Because its fun. Its a hunt. I get a certain joy out of finding rare works, out of learning the stories attached to them.

ARMAND HAMMER,

on why he collected

INTRODUCTION

Theo Woodall first looked at his birth certificate in 1969, when he was forty-seven years old. An elderly aunt had suggested he do so. You should have been told earlier, she added. The document told Theo why. His parents, Philip and Linda Woodall, were really his aunt and uncle. Lindas sister, Theos glamorous Aunt Dorise (she had added the final e some years earlier) was his true mother. Thats the kind of news that would shake any man, but what really struck him was the name of his fatheron the birth certificate, despite Theos illegitimacyNicholas Faberg. Theos paternal grandfather had been the worlds most famous jeweler, supplier to the Romanovs and half the nobility of Europe, Carl Gustavovitch Faberg.

For the previous thirty years Theo had been a production engineer. In 1967, two years before he discovered his true parentage, he had cofounded a coil-winding firm, Theobar Engineering. It was the culmination of a technical career that had started with an apprenticeship at General Aircraft at the London Air Park in Feltham. The information on his birth certificate, however, changed everything. Within a few years Theo had sold his share of Theobar and found a new vocation as a wood turner and, eventually, jewelry designer. After reclaiming his fathers name, he died in August 2007 as Theo Faberg; his daughter, too, was born a Woodall but is now known as Sarah Faberg. Her St. Petersburg Collection is sold from a shop in Londons Burlington Arcade, around the corner from Tiffany & Co. and Asprey. Its limited edition pieces sell for thousands of pounds. As a family, theyve come a long way from coil-winding.

How can the discovery of a birth certificate make such a difference to a life? What is it about the knowledge of descent from Carl Faberg that could wreak such a change? It is not as though the goldsmiths products are universally admired as icons of good design. Some may have been copied and admired by successive generations of jewelers, but others, even the deepest aficionados would admit, are fabulously over-the-top concoctions. An elaborately decorated parasol handle or a rhinoceros-shaped match container may make you laugh, but that is no reason for the respect, even semi-deification, that their maker now enjoys.

A typical piece of Faberg is not particularly rare. Carl was no lone artisan; his workshops employed hundreds of workmen turning out thousands of objects every year. Nor is it usually the diamond-studded ornament of popular imagination. Fabergs creations may have come to symbolize the enormous wealth of his clientelethe aristocracy of Europes golden agebut they were made with relatively unexciting materials. Carved hard stones and enamel were Fabergs stock-in-trade, not fabulous diamonds or enormous rubies.

Even the name Faberg is hardly redolent of unambiguous luxury. For fifty years it has been most commonly used as a name attached toat bestmidmarket toiletries. For Britons of a certain age it is indelibly linked with a brand of aftershave, whose television advertisements, fronted by a boxer who had once knocked down Muhammad Ali, advised users to Splash it all over.

Nowadays, of course, the price of Faberg alone commands attention. It is difficult not to be impressed when an enameled silver desk clock, made in 1903 and less than five inches high, sells for $200,000 at auction. Few investments outpace inflation by something like a factor of forty. Yet price alone is no reason for respect. In the words of one modern Faberg dealer, Theres only really one price thats significant with a work of art, and thats what the patron pays; the rest is just completely ephemeral. Besides, value is surely a consequence, not the cause, of whatever makes this particular jewelers works so special.

One reason for the mystique attached to Fabergs name can be found in the sheer quality of his work. As Queen Mary, wife of Britains King George V and one of the jewelers most fervent admirers, once put it, There is one thing about all Faberg pieces, they are so satisfying. The click of a well-closed case, the perfection of a flawless surface, the sense of solidity when holding even the most apparently ethereal piece: all speak of an attention to detail and a devotion to quality that demand admiration. But Fabergs craftsmanship is hardly unique. Several of his contemporaries maintained similar standards, and there is no ripple of excitement when their fabrications appear in the salesroom.

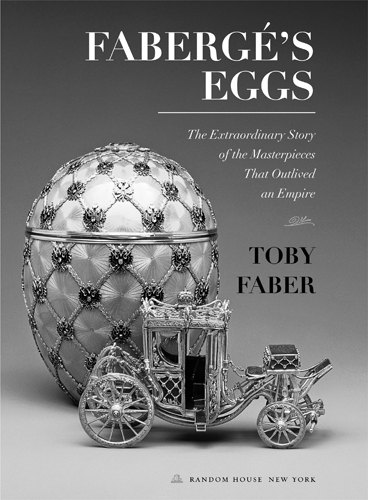

No. If there is one reason why we have all heard of Carl Faberg, it is because we have all heard of his most famous creations. He is, to put it bluntly, the egg guy, famous above all for the eggs made by his firm for Russias czars to give as Easter presents to their czarinas. In a little more than thirty years, fifty of these imperial eggs were completedeach one unique. And now their reputation is legendary, enough to overshadow all the jewelers other pieces, but also to give them lustre.

Even modern imitations benefit from the originals reflected glory. In March 2006, the story that supermodel Kate Moss smuggled the drugs ecstasy and Rohypnol in a 65,000 gem-encrusted Faberg eggclearly a replicamade headlines around the world. And the St. Petersburg Collections most sought-after products, by far, are its eggs, notably those designed by Sarah Faberg to celebrate footballers such as Jimmy Johnstone and George Best.

As for the original imperial eggs, each tells a story. Their individual designs inevitably reflect something of what was then happening in the lives of the czarinas. Fabergs relentless search for novelty, for something that would interest his royal Romanov patrons, makes certain of that. And, since the fall of the czar, the eggs have accumulated anecdotes. They have been smuggled past border guards, been used to repay favors among Communist sympathizers, and been stolen from an exhibitiononly to be recovered months later in a high-speed car chase. Most tantalizing of all, perhaps, are the eggs for which there is no history, those that disappeared in the revolution or soon afterward. They raise the possibility, however remote, of eventual discovery, of the classic attic treasure trove. It is no wonder that in films from Octopussy to Oceans Twelve a Faberg egg has acted as immediate shorthand for desirability, glamour, and intrigue.

As a group, too, the overall history of the imperial eggs is equally fascinating. Whether fairly or not, their opulence and occasional vulgarity mean they have come to symbolize the decadence of the court for which they were made. Now I understand why they had a revolution is the common remark of someone viewing these creations for the first time. They may be masterpieces, but they also embody extravagance that even the Romanovs most ardent supporter would find hard to justify. After 1917s inevitable cataclysm, the eggs disappeared in the chaos of the times. Most eventually emerged, carefully preserved in the Kremlins vaults, only to be earmarked for sale in Europe and America by Communists eager for foreign exchange. Since then they have been bought and sold by monarchs, entrepreneurs, and collectors. And they have acquired a new status: immensely personal, yet gloriously flamboyant, they have become perhaps the most tangible surviving symbols of the last czar and his family, and of the gilded lives they led before their final tragic end in a Siberian basement.