IMAGES

of America

CHARLES STREET

JAIL

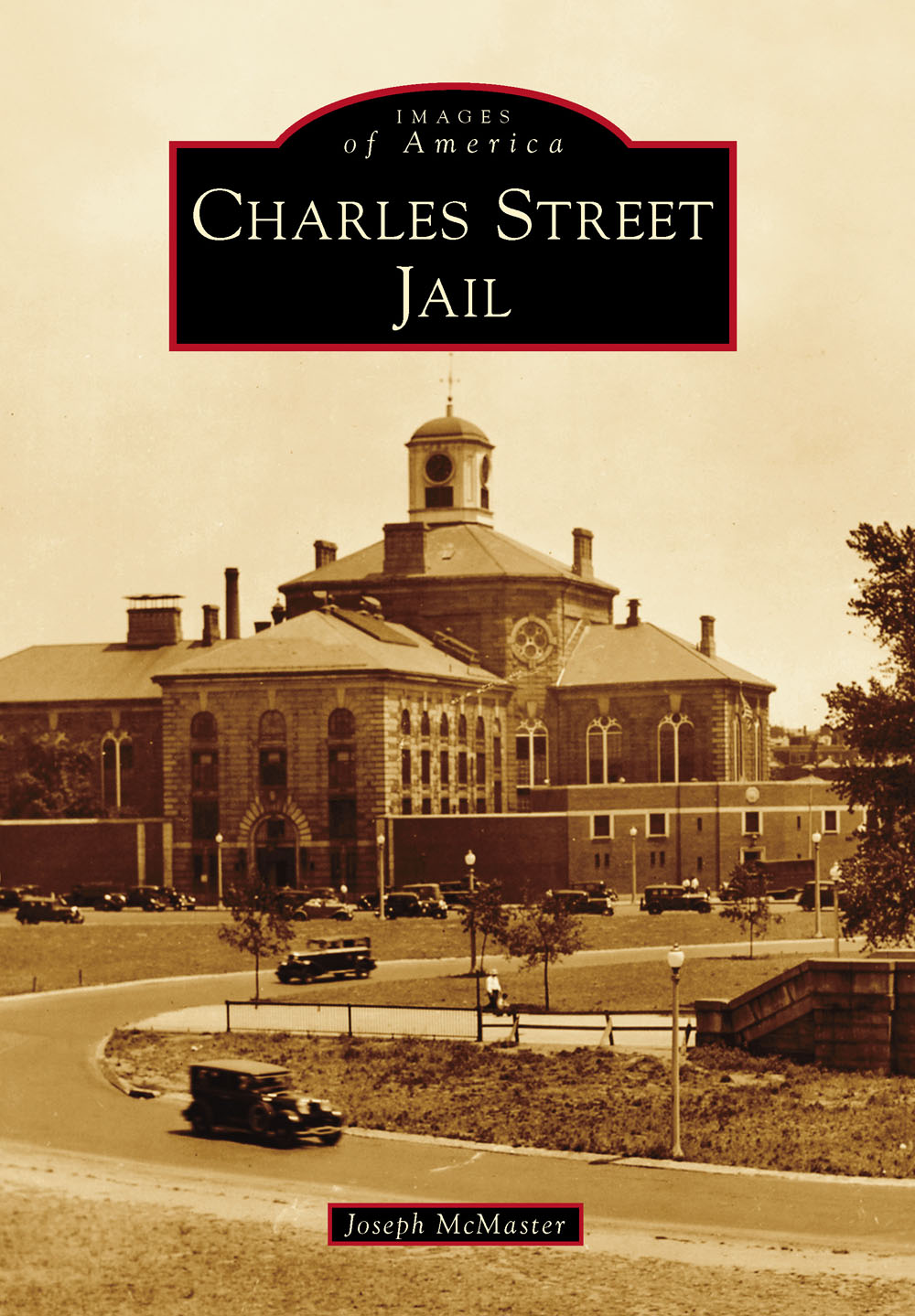

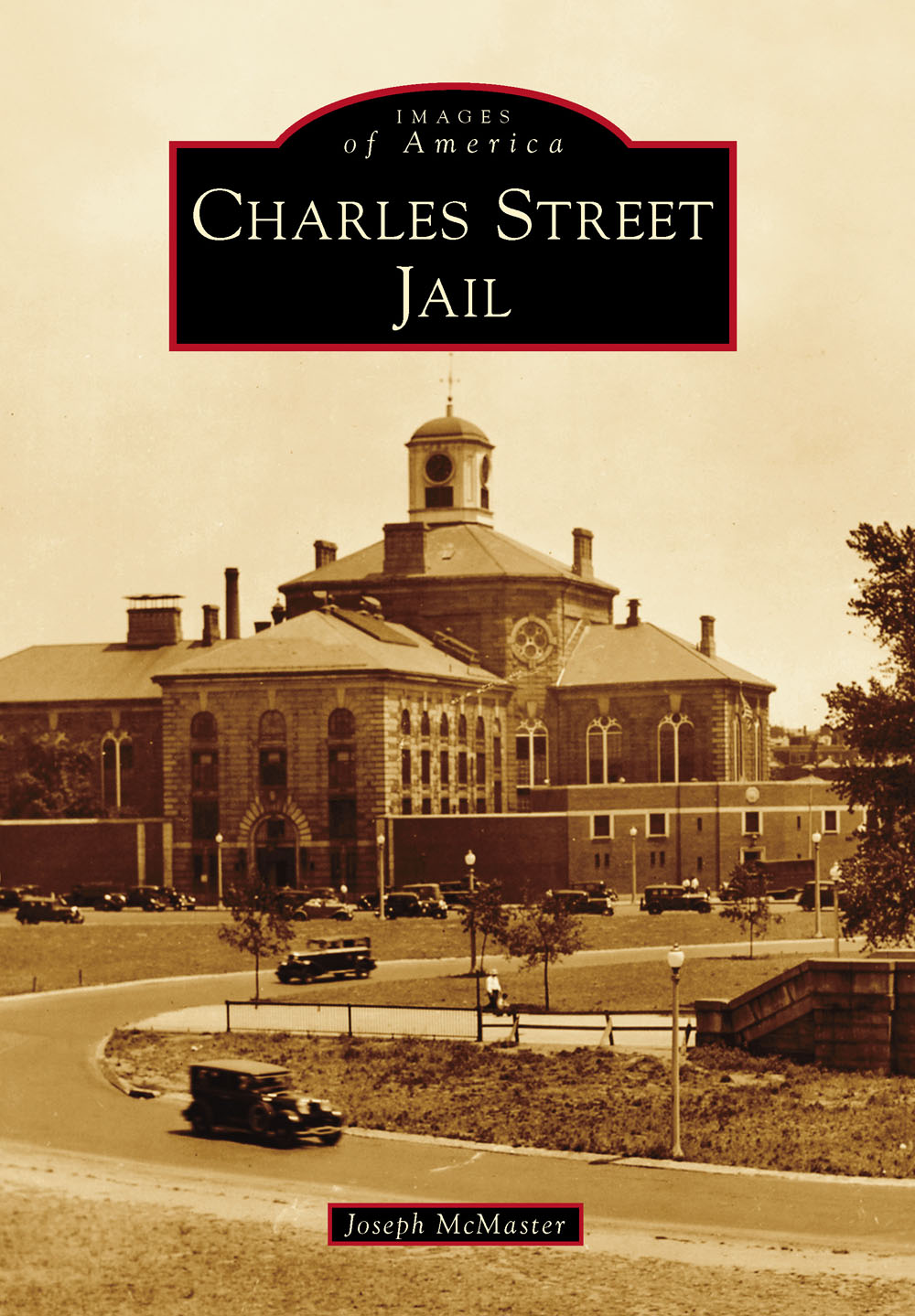

ON THE COVER: The Charles Street Jail, seen here in 1934, served as the jail for Suffolk County, Massachusetts, which includes the city of Boston, from 1851 until it closed in 1990. Today, it is a luxury hotel. (Photograph by the Metropolitan District Commission, courtesy of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation Archives.)

