James Gardner asserts his right to be identified as the author of thiswork. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrievalsystem or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permissionin writing of the publisher.

NOTES ON SOURCES

This is a true story. In order to recreate the atmosphere of the time Ihave extensively used contemporary newspapers. To avoid constantly quotingsources I have on occasion paraphrased articles.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First and foremost, I would like to thank my brother, Steve Gardner, forhis invaluable help and support in the writing of this book. He read variousversions over a long period of time and I am very grateful for his insightfulobservations. Many thanks also to the following people who kindly read themanuscript and contributed helpful criticism: Ami Bahia ,Vic Baynes , Helen Devaney ,Roger Gardner, Dr Peter Jackson and Mike Liardet ,Erika Macdonald, Cliff Pilchard and Umi Sinha . I am also grateful to Dr Rudolf Muhs ,of the London Royal Holloway University, for his historical advice aboutGermans in England during that period. Special thanks to Suzi Mehmed for proof reading; toElizabeth Mandeville for editing; to Jackie Worpe fordesigning the cover and finally to Mike Liardet againfor his assistance in its production. I am also indebted to the staff atthe London Metropolitan Archives, the Metropolitan Police Museum and theNational Archives at Kew for their assistance.

INTRODUCTION

Londonin the 1860s has been compared with the London of the swinging 1960s. Thecontemporary writer and social commentator, George R Sims, has described thecity during that period as free and easy with no grandmotherly government. Simsremembered a city dimly lit with lights which flickered in every breeze, themuddy broken roadways, the ramshackle cabs, the lumbering buses jolting andrattling over the stones and every bus inside strewn with dirty straw with thesmells of sewage and smoke emanating from every part of the city.

It was a time when bars and saloons oftenstayed open till three or four in the morning; when people drank without fearor reproach which dominated the late Victorian era; when long after midnightcertain streets of the West End and notably the Haymarket were packed with aroistering mob. But the rowdy London night life of the 1860s was not confinedto the West End. It could also be found in the dens of the desperately poorEast End with houses so close together that even a sunbeam could not force itsway between the overhanging parapets with any chance of getting to the ground.The police would only venture into their alleyways and narrow streets in twosand three.

Mid-Victorian London was also full ofbarefoot street urchins, beggars, and the homeless sleeping on benches andunder archways. Huddled together for warmth in winter, stealing their dailybread, they were everywhere. It was a time when many women and girls had toprostitute themselves just to survive. However, despite the poverty, London wasfull of music and Sims remembered that the German bands performed in streetand square at all hours of the day and night.

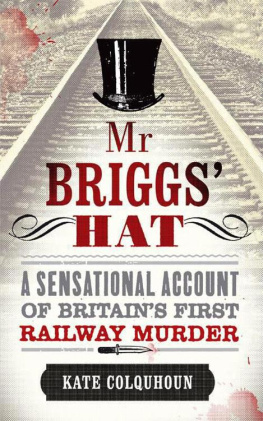

For all the nostalgia Sims had for Londonin the 1860s, he did admit it was a dangerous city to live in and that mostrespectable middle aged and elderly men carried a life preserver a shortstick with a heavily loaded end when they travelled .Compared to other means of transport, trains were considered to be more adanger to health than anything else, with social reformers such as Lord Shaftesbury blaming railway travel for the big increase inmental illness. Accidents too on the railways had created apprehension in thepublic mind.

Although violent attacks were rare, thesingle compartment system, without any communication corridor or cord, didexpose innocent travellers to drunken and immoral behaviour between stops which they could do little about.On one occasion, a young eighteen year old woman was forced to escape out ofthe door after being indecently assaulted by another passenger. Luckily, whilstprecariously perched on the footboard, she was held around the waist by anotherpassenger until the train stopped. However, many believed that the realdanger of railway travel lay in the bright new London stations where thecongregation of people made an ideal target for organized gangs of pickpockets.Actual murders on trains was considered to be a Continental sickness,particularly in France, but onJuly 9th 1864 this was about to change.

CHAPTER ONE

That Saturdaymorning, a well-dressed elderly man wearing a black silk chimneypot hat lefthis home, a large Regency townhouse in fashionable Clapton Square. He walked toHackney Station and took the train to Fenchurch Street, the first railwaystation to be built within the City of London. From there he went to Messrs Robarts & Co bank in Lombard Street where he was chiefclerk. Leaving work at 5pm he travelled by horse-drawn omnibus to the house ofhis niece Caroline Buchan, in Peckham. After dining with her, he kissed hergoodbye and was escorted by her husband, David, to the Old Kent Road where hetook a horse omnibus to King William Street. Crossing over into Eastcheap , he arrived at the impressively arched windows ofthe twenty year old Fenchurch Street Station. The evening was overcast andhumid.

Passingunder the giant clock on the faade, he showed his ticket to the ticketinspector, Thomas Fishbourne , who was sitting on hisstool eating a cheese sandwich at the foot of the steep stairs to the platform. Fishbourne recognised the portly, dignified figure asone of the regular commuters on the North London Railway line. He marked histicket and the man quietly said goodnight. The passenger entered a firstclass compartment in carriage 69 and sat in a near-side corner seat with hisback to the engine. Running five minutes late, with clouds of smoke belchingfrom its tall chimney, the 21.45 to Chalk Farm rumbled slowly out of thestation.

Fifteenminutes later the train arrived at Hackney after stopping at Bow and HackneyWick [also known as Victoria Park]. Two young bank clerks, Henry Vernez and Sydney Jones, got into an empty first classcompartment. Jones saw a black leather bag on the left hand seat nearest thedoor and flung it onto the opposite seat. Sitting down, he complained his seatcushion was wet and sticky. Looking at his hand under the dim light of thecarriage oil lamp, he was horrified to find it smeared with blood. A momentlater his companion felt something wet on the seat of his trousers and shoutedTheres blood on my seat as well! They immediately alighted and called thetrain guard, thirty-eight year old Ben Ames. He took one look at thecompartment and rushed off to get a hand-lamp from his brake van

On his return, the first thing thatcaught Ames eye was a crushed, shabby black hat lying on the floor. Thediscarded black leather bag was on a seat, blood smeared over its brass lock.Peering below the seats, he found a silver topped walking stick with blood onits tip. Fresh blood was also trickling down one of the near-side windows andthe stain of a bloody hand marked the internal and external handle of theoff-side door. He picked up a cushion. Blood had pooled in its buttonedindentation and was smeared along its edge as if someone had wiped their handson it. It was clear that there had been a violent assault but there was no signof the victim or victims. Ames took out the hat, bag and stick, locked the doorand, before sending the train on its way, asked a colleague to telegraph thenews to the Chalk Farm terminus.