming an anthropologist, and how I came to leave behind anthropology the art, as Matias Fatruan put it, of stealing with the eyes for good.