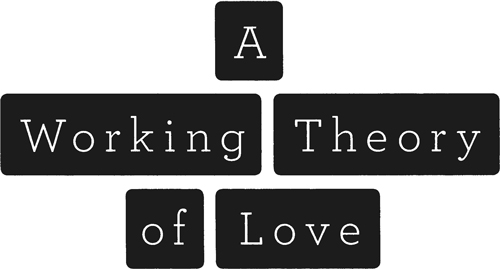

S COTT H UTCHINS

THE PENGUIN PRESS

New York

2012

THE PENGUIN PRESS

Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Copyright Scott Hutchins, 2012 All rights reserved

The Essential Turing: The Ideas That Gave Birth to the Computer Age, edited by B. Jack Copeland (2004). By permission of Oxford University Press.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA

Hutchins, Scott.

A working theory of love / Scott Hutchins, p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-59420-505-7

1. Artificial intelligenceFiction. 2. Divorced menFiction. 3. Fathers and sonsFiction. 4. Man-woman relationshipsFiction. 5. Interpersonal relationsFiction. 6. San Francisco (Calif.)Fiction. I. Title.

PS3608.U84W67 2012 813'.6dc23 2012018341

Printed in the United States of America

DESIGNED BY AMANDA DEWEY

Acknowledgments

THIS BOOK COULDNT HAVE BEEN finished without the Stanford Creative Writing Program. Particular thanks go to the committed support of Eavan Boland, Adam Johnson, Elizabeth Tallent, and Tobias Wolff, as well as Tom Kealey, Shimon Tanaka, and Malena Watrous. I am also indebted to Dan Colman of Stanford Continuing Studies for his friendship and occasional shield.

The book has benefited in untold ways from the sharp eyes of friends. I name them with outsized gratitude: Andrew Altschul, Peter Ho Davies, Skip Horack, Eric Puchner, Glori Simmons, and Jule Treneer.

A writer in need of stiff bucking up could find no better allies than from his Ann Arbor days. Special thanks go to Charles Baxter, Nicholas and Elena Delbanco, Valerie Laken, Eileen Pollack, and Lynne Raughley.

Thanks to my father, who never asked what I was going to do with my English major. And to my brother Michael Hutchins for his fiery belief. Thanks, too, to my brothers Joseph and Mark.

Im indebted to John McCarthy, the storied researcher and teacher at Stanford, a few of whose innovations Ive attributed to Henry Livorno. Even toward the end of his life Professor McCarthy was willing to talk on the phone to an unknown writer. Thanks to Hugh Loebner for hosting me as a judge for his annual Turing test, as well as to Rosalind Picard for her wonderful book, Affective Computing.

Thanks to the Cit Internationale des Arts for time and space.

Thanks to two of the finest readers and advocates I could hope to know: my agent, Bill Clegg, and my editor, Colin Dickerman. Additional thanks to Ann Godoff, Scott Moyers, Tracey Locke, Sarah Hutson, Mally Anderson, Kaitlyn Flynn, and everyone else at The Penguin Press. Special thanks as well to Shaun Dolan, Raffaella De Angelis, Tracy Fisher, Cathryn Summerhayes, and Anna DeRoy at William Morris Endeavor.

To Eli and Gaby Loots, Gawain Lavers, and Brandon and Amie Tyler for storing my stuff. Only the best of friends would.

Finally, to Shikha Hutchins, my first and last reader, who came into my life when I least expected such good fortune. Thanks for the belief, the happiness, the love. Thanks for saying yes.

Shikha

The question which we put earlier will not be quite definite until we have specified what we mean by the word machine. It is natural that we should wish to permit every kind of engineering technique to be used in our machines. We also wish to allow the possibility that an engineer or team of engineers may construct a machine which works, but whose manner of operation cannot be satisfactorily described by its constructors because they have applied a method which is largely experimental. Finally, we wish to exclude from the machines men born in the usual manner.

Alan Turing

A FEW DAYS AGO, A FIRE truck and an ambulance pulled up to my apartment building on the south hill overlooking Dolores Park. A group of paramedics got out, the largest of them bearing a black chair with red straps and buckles. They were coming for my upstairs neighbor, Fred, who is a drinker and a hermit, but who Ive always held in a strange esteem. I wouldnt want to trade situations: he spends most of his time watching sports on the little flat-screen television perched at the end of his kitchen table. He smokes slowly and steadily (my ex-wife used to complain about the smell), glued to tennis matches, basketball tournaments, football gameseven soccer. He has no interest in the games themselves, only in the bets he places on them. His one regular visitor, the postman, is also his bookie. Fred is a former postal employee himself.

As I say, I wouldnt want to trade situations. The solitariness and sameness of his days isnt alluring. And yet hes always been a model of self-sufficiency. He drinks too much and smokes too much, and if he eats at all hes just heating up a can of Chunky. But he goes and fetches all of this himselfsmokes, drink, Chunkyswinging his stiff legs down the hill to the corner store and returning with one very laden paper bag. He then climbs the four flights of stairs to his apartmenta dirtier, more spartan copy of minewhere he lives alone, itself no small feat in the brutal San Francisco rental market. Hes always cordial on the steps, and even in the desperate few months after my divorce, when another neighbor suggested a revolving door for my apartment (to accommodate high traffica snide comment), Fred gave me a polite berth. He knocked on my door once, but only to tell me that I should let him know if I could hear him banging around upstairs. He knew he had a heavy footfall. I took this to mean, were neighbors and thats it, but youre all right with me. Though maybe I read too much into it.

When the paramedics got upstairs that day, there was the sound of muted voices and then Fred let loose something between a squawk and a scream. I stepped into the hall, and by this time the paramedics were bringing him down, shouting at him, stern as drill sergeants. Sir, keep your arms in. Sir, keep your arms in. We will tie down your arms, sir. The scolding seemed excessive for an old man, but when they brought him around the landing, strapped tight in the stair stretcher, I could see the problem. He was grabbing for the balusters, trying to stop his descent. His face was wrecked, his milky eyes searching and terrified, leaking tears.

Im sorry, Neill, he said when he saw me. He held his hands out to me, beseeching. Im sorry. Im so sorry.

I told him not to be ridiculous. There was nothing to be sorry about. But he kept apologizing as the paramedics carried him past my door, secured to his medical bier.

Apparently he had fallen two days earlier and broken his hip. He had only just called about it. For the previous forty-eight hours hed dragged himself around the floor, waiting for God knows what: The pain to go away? Someone to knock? I found out where he was staying, and hes already had surgery and is recuperating in a nice rehab facility. So that part of the story has all turned out well. But I keep thinking about that apology. Im sorry, Im so sorry. What was he apologizing for but his basic existence in this world, the inconvenience of his living and breathing? He was disoriented, of course, but the truth holds. Hes not self-sufficient; hes just alone. This revelation shouldnt matter so much, shouldnt shift my life one way or the other, but its been working on me in some subterranean manner. I seem to have been relying on Freds example. My father, not otherwise much of an intellectual, had a favorite quote from Pascal: the sole cause of Mans unhappiness is his inability to sit quietly in his room. I had thought of Fred as someone who sat quietly in his room.

Next page