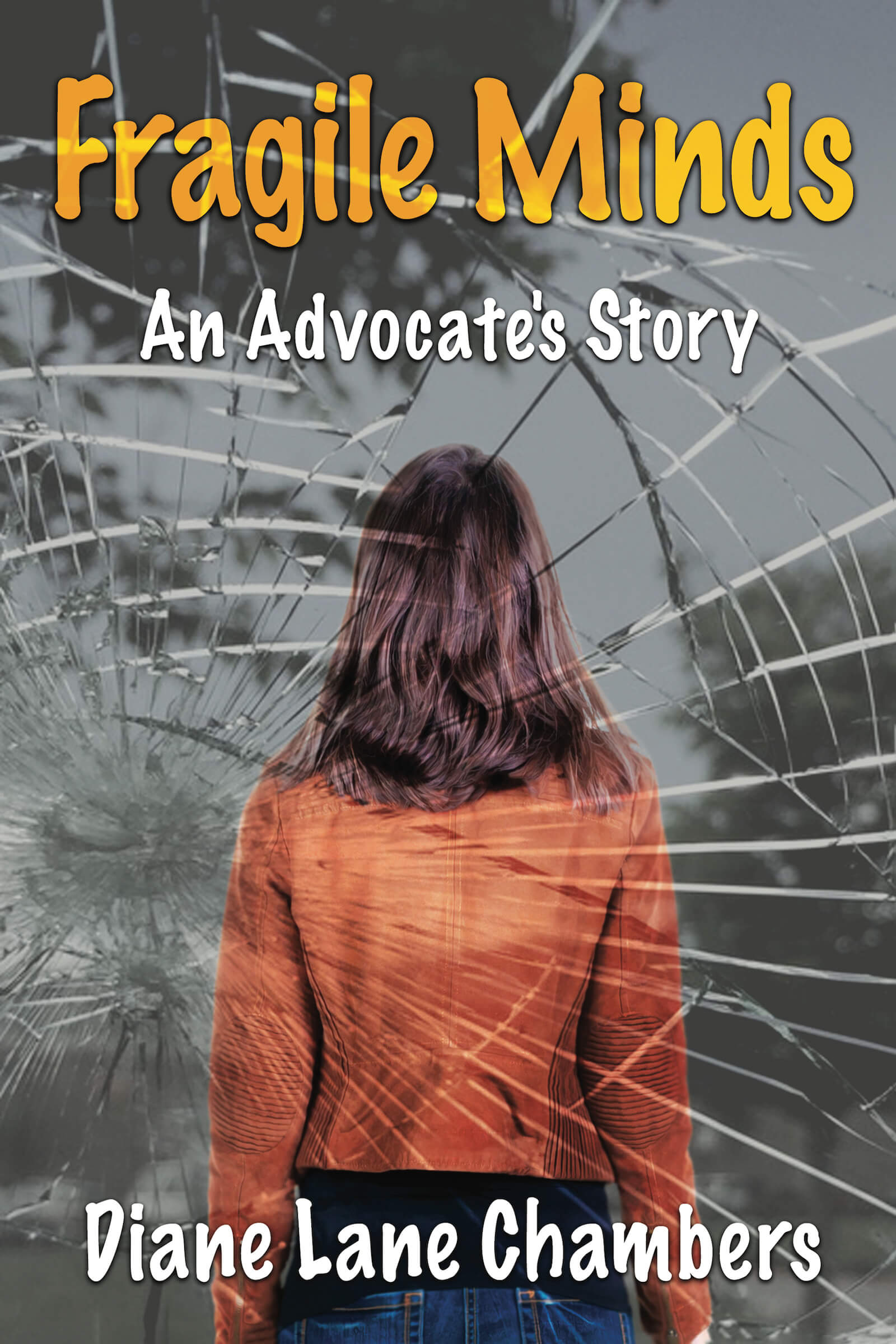

Copyright 2022 Diane Lane Chambers

Ellexa Press LLC, Conifer, CO

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by an information storage and retrieval systemexcept by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review to be printed in a magazine, newspaper, or on the Webwithout permission in writing from the publisher.

Book Design by YellowStudios

eBook ISBN 978-0-9760967-9-5

Paperback ISBN 978-0-9760967-8-8

Library of Congress Control Number 2022904133

First Edition

Freedom to be insane is an illusory freedom, a cruel hoax perpetrated on those who cannot think clearly by those who will not think clearly.

E. Fuller Torrey

Contents

Authors Note

This book is a memoir. While the story about me is true, out of respect for the privacy of others and the oath of confidentiality I have taken to practice my profession, the names, situations, and particulars of other people in this book are fictional. Where I have used real names, it has been with their permission. In addition, I have made every effort to ensure the accuracy of the academic information contained in this book. Any errors, inaccuracies, omissions, or inconsistency herein is unintentional, as well as any slighting of people, places, or organizations.

