Published by the Wisconsin Historical Society Press

Publishers since 1855

2010 by the State Historical Society of Wisconsin

E-book edition 2014

For permission to reuse material from Badger Boneyards: The Eternal Rest of the Story, (ISBN 978-0-87020-451-7; e-book ISBN 978-0-87020-485-2), please access www.copyright.com or contact the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. (CCC), 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400. CCC is a not-for-profit organization that provides licenses and registration for a variety of users.

wisconsin history. org

Photographs identified with WHi or WHS are from the Societyscollections; address requests to reproduce these photos to the VisualMaterials Archivist at the Wisconsin Historical Society, 816 StateStreet, Madison, WI 53706.

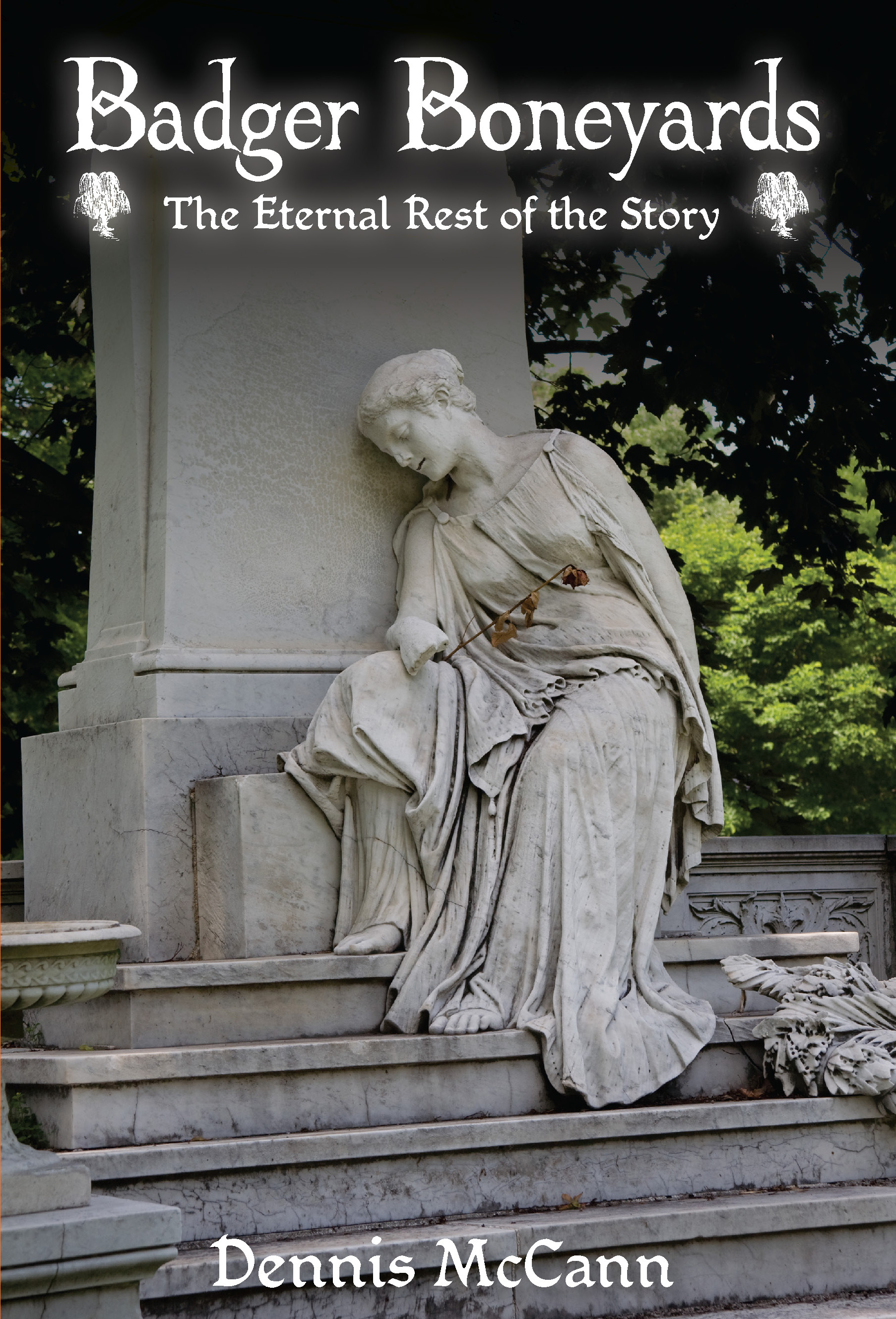

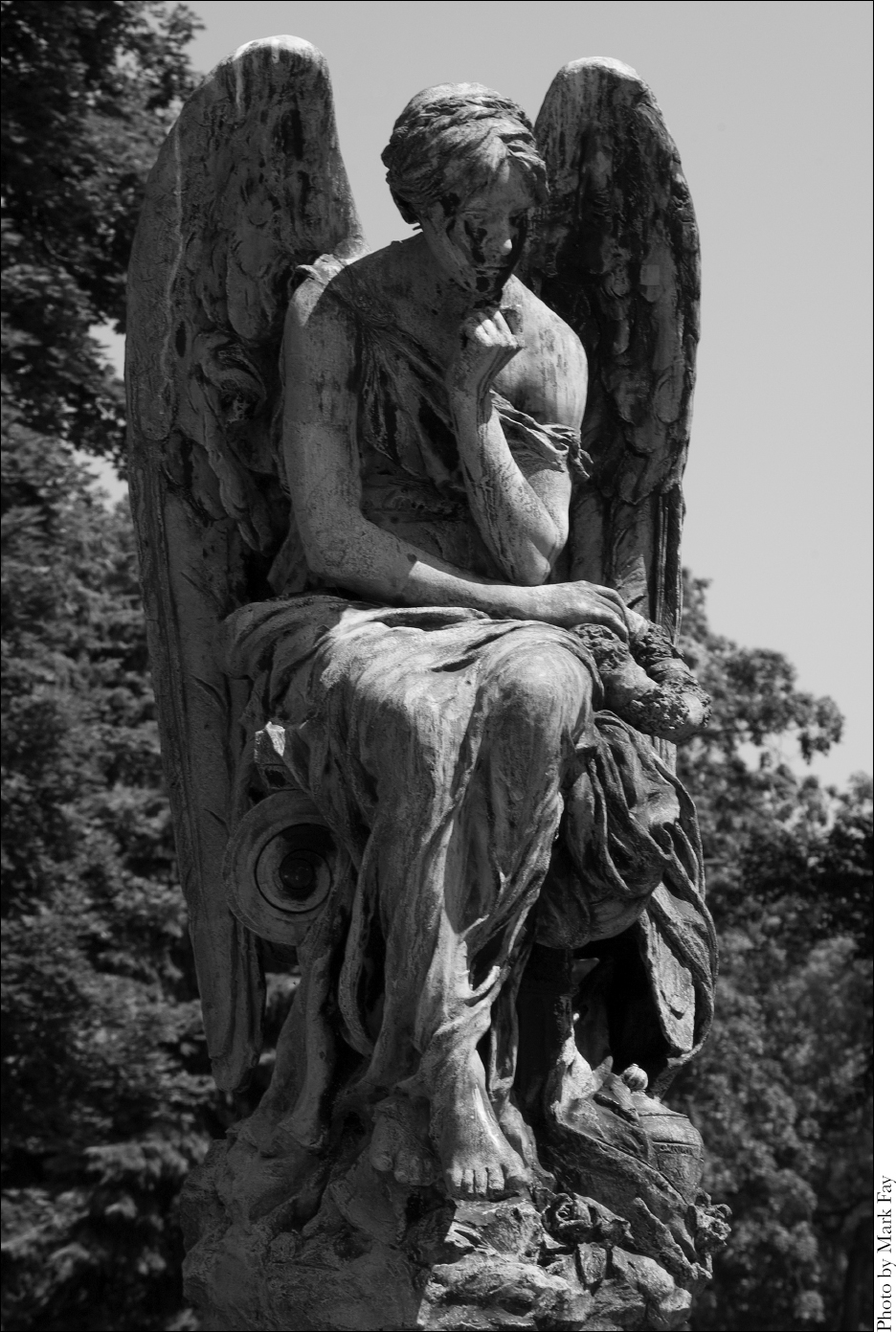

Photographs by Barbara McCann, Dennis McCann, and Mark Fay

Designed by Will Capellaro

14 13 12 11 10 1 2 3 4 5

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

McCann, Dennis, 1950

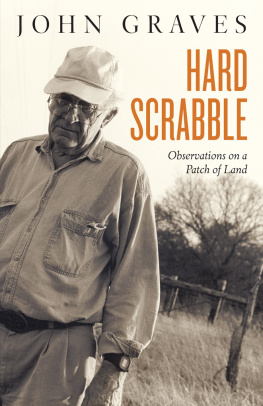

Badger boneyards : the eternal rest of the story / Dennis McCann.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-87020-451-7 (paper : alk. paper) 1. CemeteriesWisconsin. 2. Sepulchral monumentsWisconsin. 3. WisconsinHistory, Local. 4. WisconsinHistoryAnecdotes. 5. WisconsinBiographyAnecdotes. I. Title.

F582.M395 2010

929.5dc22

2009047246

For all of the dead

who give these stories life

Contents

Preface

S ome years ago while in Atlanta on important newspaper businessyes, there is still such a thingI noticed in a visitor guide that the greatest amateur golfer ever, one Robert Tyre Jones, or Bobby to his friends, was buried in historic Oakland Cemetery.

This interested me for two reasons. One, I play golf. Jones, in addition to his spectacular playing career, founded the Masters Tournament, which is played each year at Augusta National Golf Club in Georgia. He was an iconic figure in the game. Two, on another occasion some friends and I had once spent an afternoon trying, quite unsuccessfully, to find the Atlanta house where Jones had lived.

I told Dale, the photographer I was with at the time, that we had to add Oakland Cemetery to our itinerary. Dale was not a golfer. He looked at me as if the fever had claimed my mind. It took two days to persuade him I was serious, but on our last day he agreed we could swing through the cemetery on our way to the airport. When we did, we found Joness grave, mowed short and tight as a putting green and graced with eighteen specimens of plants, one for each hole at Augusta National Golf Course.

While Dale was less than reverent (Instead of a hole in one, he said, hes the one in a hole.), I briefly paid respects.

