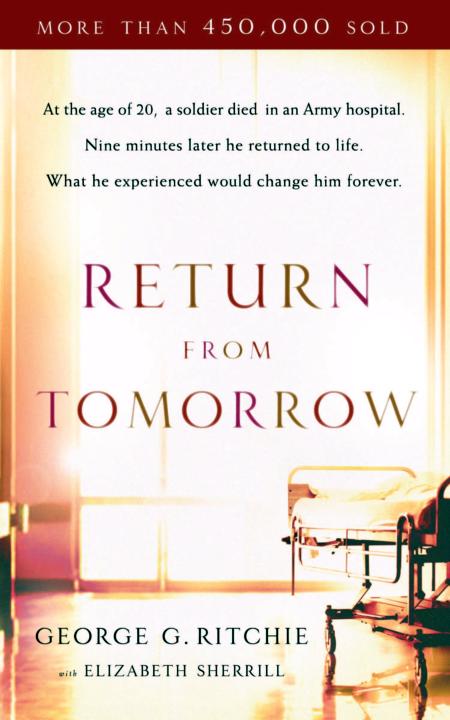

GEORGE G. RITCHIE

To His three ladies:

Marguerite Shell Ritchie, who married not only me but the experience that has governed my life;

Catherine Marshall, who first insisted I tell it all;

Elizabeth Sherrill, who helped me find the words.

All who wonder about life after death ... all who yearn to know their Savior ... all who seek the true meaning of life ... will be moved and changed by George Ritchie's encounter with Jesus, of whom he says, "Above more even than power, what emanated from this Presence was unconditional love. A love beyond my wildest imagining." Accompany George Ritchie past the boundaries of lifeunderstand the everlasting despair of hell-and glimpse with him a vision of the heavenly city. It will change you, as it has changed others.

Preface

It was a phone call from Catherine Marshall in 1956 that made me eager to meet George Ritchie. I recognized the name. I had been hearing about him for several years, ever since receiving a letter from a reader of Guideposts magazine, recounting the "incredible" story he had just heard. A certain Dr. George Ritchie had spoken at his church that morning and kept everyone spellbound with an account of his own clinical death, his resuscitation nine minutes later and what he experienced in between. Someone from the magazine should come to Richmond, Virginia, the letter concluded, and write the story.

'Incredible" is the right word, I had thought as I added the letter to my already bulging Story Leads folder. I did not doubt that the letter-writer had heard an inspiring speaker, but ... dying and coming back to report on the next world? Pretty farfetched.

I did mention the letter to my husband, John, and other editors at Guideposts, and all of us had the same reaction. Too far out!

Over the next two years the magazine received several more letters about this same George Ritchie. "I'd gone to church all my life," a 79-year-old woman wrote, "but after hearing Dr. Ritchie, I went home and committed my life to Jesus for the very first time."

That was a recurrent theme in these letters: a casual churchgoer getting serious about his faith. Scare tactics, was my guess. The fellow was probably frightening people with some outlandish tale about the fate of nonbelievers in the afterlife.

Then came the call from Catherine. Though at that time we were acquainted only through the mail and over the phone, I knew by working on her manuscripts that she was a bulldog for facts with little use for spiritual flights of fantasy.

Her voice over the phone bubbled with excitement. "I've just met the most remarkable man! His name is George Ritchie."

They had had a long conversation from which she had come away absolutely convinced of his truthfulness. "Tib, this story belongs in Guideposts! You've simply got to interview him and do an article."

Catherine was the last person on earth, I was sure, to be bamboozled by a sensation-seeker. If she felt that this Dr. Ritchie had something important to say, I was ready to listen.

At the magazine, though, the idea was again turned down. It would mean endorsing a tale no one could prove. Someday, maybe, as part of a series presenting many different accounts of deathbed visions.

In the early 1960s that day arrived. By then the whole subject of "threshold" experiences-people who, near death, believed they had had a glimpse of another world-was very much in the air. In April 1963 Guideposts began a ten-part series titled "Life after Death." For the third installment I traveled down to Richmond, Virginia, to interview George Ritchie.

Because of the impact he had on people, I was expecting to meet a human dynamo-fluent, energetic and persuasive. Instead I found myself in the presence of a tall, gentle, soft-spoken, rather reserved man of 39 with a head of luxuriant dark hair and the kindest brown eyes I had ever seen.

We were meeting in Dr. Ritchie's consulting room at his office in Richmond at the close of his workday. Though clearly tired after the long hours with patients, he was courtesy itself, holding my chair, inquiring about my comfort on the flight down, very much the Southern gentleman. In the drawl unique to that part of Virginia, he began to relate his story.

It began in December 1943 when a twenty-yearold buck private in basic training at Camp Barkeley, Texas, began to run a fever...

At 7 P.M. we broke off the interview and moved to his homestead, a substantial, redbrick, Colonial Williamsburg-style house just a mile away. There I met his wife, Marguerite, with blue eyes and light brown hair, a striking physical contrast to her husband. At dinner we were joined by their two young children, Bonnie Louise and John, after which the three adults-we were now George, Marguerite and Tib to each other-continued the interview.

Did I believe the extraordinary story George was relating? It was clear, at any rate, that he himself believed it. And after only a few hours' acquaintance, I recognized in him a scientifically oriented man, not given to imagination.

It was Marguerite's comments, though, that told me the most. George's entire life since his return from clinical death, she said, had been directed by what he had seen in those nine minutes of another kind of existence. It was from her that I learned about his work with young people, the Universal Youth Corps he had founded (which became the inspiration for the Peace Corps), his medical service without pay for those who could not afford it, his many charities, his entire life of loving and giving. Could delirium brought on by fever or drugs, I asked myself, have dominated a man's every act and decision for twenty years?

I spent the night there, and next morning George and I resumed our talks.

"Do you believe you've had an authentic preview of what awaits us after death?" I asked him.

"No," he said. "I have no idea what the next life will be like."

He had been permitted to go, he reminded me, only as far as the doorway. As for the things he had seen from there, he did not know whether he would see them after his actual demise or not. What he was sure of was that he had been in the presence of Christ, and this remained the most important event of his life.

I flew home the following day with 27 pages of notes in my briefcase. Often after an interview, there is a particular scene I cannot wait to write. In this case it was that of a young soldier walking down a corridor with another man bearing down on him from the opposite direction. He is coming too close; they are going to collide. "Look out!" George shouts. The next second the man has passed him, walking through the very space where George is standing.

George's story appeared in the June issue of Guideposts, and by July, I had received at least a dozen letters from people recounting their own near-death experiences. Every article in the series brought similar batches of mail; it proved to be the most popular series the magazine had ever run, with George's story being readers' favorite.