Preface

Depression, anxiety, and panic attacks are NOT a sign of weakness. They are signs of having tried to remain strong for too long.

Stuffs video, Facebook, May 27, 2017

Where does mental illness come from? Is it part of us from the beginning, brought forth from the womb, or does it fall upon us, conceived from lifes tribulations and traumas? After all, there is no routine blood test that can diagnose mental illness. Researchers say that mental illness is genetic or tends to run in families, and my family is no exception. Among my relatives there is schizophrenia and others of us who struggle with anxiety and depression.

My own struggle with anxiety and depression snuck up on me. Like so many people, I didnt recognize it until it was full blown. I was 51 years old. I knew something within me was off-kilter, but I had no clue what it was. I just couldnt sleep. I couldnt sleep because my heart would not stop pounding. I thought about going to the ER many times but never did. What would I tell them, I thought, as I lay back the seat in my car exhausted, trying to nap in between my interpreting assignments. But sleep would not come. It went like this for months. My memories are hazy of how or when it all started, but looking back on what Id been through in the four years leading up to it, its not a surprise that I eventually crashed.

Id been diagnosed with breast cancer and upon finishing treatment Id gotten involved with several breast cancer groups. I started meeting scores of women diagnosed with the disease and making friends with many, some of whom died. They lost their fight against the disease and I lost their friendship.

One of these women was my neighbor, Sue. I drove her during the snowy month of January to her chemotherapy appointment. We were breast cancer buddies. I was a four-year survivor, and she was an eight-year patient. I was writing a book about breast cancer, and she allowed me to include her story in the book. I took Sue to her appointment because she was unable to drive herself. Shed been recently hospitalized three times, and now she was afraid to drive.

Im too shaky, she said.

It was an hour-long drive to the oncology clinic from the mountains where we lived. On the way, Sue talked about her fears. She worried about how her husband would manage with their two young children if she died. She worried that her eight-year-old daughter wouldnt remember her. A few times she paused, wincing in pain from the ascites, the fluid that had built up in the sacs around her lungs. She apologized for not being talkative. She hurt too much.

At the clinic, Sue settled into a reclining chair and removed her wig. Not a hair was left on her head. She slid a soft turban over her bald head to keep warm. After her IV was hooked up, she asked me to open a can of Coke for her. She couldnt do it herself because of the peripheral neuropathy in her hands from all the chemo shed had. We talked for a while, and then she said she wanted to rest.

Id been to infusion centers before with my other friend, Harriette, whod had metastatic breast cancer for 12 years. Since I met Harriette at the Association for Breast Cancer Survivors two years before, Id been writing about our friendship and her life as an athlete dealing with metastatic breast cancer. Sitting around infusion centers with cancer patients was nothing new to me. It was something women of the breast cancer sisterhood did for each other.

In February, Sue called again, asking if I could drive her to her chemotherapy appointment. A few weeks later, when I called to check on her, there was no answer. I called again the next morning and got her answer machine. I left a message, asking her to call me back. I hung up feeling uneasy. I knew she didnt go out much. She was too sick.

That night, I was already asleep when the phone rang at 10 p.m. At that hour, I knew it had to be for something important. I sat up in bed and reached for the phone. When the caller identified himself as Sues husband, I knew it wasnt going to be good news. Id never met or spoken to him before. He was very polite, saying he was responding to my phone message. He said hed taken Sue to the hospital.

It was another episode of the fluid building up. Weve been down this road many times, he explained, But the doctor said, I cant give her any more chemo; its going to kill her. So he stopped the chemo and she just went to sleep.

Sues husband said he had gotten their two kids there just in time before she slipped away that afternoon. I fell apart after I hung up the phone, sobbing next to my husband.

At Sues memorial service, I sat in the back of the church behind all the young mothers her age who were in attendance. Many had brought their children. I cried through the entire service. I looked around at the 200 attendees, and no one else was crying like I was. Maybe theyd already shed their tears at home or they were shedding them discretely. As far as I could tell, none of them were going through tissues like I was. So why couldnt I stop crying? I thought it was about Sues eight-year-old daughter. Her big brown eyes. The innocent child and her slightly older brother, who were now suddenly motherless. It was that, but maybe it was something more.

Six months later, I participated in the Race for the Cure with my daughter and her roommate. Like many others, I wore a sign pinned on the back of my pink survivors T-shirt that said, Walking in Memory of______. Id written in Sues name.

We were supposed to be walking with Harriette and her daughter Cyndi, who used a wheelchair, but the swarms of people made it impossible for us to find them. We fell into the sea of walkers heading off to the starting line. There was no loudspeaker as Id envisioned, nor a gunshot into the air for the takeoff. It was only the people walking, a stream that soon grew into a powerful wave of people rolling peacefully along. Our energy focused up the hill ahead of us, and around the curves where bands played intermittently to keep the crowd of 63,000 methodically moving.