I.

An English gentleman, Mr. John Lambert, who visited New York in 1807, when the entire city lay below Canal Street, was severely critical in regard to the churchyards on Broadway. In his diary, after speaking of Trinity Church and St. Paul's as " both handsome structures," he added: "The adjoining churchyards, which occupy a large space of ground railed in from the street and crowded with tombstones, are far from being agreeable spectacles in such a populous city." The population of New York in that year, as he gives it, was 83,530, and in our more modern eyes would betoken rather an overgrown village than a metropolis.

In still another part of his journal, Mr. Lambert returns again to the assault on the churchyards, and insists that they are " unsightly exhibitions." " One would think," he says, " there was a scarcity of land in America to see such large pieces of ground in one of the finest streets of New York occupied by the dead. The continual view of such a crowd of white and brown tombstones and monuments as is exhibited in the Broadway must tend very much to depress the spirits." Now, if it is well to see ourselves as others see us, we have here a very plain-spoken opinion about our city graveyards from the pen of a traveled Englishman, who generally spoke in terms of nothing but praise concerning the young metropolis, its inhabitants and their customs. But it is a poor rule that will not work both ways, and the fastidious critic might have found it profitable to carry a mirror in his trunk.

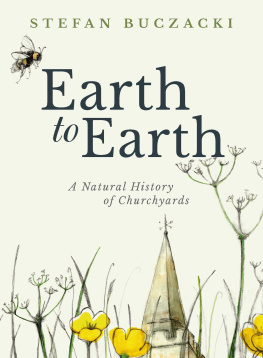

As a citizen, and not a stranger, I find few so attractive spots as these churchyards on Broadway. People write sentimentally about sleeping under the grasses and daisies of the country, and one good Bishop years ago dropped into poetry and requested to be so interred. But it has always struck me that the rural cemetery is intolerably lonesome. Even if the sleepers there do not need the comradeship of the living, it is undeniable that the grass is as green, the sunshine as golden, and the flowers as fragrant in the glebe around St. Paul's and Trinity, as where no piles of brick and mortar have blotted out the fields.

The dead have company here. The feet of the living pass up and down the street hard by, and among these footfalls are those of descendants of the quiet ones of men who admire their record and women who love their memory. They are sleeping, too, in the shadows of the homes in which they lived and were happy. The roar of business is around them as they knew it in life, and once a week comes the quiet of the Sunday they observed. If no longer the waves of the river break against the pebbly beach that at first bounded St. Paul's churchyard, and through the bluff which looked down into the waters of the Hudson back of old Trinity, a street now passes, with two more streets of artificial make beyond, the burial place of the dead is there unchanged.

I have long believed that Trinity Parish has done New York no one greater benefit than in leaving the breathless dead to be companions to the thoughtless living. It is true, O eminent philanthropist, that these acres might have been sold for many pence and the money given to the poor; equally true, Sir Speculator, that the dust of the dead could not have resented being carted away to other dust heaps, but something would have been lost to the living that no power of earth could restore. I never pass these colonies of tombstones without thanking the men who have stood sentinel over them and kept them in place. As they stand in their impressive silence, tall shaft and crumbling slab, they are more eloquent than any sermons, more full of tears and pathos than any print can create, more prompt to teach faith and hope than so many volumes of dogmatic theology. They who sleep beneath are not the dead, but the living. We know about them; have read of their faults and their virtues; have been told how they dared and endured; have looked into their eyes in galleries of old portraits, touched the hem of their garments still cherished by their grandchildren, held in our hands the little battered spoon in which their childish teeth made dents so many years ago. Go to! We are the dreamers and they are the folk of action. You shall be passing any night when the moon is shining on these grasses and look through the iron rails that keep out a disturbing world, and every stone shall cry out to you from its sculpturings and make you long to know the story of the ashes that was once a man or woman of your world, and then you shall turn away and gaze upon the painted names of men that gleam from the walls of buildings across the way and that eagerly announce their business to the world, and you shall feel no such throb of sympathy nor sense of weird comradeship as when your face was set towards the dead. Did I not say that we are the dreamers?

There is no pleasanter spot in New York than the churchyard of old Trinity on a quiet Sunday morning in the Summer. There are flowers and grasses, the shade of graceful elms, fresh air and the twittering of birds even the oriole and the robin still come back there every year in spite of the aggressive sparrow and there is no end of companionship. It is a companionship which I like, because it is open and free. Here every man, woman and child, except the unquiet prowlers above ground, presents to our eyes a card of granite or marble, gravely telling his or her name, age and a few other particulars set forth, more or less elaborately a quaint custom, but not a bad one for the living to adopt, if they would be equally frank about it.

Even in the days when the present church building was new more than forty years ago by the calendar I found no more pleasant place in which to pass a half hour as a boy. It was a more unkempt place then, than now, and bluebirds and thrushes were more frequent visitors. I found an endless pleasure in tracing the inscriptions on the tombstones, and it was not long before I had familiar acquaintances, heroes and heroines, in every corner. Huge was my delight, too, when, with two or three companions, we could escape the eye of old David Lyon, the sexton, and lie down into the crypt beneath the chancel. There we saw yawning mouths of vaults, revealing to our exploring gaze bits of ancient coffins and forgotten mortality, and we poked about these subterranean corridors with dusty jackets and whispered words, finding its atmosphere of mold and mystery a strange delight. For somehow the unknown sleepers, then who seemed to have no means of making themselves known unless it was through the musty tomes of Trinity's burial records took strongest hold upon our sympathies, to say nothing of our curiosity.

Everybody who passes old St. Paul's can read for himself the patriotism of General Montgomery, the civic virtues of Thomas Addis Emmet and the eminence of Dr. McNevin, for monument and shaft tell the story. So all visitors to the churchyard of old Trinity easily learn which are the tombstones of Alexander Hamilton, Captain Lawrence, of the Chesapeake, or William Bradford, the first Colonial printer, and where rest the bones of quiet Robert Fulton, the inventor, or dashing Phil Kearney; but there is no herald of the ordinary dead of those who were simply upright men and good women in their day, and there could be none of the unknown dead who are said to far outnumber the lucky minority, the front doors to whose graves still stand and yet preserve their door plate, though the latch-key is gone.