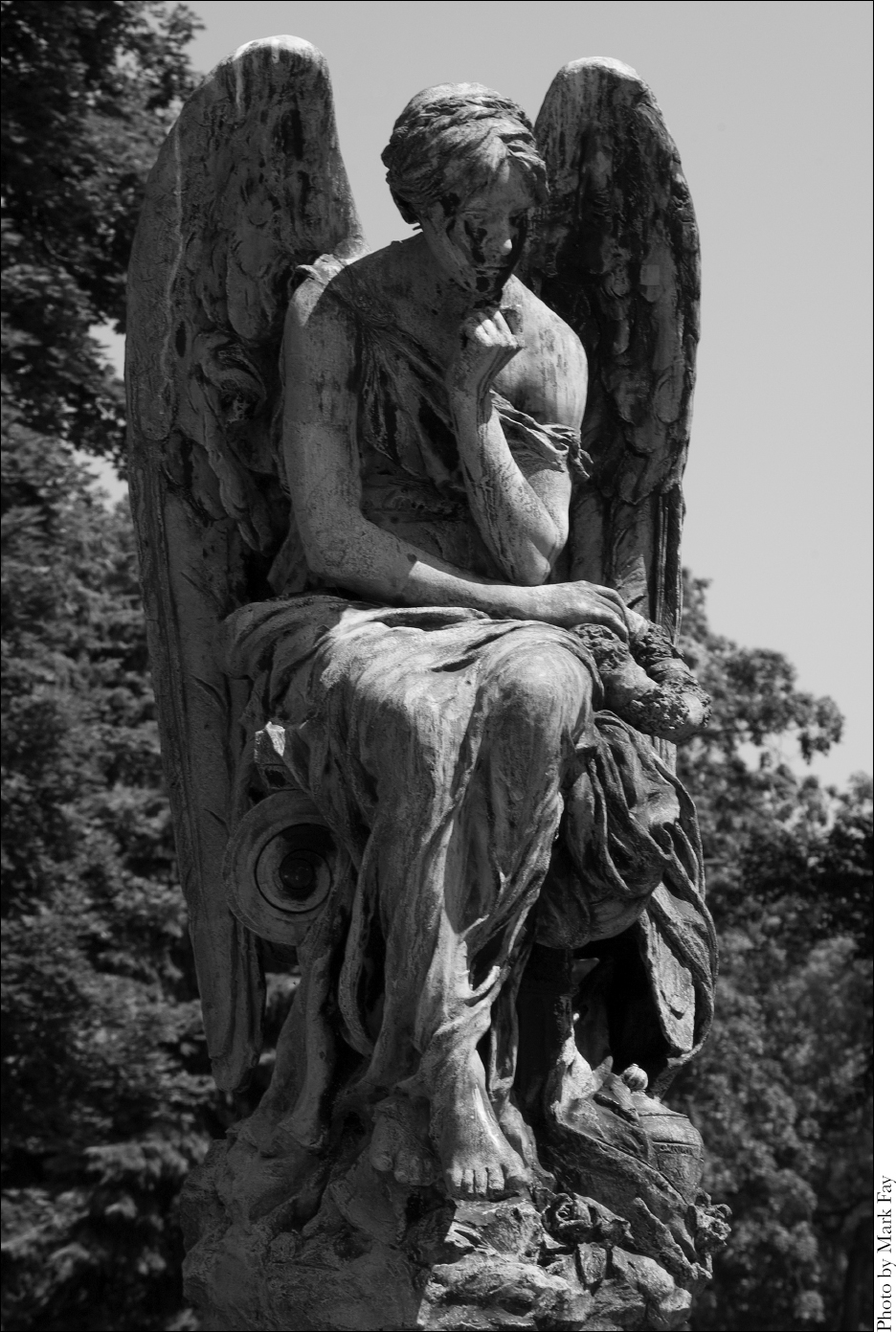

On top of housing the grave of Robert Jones, Oakland was a spectacular cemetery, a quiet city of some seventy thousand residents, with sections for Union soldiers and Confederate soldiers, a potters field with seventeen thousand graves, a section for former slaves, a Jewish section, and even a marker for Tweet the Mockingbird. There was so much grand Victorian funerary architecture as to put Oakland Cemetery on the National Register of Historic Places.

On our way out I saw a sign pointing to the grave of Margaret Mitchell, of Gone with the Wind fame, and asked Dale if we shouldnt stop there as well.

Frankly, he said, I dont give a damn.

I forgave him that, but I surely didnt agree.

Cemeteries have long held interest for me, which may be odd given my intention to one day be cremated andnice coincidence heregone with the wind myself. Maybe this interest stems from my college years, when I sometimes mowed grass in a small cemetery in a town settled by Norwegian immigrants. Amid row after row of stones with Norwegian names was a marker for one lonely Irishman named Louis Kelly, an oddity I wove into a newspaper column years later, when I discovered Shamrock, Wisconsin.

As a traveling newspaperman I often found stories in cemeteries the way political reporters find them at city hall or sports reporters find them in a gym. In Taos, New Mexico, I stood at the grave of Kit Carson, whose frontier exploits had intrigued me as a child. In Key West, I went early one morning to the historic cemetery where the dead are buried both above and below ground to see the monument to the U.S.S. Maine and the famous headstone of B. P. Pearl Roberts, who was said to have been a hypochondriac. Her husband ordered a marker that read, I told you I was sick.

In Savannah, Georgia, visiting Bonaventure Cemetery was as much a must-do as trying the southern specialty called she-crab soup, and its hard to say which I savored more. Bonaventure is the gorgeous, atmospheric burial place made widely famous in John Berendts Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, but it had been discovered long before that. John Muir, after five days camping there in 1867, declared it so beautiful that almost any sensible person would choose to dwell here with the dead rather than withthe lazy, disorderly living.

It might sound funny to say the dead have inspired a lot of stories for me, but its true.

In Benton, Wisconsin, in the lead mine region, I once stopped at the grave of the celebrated pioneer priest Father Samuel Mazzuchelli, whose Italian name was said to have so challenged the Irish nuns with whom he worked that they called him Father Mathew Kelly instead. Sure enough, his grave is flanked by those of several nuns with Irish names, all residents of St. Patricks Catholic Cemetery.

In the cemetery in the little town of Scandinavia, I once tried to count the number of Nelsons under grass, but I gave up when I couldnt find a story in that. In New Diggings (the name refers to digging for lead, not graves) I walked through the old Masonic Cemetery, said to be the first Masonic burial yard in Wisconsin and a reminder that rites mattered, even in the states rugged early days.