IMAGES

of America

CHARLES STREET

JAIL

Joseph McMaster

Copyright 2015 by Joseph McMaster

ISBN 978-1-4671-3413-2

Ebook ISBN 9781439654323

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015935772

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

To all those who worked to improve conditions at the Charles Street Jail, all those who worked to preserve and restore the building, and Gretchen and Iain for giving me the time to take this journey

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank all those who so generously gave their time and/or provided images for use in this book, particularly Arthur Pollock, the Boston Herald; Jane Winton, Aaron Schmidt, Eve Griffin, Evelyn Lannon, and Tom Blake, Boston Public Library; Sean Fisher, Commonwealth of Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation Archives; Elizabeth Roscio, the Bostonian Society; Marta Crilly, Boston City Archives; Margaret Sullivan, Boston Police Department; Richard Friedman, Carpenter & Co; Gary Johnson and Kwesi Budu-Arthur, Cambridge Seven Associates, Inc.; Suffolk Construction; the Liberty Hotel; and of course, Caitrin Cunningham at Arcadia Publishing for her patience and guidance. Photographs not attributed in the text are courtesy of the author.

INTRODUCTION

When it opened in 1851, the Charles Street Jail was hailed as one of the finest penal institutions in the country, if not the world. Boston was known for its support of social reforms, and the new jail serving Suffolk County, which includes the city of Boston, was the latest in a long list of local institutions and efforts aimed at improving society. Designed by the Boston architect Gridley James Fox Bryant and the leading prison reform crusader Rev. Louis Dwight, also of Boston, it was a grand, elegant structure built on equally grand principles. Newspapers reported that Bryant was so proud of it, he would often bring foreign visitors there and point with proper pride to what he considered his masterpiece. One 1872 report called the jail an example of the great advances which have been made in the treatment of criminals in the past few years, and praised the jail for the perfect cleanliness of the rooms and inmates, the well-prepared food, and the treatment of the prisoners as human beings.

The jails high reputation would not last, though. By 1906, the press was reporting that overcrowding was becoming a problem as two prisoners were being assigned to cells designed to hold only one. By the mid-1960s, so many problems had erupted that the jail had been investigated numerous times and was being called a malignancy on the face of Boston and a haven of political patronage and a mockery of modern penology. Finding the jails conditions so bad they violated inmates constitutional rights by amounting to cruel and unusual punishment, the courts eventually ordered the jail to close. Once an embodiment of some of societys highest aspirations, it became a stark and depressing reminder of its deepest failures.

In an ironic twist, after finally closing in the early 1990s and then lying empty and deteriorating for about a decade, the building was gutted, rehabilitated, and turned into a luxury hotel where guests now choose to pay handsomely for the privilege of staying the night. More than 150 years after it was erected, the dilapidated building at last achieved a kind of reform and redemption similar to what the jails high-minded builders hoped it would bring about in its inmates. Today, it has come full circle and is again a place that many Bostonians point to with pridejust as Gridley Bryant once did.

Richer even than the story of the rise, fall, and rise of the building are the stories of the thousands upon thousands of people unfortunate enough to spend time at the jail in its nearly century and a half of continuous use. Being a county jail and not a prison meant that most inmates at the Charles Street Jail were not convicts. Instead, they were people being heldinnocent until proven guiltywhile awaiting hearings and trials. Only a few inmates at any one time were serving longer sentences. As a result, the turnover in population was constant, and the rough granite walls were home to an unimaginably wide variety of inmates: from the most hardened murderers and thieves, to debtors, celebrities and everyday people charged with minor offenses.

If there are eight million stories in the naked city, as the movie of that name famously concludes, there must have been countless stories at the Charles Street Jail. This book presents a collection of some of the more curious, well-known, and important ones: a convicted slave trader, future mayor of Boston, notorious killers, bank robbers, social activists, wealthy eccentrics, stage stars, a famous prizefighter, gangsters, mafia members, prisoners of war, traitors, hit men, the figure thought to have inspired the famous adventure novel Around the World in 80 Days, and the infamous imposter whose book and story was turned into the hit movie Catch Me If You Can, starring Leonardo DiCaprio, to mention just a few.

Of course, alongside these colorful or memorable characters were many more whose stories have been lost to time. There were multitudes that endured harsh and unspeakable conditions, spoke up for their rights, or worked tirelessly to do their best by inmates under conditions that became increasingly difficult.

Above all, though, the Charles Street Jail building is a survivor. It was unscathed in the Great Fire of Boston of 1872, left standing when much of its neighborhoodBostons West Endwas bulldozed during urban renewal, endured decades of decline, ardent calls for its demolition, and years of disuse. And just as the building, now designated a National Historic Landmark, was painstakingly preserved, perhaps this book can help preserve some of the remarkable stories and images that surround it.

