Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2013 by John Clayton

All rights reserved

Front cover, top: Four men in dude cowboy attire stand in front of a bar in downtown Billings, Montana, in 1939. The disparitiesfrontier outfits in front of a neon sign, and silk cowboy clothing now more ornamental than functionalillustrate the continuing influence of the frontier in twentieth-century Montana history. Library of Congress LC-USF33-003092-M3. Bottom: A view eastward down the Swift Current Valley, a former mining district now mostly reserved in Glacier National Park. Kari Clayton photo.

First published 2013

e-book edition 2013

Manufactured in the United States

ISBN 978.1.62584.094.3

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Clayton, John, 1964-

Stories from Montanas enduring frontier : exploring an untamed legacy / John Clayton

pages cm

Includes index.

print edition ISBN 978-1-62619-016-0

1. Montana--History--20th century--Anecdotes. 2. Frontier and pioneer life--Montana--Anecdotes. 3. Montana--Social life and customs--20th century--Anecdotes. 4. Montana--Biography--Anecdotes. 5. Montana--History, Local--Anecdotes. I. Title. F731.6.C52 2013 978.6--dc23 2013010892

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

AUTHORS NOTE

When it comes to the history of Montana and the American West, I say enough with the Indian fights, vigilantes, and cattle drives. What I find compelling is when places start actually filling up with people, such that those activities necessarily fade. In this phase, like a teenager coming to grips with what kind of person he or she is going to be, the region starts developing a personalityone that shapes its future.

As Montanas frontier faded, Montanans started building communities. Of course, there had always been communities in the vaguer sense of the word: links among groups of Native Americans, trappers, soldiers, prospectors, or far-flung ranchers. But physical communitiestowns and cities each with an economic and social and architectural structurecould arise only when there were enough people to both need and create them. So what did that process look like in Montana? What dreams did the states natural splendor inspire? How often did those dreams succeed, how often were they further elevated into myth, and how often did they collide with hardscrabble reality to hone the character of everyone involved? Thats what Im always writing about.

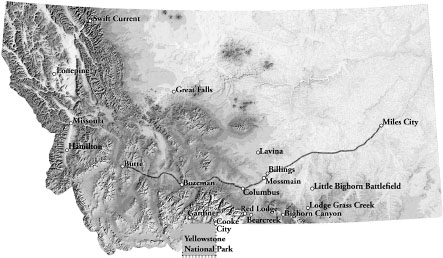

Montana didnt run out of frontier all at once. Along the ButteMiles City railroad corridor (see p. 35), it was vanishing in the 1890s. In the imagined metropolis of Mossmain (see p. 77), the post-frontier age was going to arrive about 1914, but then evaporated. And when I visited a particular spot in the wilderness outside Yellowstone National Park in 2002 (see p. 109), the frontier there seemed to be cantankerously thriving.

Thus, one of the great things about Montana is the way its frontier endured for much of the twentieth century. This untamed legacy created a patchwork, in marked contrast to other places. Consider, for example, Illinois. When sufficient numbers of Illinois homesteads were claimed, forests cut, fields plowed, savages tamed, and fortunes made, the frontier exited Illinois, stage left. In 1840, Illinois was primarily wilderness; by 1860, it was the fourth most-populous state in the Union. And so Illinois advanced. Like teenagers grasping that they will not go into the family business, the burgeoning Illinois communities moved on to more intensive agriculture, processing plants, factories, or whichever other activities best suited their strengths.

In Montana, however, stage left was already taken, and there was no place else for the frontier to go. Sure, there have been claims that the last frontier boldly goes to Alaska, or space, or the Internet. But the traditional view of frontiering (see p. 103) doesnt necessarily follow, instead fading unevenly into Montanas background.

And so, unlike so many other states, as Montana ran out of frontier, Montanans intensified their relationship with it. Indeed, many residents even defined their vacations or communities by it (see p. 131). In part, of course, thats because Euro-American history is so new on this ancient land. It feels more immediate. In part, Montana lacks Illinois moisture-rich soils, navigable waters, and central location. Like a teenager entering the job market during a recession, Montana lacked options to move on to. And in part, the word frontier has come to take on a variety of pleasant meanings: triumphant rural simplicity, a hardship-bred physical and spiritual strength, peaceful naturalism, social naivet, the chance to make a lot of money. Focusing on a disappearing frontier allows Montanans to do more than pursue dreamsit allows us to simultaneously pursue apparently contradictory dreams, and do so while seeing ourselves largely in harmony with our neighbors. Although some observers might call that refusing to grow up, I think its a pretty neat way to live a life.

THIS BOOK EXPLORES what happened when Montana ran out of frontier. And rather than a plodding who-when-where of development, it investigates the question through a variety of narratives, portraits, and perspectives. Although it is, for me, the culmination of twenty-plus years of writing about Montana history, I was not really aware of being on a journey. So to the extent this book serves as a journey for you, I hope you can dawdle, pause, doubt, double back, and otherwise stimulate, question, and enhance your own view of Montana and its history.

Some of the locations of the stories contained in this book. Map by Kari Clayton.

A few structural notes: Ive chosen to organize the book by grouping together similar impulses or developments or types of characters. Because these essays were written over a long period, I have simply indicated the date (and, where relevant, the original publication) at the end of each. Although a woman named Caroline Lockhart makes occasional appearances here (because no compilation of my research and writing could avoid such a fascinating character), there is no overlap between this book and my full-length treatment of her life and times in The Cowboy Girl. Finally, although I have dropped all footnotes from this book, for readability, I would be happy to share sources with scholars (contact me through www.johnclaytonbooks.com).

At times, compiling these essays has made me feel strange and vulnerable. Am I really publishing a sort of Greatest Hits collection? Did I really poke into so many corners and issue so many opinions? Seeing them all collected may imply an author more self-assured, ambitious, and even dogmatic than the way I like to think of myself. Yet at the same time these are storiesabout wonderful characters, such as John Liver-Eating Johnston (see p. 145), or quirky programs, such as The Montana Study (see p. 84)that I have particularly enjoyed writing and sharing with people. Im pleased to have a chance to make these stories available in this format, and I hope you too may find some favorites in here.