ALSO BY CHARLES RITCHIE

An Appetite for Life

The Siren Years

Diplomatic Passport

Storm Signals

Copyright 1987 by Charles Ritchie

Originally published in hardcover by Macmillan of Canada 1987

McClelland & Stewart trade paperback edition published 2002 by

arrangement with The Estate of Charles Ritchie

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced,

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without

the prior written consent of the publisher or, in case of photocopying or

other reprographic copying, a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing

Agency is an infringement of the copyright law.

National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data

Ritchie, Charles, 19061995

My grandfathers house : scenes of childhood and youth

First published: Toronto : Macmillan of Canada, 1987.

eISBN: 978-1-55199-681-3

1. Ritchie, Charles, 1906 Childhood and youth.

2. Diplomats Canada Biography. I. Title.

FC 561. R 58 A3 2002 327.710092 C 2001-903725-2

F 1034. R 58 A 3 2002

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada

through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program

for our publishing activities. We further acknowledge the support

of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council

for our publishing program.

My Cousin Gerald first appeared in The Anthology Anthology,

edited by Robert Weaver and published by Macmillan of Canada and

CBC Enterprises, 1984.

McClelland & Stewart Ltd.

The Canadian Publishers

75 Sherbourne Street

Toronto, Ontario

M5A 2P9

www.mcclelland.com

v3.1

To the memory of my mother

C ONTENTS

Young Charles

I NTRODUCTION

T he grown-ups who surrounded us in childhood have a special place in our memories; they linger there long after many of our contemporaries are forgotten. Children see their elders in a strange half-light of their own not at all as those elders see each other. Of course, their notions of people are influenced by their parents opinions, but they often develop a positive passion for some unlikely person and take against a family friend.

When I look back on those distant figures who peopled my own childhood, I find myself increasingly curious about them. What were they really like? What were their stories? They were an oddly assorted company, ranging from my eccentric cousin Gerald to a dispossessed Russian princess, but for the most part their roots were in Halifax, Nova Scotia, where I myself grew up.

The city in the first quarter of the century looked backward towards its former prosperity. Among my mothers friends there were nostalgic tales of the old garrison days. My mother herself had an extraordinary gift for bringing the dead back to life in her talk, so that, in my boyhood, echoes of the past were never far distant, and I did not feel too far away from an earlier Halifax, in which an older generation had lived. Theirs had been a small world, yet, small as it was, the currents of history run through all their stories. Not history as recorded in learned tomes or in the memoirs of statesmen, but history as it shaped the pattern of these different lives. From that day in August 1914 when, as a child playing on a beach, I heard of the outbreak of war, nothing was ever to be the same again for me or for any of them.

I grew up in the aftermath of that war, in the uneasy interval of peace that followed. My memories of those years are of the friends of my youth. The scenes shift from the Halifax of my boyhood to London and Paris, to Oxford and Harvard. I was following the long trail of my education from one university to another, depending on such scholarships as I could pick up, supplemented by an allowance from my mother, which she could ill afford. I was in danger of becoming a perpetual student.

When, at intervals, I attempted to find work, I was none too successful. My brief encounter with journalism only served to prove that I was no journalist. My later spell of schoolmastering, that I was not a born teacher. How lucky I was finally to come to rest on the broad bosom of the Department of External Affairs!

My friends seemed as unsettled and footloose as I was myself. Perhaps more than we realized we were the creatures of the times in which we lived: Billy Coster, the witty American cosmopolitan who killed himself with drink a tragedy of the twenties, with its atmosphere of frivolity and disillusionment; Julian Barrington, the communist son of Anglo Montreal a product of the soul-searching of the Depression thirties.

There are few famous names among those appearing in these pages. For the most part they are long forgotten, like old photographs thrown out in a rummage sale, to which no one can now attach an identity. From this oblivion I have sought to rescue them, for why should the famous be the only ones to be remembered? I can only hope that my readers will find it a refreshing change to turn from the over-exposure of public faces to these pictures of private lives.

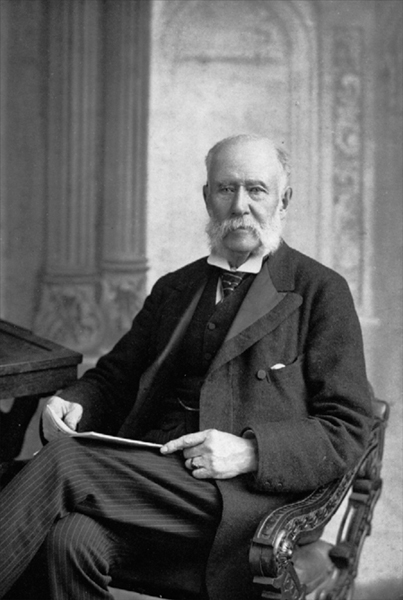

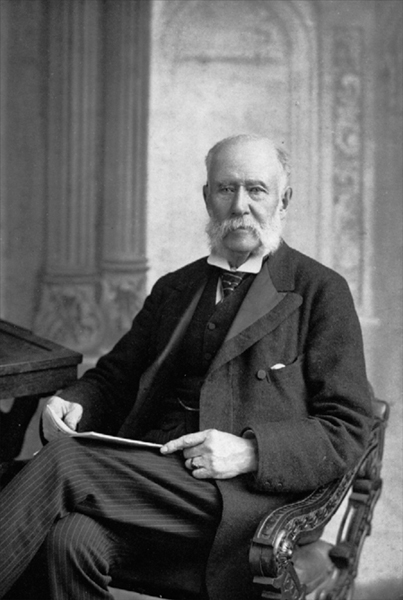

Lt. - Col. C. J. Stewart

M Y G RANDFATHERS

H OUSE

T he streets of the town were steep as toboggan slides up to the granite Citadel and down to the harbour wharves. People were accustomed to walking on the perpendicular. The houses clung at odd angles to the spine of the hill, so that a roof or a protruding upper window showed out of alignment, as in a crooked drawing. The effect was disturbing to the sense of balance. The houses were of indeterminate age some eighteenth-century, others Victorian, built of wood or stone beneath their coating of dun-coloured shingle. They were narrow houses, bigger than they looked from the front, with an air of reticence, almost of concealment. Nothing was for show. One sees such houses in Scottish towns. The poor lived in squat, bug-ridden wooden boxes, the windows sealed tight, winter and summer. A charnel whiff of ancient dirt issued from the doorways where the children thronged.

The Citadel crowned Halifax. It was flanked by army barracks built from London War Office blueprints, oblivious of climate or situation. Toy-sized cannon made a pretence of protection. Neat paths of painted white stones spaced with military precision and planted with a straggle of nasturtiums led to the officers quarters. Barracks and brothels, the one could not live without the other. The brothels were at the foot of the hill near the waterfront and the naval dockyard. One could fancy that these rickety old structures would one day collapse from the vibration of the rutting that went on within their walls. From the wharves the stink of fish was wafted up the streets and the fog rolled in from the harbour, bringing with it a salty taste to the lips. The sound of the fog-horn was the warning melancholy music of the place.