One

THE BIRTH OF THE

CHARLES STREET JAIL

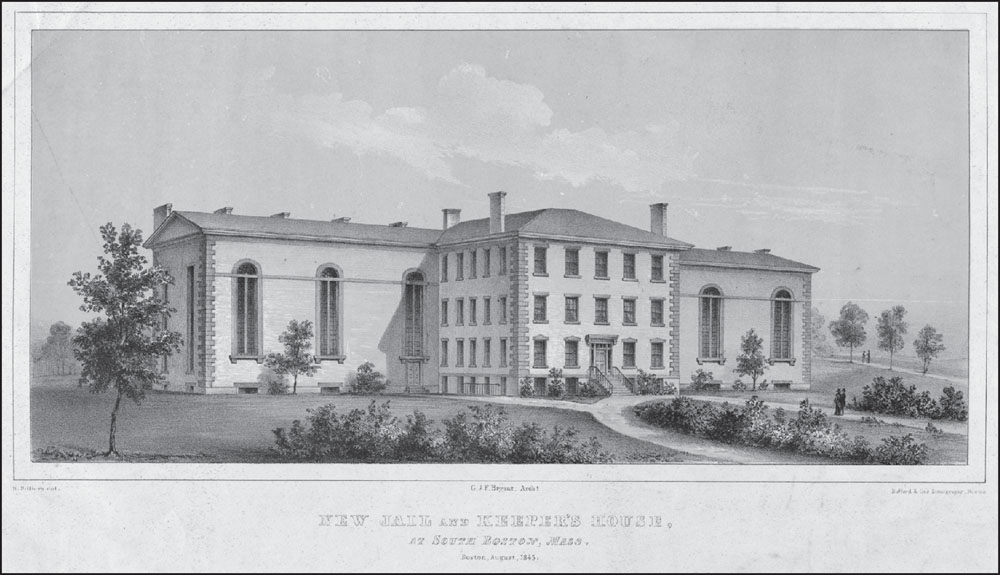

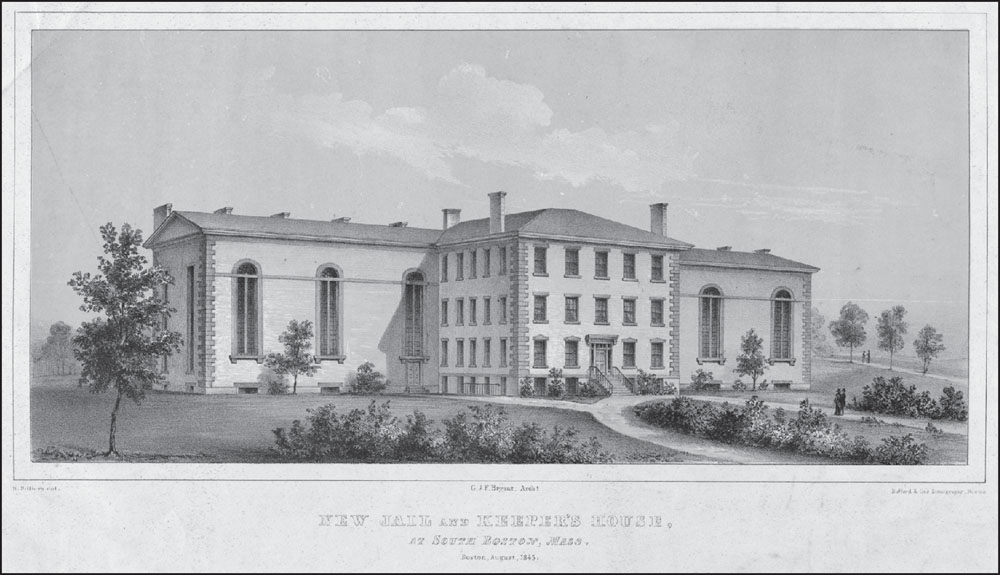

By the 1840s, the jail serving Suffolk County, Massachusetts, which includes the city of Boston, had become inadequate and out of date. When the city announced it was considering construction of a new jail, a local architect named Gridley James Fox Bryant submitted a proposal that included this rendering. Residents of South Boston opposed building the jail in their community, though, and plans for the site were dropped. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress.)