In Michigans Upper Peninsula I spent an afternoon poking through Irish Hollow Cemetery, where it occurred to me that the cemetery that survives a ghost town must be doubly haunted. And one of my favorite interviews ever, retold in this collection, came years ago in a cemetery on the Wisconsin-Michigan border, where an old-time sexton nicknamed Digger gave me the lowdown as only an old-time sexton nicknamed Digger could:

You got to be a cemetery man, he said. You got to be dedicated. You got to go with the weather. When theres snow, you know, or a goddarn rainstorm you got to be out there, you got to get that goddarn thing in the ground. If the man says the funeral is ten oclock Tuesday its ten oclock Tuesday.

Even though you are dead, you are on time.

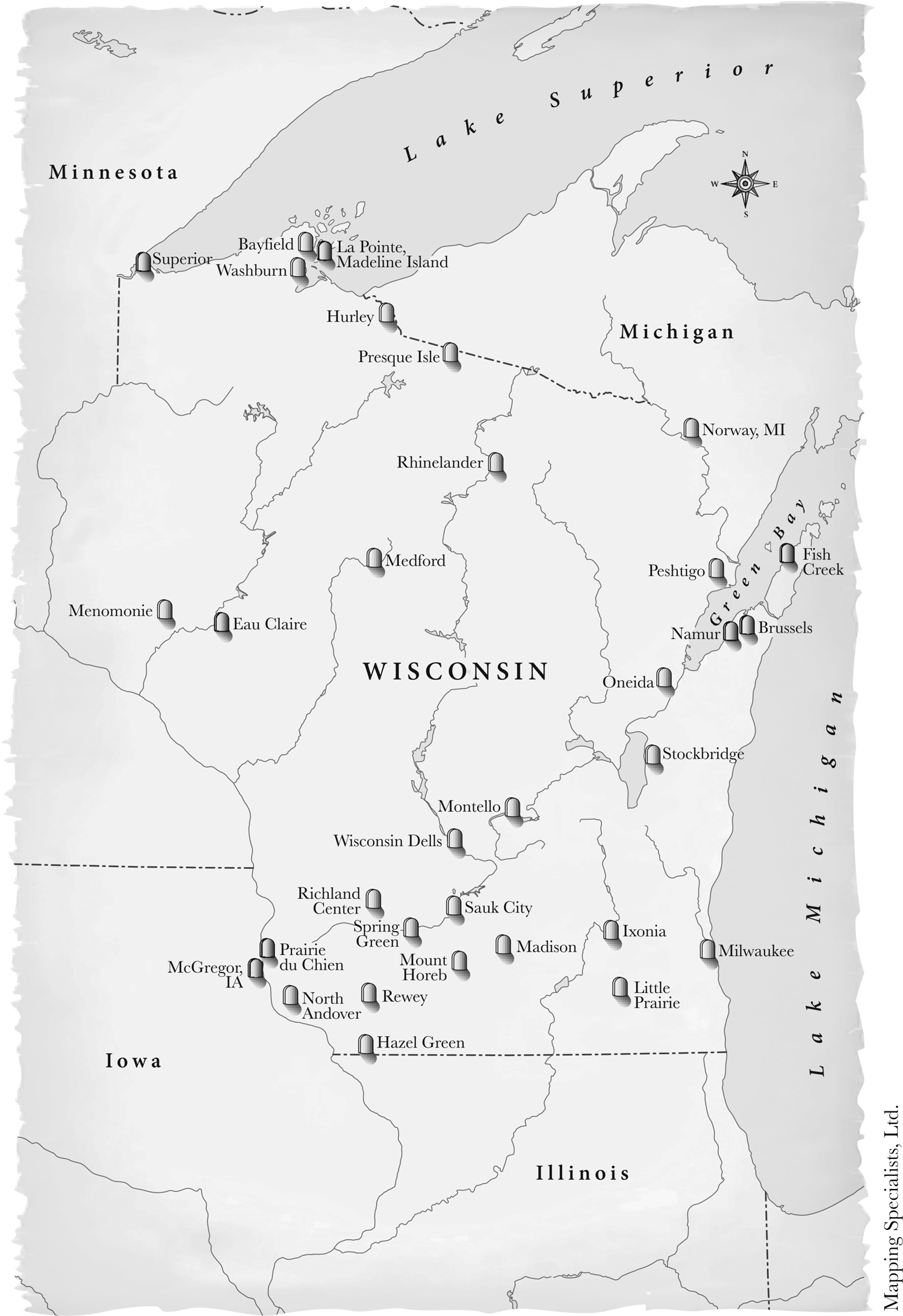

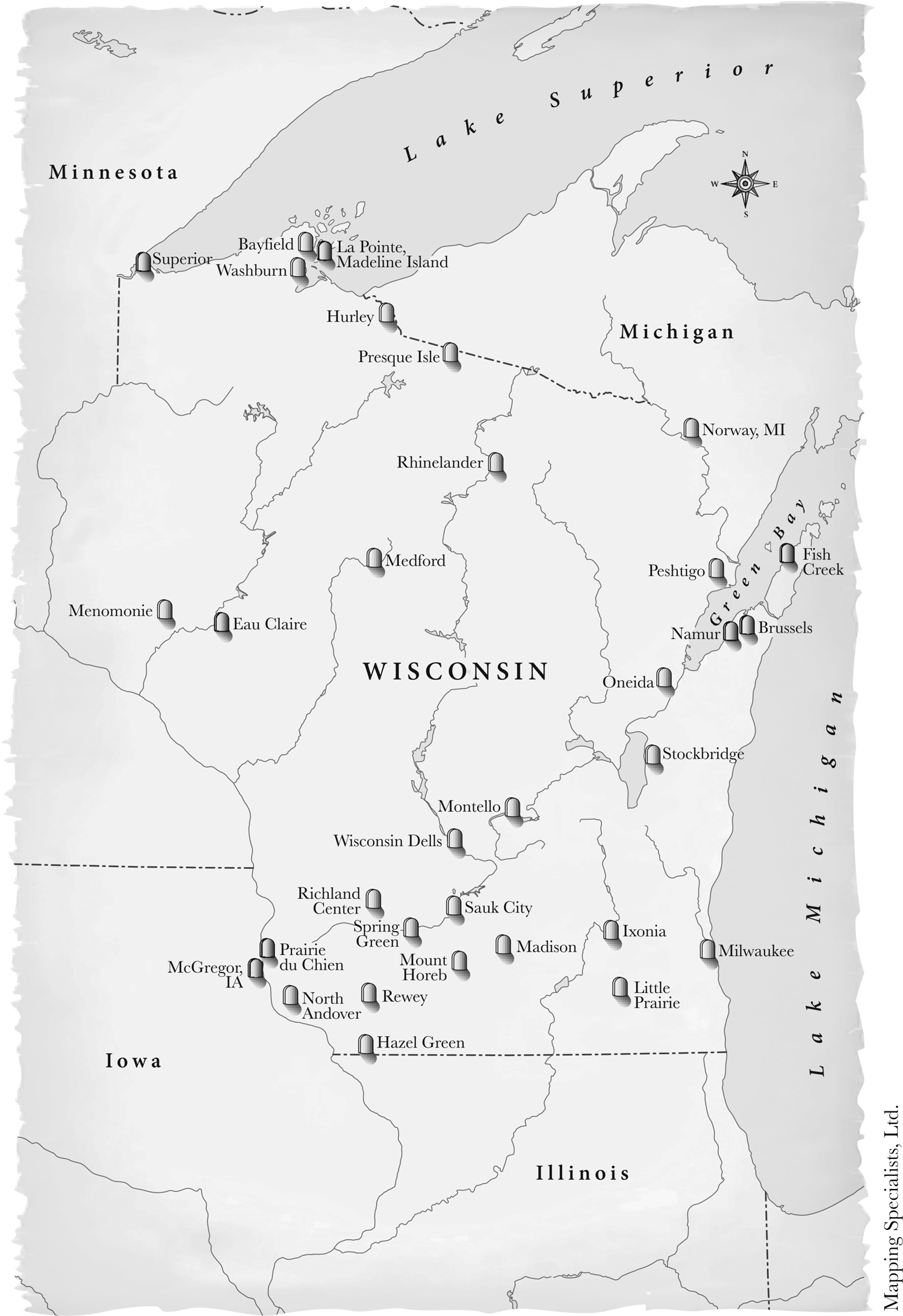

There are thousands of cemeteries in Wisconsin, large and small, tidy and neglected, so old the headstones cant tell their stories and so new the ground is still wet from the tears of mourners. For every sprawling city of the dead such as Milwaukees Forest Home Cemetery, with more than one hundred thousand burials, there is a bedroom-size family plot on a country road. In either case, and in every cemetery in between, wherever the dead rest, history lives.