Contents

Guide

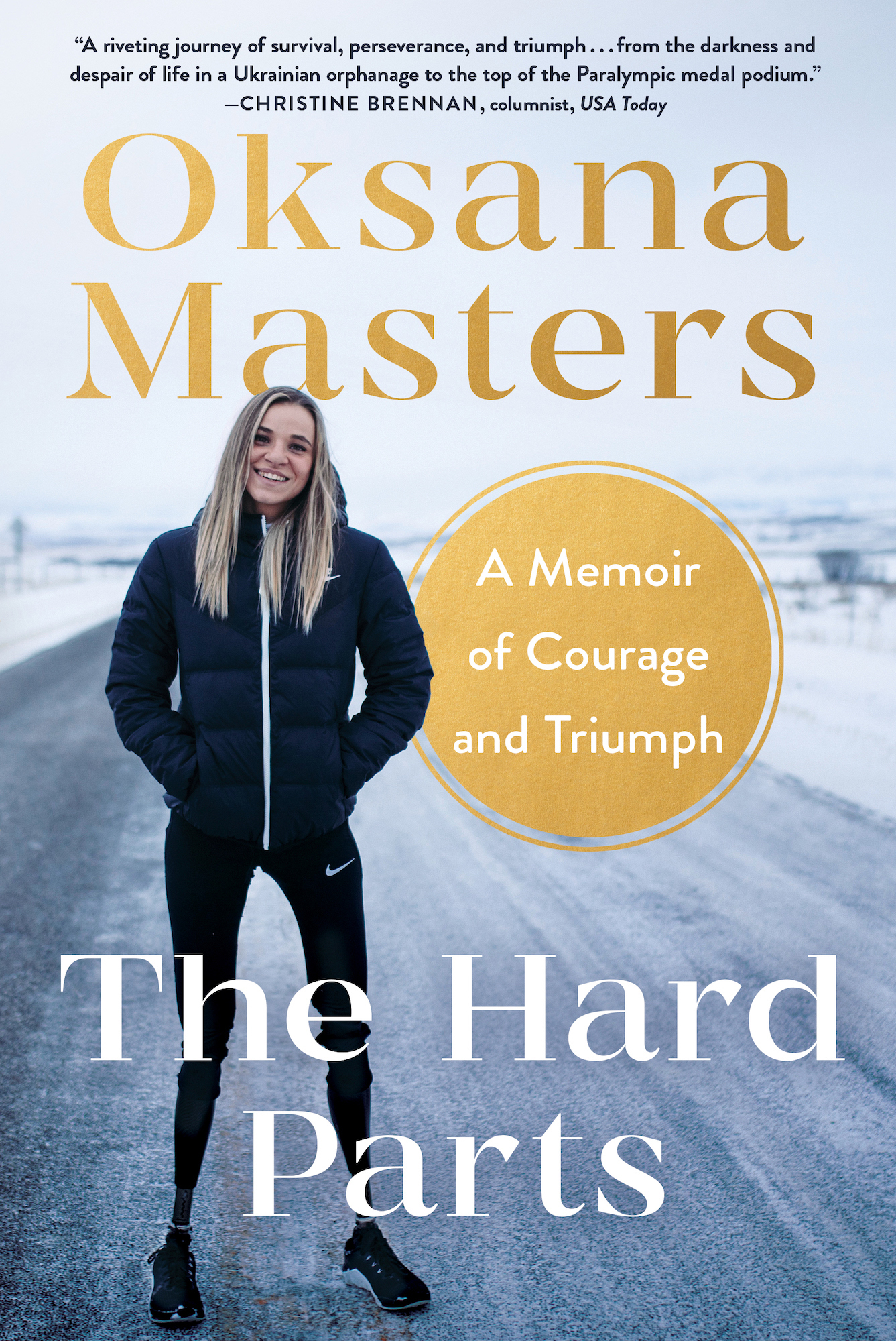

A riveting journey of survival, perseverance, and triumph from the darkness and despair of life in a Ukrainian orphanage to the top of the Paralympic medal podium.

Christine Brennan, columnist, USA Today

Oksana Masters

A Memoir of Courage and Triumph

The Hard Parts

For my mom, whose love saved me. Thank you for sacrificing it all to give me the world and for opening every door for me. You are my world and the beat of my heart.

I love you,

Your resilient rascal.

prologue

T his would be a four-to-eight-month recovery. For a normal person.

The doctors proclamation hangs in the air for a silent moment in the harshly lit emergency room. But as I hunch on the hospital bed cradling my newly shattered elbow in my hand, with my two prosthetic legs dangling limpdevices that require two functioning arms to remove and attach to what remains of my real legs (How am I going to do that with a broken elbow?)its obvious that Im not a normal person.

To my coach, who brought me here from the Bozeman blacktop where I slipped on black ice outside my favorite caf, the doctor says:

She cant race.