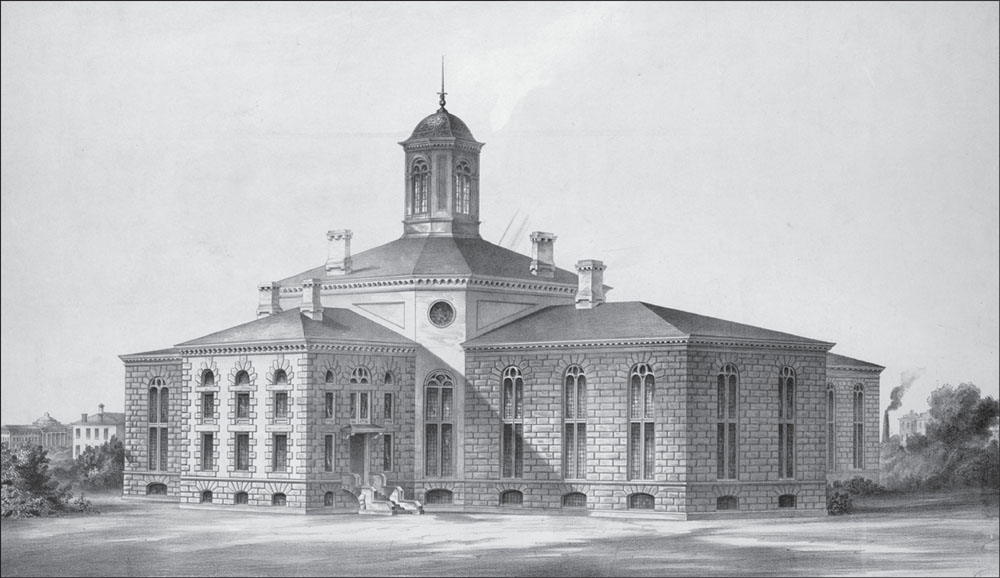

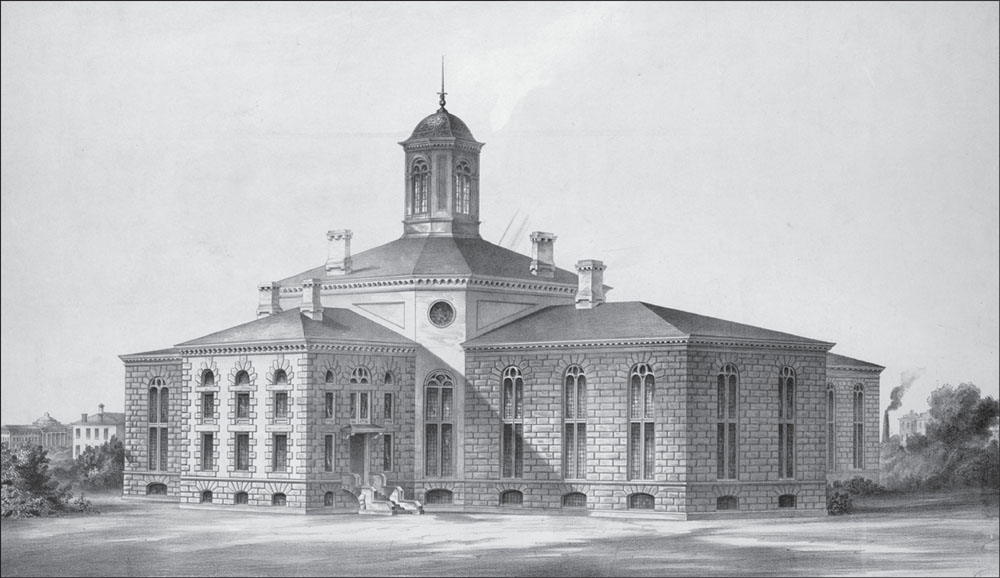

Working with a well-known prison-reform advocate and the founder of the Boston Prison Discipline Society, Rev. Louis Dwight, Bryant revised his plans and submitted this rendering for a new Suffolk County Jail in 1848. Construction began in 1849. (Courtesy of the Boston Public Library.)

Next page