The pain in my elbow thats been searing every second with hurt blazes in a white-hot flashand at the same time my entire body deflates. Something essential and fundamental exits my chest. I cant race in the Games. Theyre only three weeks away. How did this happen? Im twenty-eight, and my entire lifepast and futurehinges on this insane moment. Everything is on the line.

In Pyeongchang in three weeks, I will, for the first time since I discovered what my body could do athletically at thirteen years old, show up as the true athlete Ive finally come to believe I am. This time, I wont have to live out of my car like I did before the Games in Sochi, trying to make my moms financesborrowed from her retirement fundlast just a little longer. This time, for the first time ever, I have real sponsors, big onesNike, Toyota, Visa, Procter & Gamblewho believe in me, too. I can begin to pay back my mother, pay all my debt. Ten years of Paralympic Games, and Ive always come in second or third. Never first. But this time. This time Im favored to sweep gold in every one of my eventsto be the first ever to bring home a gold medal in cross-country skiing for USA.

Oh, God, I think. Ill let everyone down. Im going to lose it all. Im eating salt from the tears pouring down my face. Grief already claims my body in waves, filling up the space of what flew from my chest, which I now realize was hope.

Anyone else would have quit by now. This is probably a sign that I should have, too. Every part of my life before this has also been decided for mewhy not this? My mind and my body were both already determined by others from the time I was born: what I was capable of doing or what was possible for me in the future. I was told I didnt deserve a mother, didnt deserve a family, didnt belong in this world. Im just too different.

Ive been told Ill never make it as an athletethat its an unrealistic, impossible goal, and that Ill only be let down ultimately. Ive been shown over and over that I have no voice of my ownhave no power.

Except on the start line.

The start line is always a fresh beginning. Nothing has been determined yet. When the clock starts and the red dot turns to green and the high-pitched beep sounds, I begin my new journey. In a race, Im in control and I am control. How I react and adapt and pivot and move. Thats all me. My strength. My power. My voice for every time I was told no, every time I was weak, every time I was pushed down. Every time I wasnt believed in, every time someone else thought they knew what was best for me.

Turning to mefinally the doctor addresses mehe says:

Its not possible. If you race on that elbow, youll never be able to use it again. This is where your road stops.

As if he knows anything about my road. Mine has never been a smooth one of clean blacktop and tidy lines. Its crooked gravel cratered in bomb holes and littered with mudslides and twisting U-turns. Was it really going to end here in a colossal explosion that blocks the way forward forever?

Maybe because of the heat consuming my arm, or because Im hallucinating a little from pain, a vision of dancing flames appears in front of my eyes, superimposed over the doctors face. Ive always loved to get lost in the flames of a fire. At backyard firepits, I stare straight into the core of the blaze, beyond the orange and yellow and the light blue and white and then down past them to the logs, at the layers it takes to create that fire.

Before the flame theres wood. Before the wood there are twigs, and before those twigs are even smaller sticks and leaves. You see a huge, roaring, strong firebut you dont see that it all started from a little tiny twig and a few leaves: things so small, fragile, breakable. And the logs on top of them. When you really look, you see the lines, the age of the tree those logs came from and what that tree must have weathered and been through.

Underneath the flaming vision flashes the trajectory of what Ive been throughmy experience in Ukraine, coming to America, what Ive seen, what Ive lost, what Ive gained, what Ive felt. It all sparked from when I was the weakest. The smallest. The frailest. When I believed I had no value to bring. It sparked from my core, with layer upon layer upon layer creating a fire that grows stronger and stronger while the flame burns longer and higher.

And I think, there on that bed with my broken body and full of my own salt and smoke, I am so tired of other people determining what Im capable of.

I.

I will decide what is possible.

part

one

chapter

one

B link.

The room is so hot and steamy and close, like a womb. The astringent, cloying smell of heated chlorine hangs in the air. I float in the hot water, blowing bubbles in it, pretending to be a sea animal. The chemicals leave my lips tingly, and I almost forget that my body hurts from whatever the latest surgery was. A woman helps me float, her hand spanning my tiny belly, her short dark hair glowing in the dim room, maybe burnished from candlelight. I cant remember what lit the chambers darkness, but I see clearly her round face, that hair, her dark features. Shes always here in this hot room, in this perfectly square pool, helping me after surgeries. She gently sets warmed glass balls on my back for some kind of therapy. She rubs my small back where the balls heat the skin. In that chlorine-musked sauna, I am happy and loved.

Maybe shes my mother. Shes the only one who touches me, offers any affection. She must be. Im so safe here.

Blink.

Down in the basement, I scrub socks against the washboard and wring them out. After I wash ten socks, the grimy old woman whos one of the laundry ladies produces a sugar cube and places it in my hand. I love sugar. But Im also so, so hungry, and Ill wash all the socks in the world for another sugar cube. Ive learned to make them last for hours. I break off individual sugar crystals with my tongue. That way, by taking so long to eat, I trick my body into feeling full. I reach for more socks and the laundry lady smiles. Maybe this woman is my mom.

one

one