MOSCOW STATIONS

Venedikt Yerofeev, who was born inside the Arctic Circle in 1938 and died in 1990 of throat cancer and a lifetime of drinking, never caught the notice of that vast world known to pre-glasnost Russia as abroad. Unlike Solzhenitsyn or Sinyavsky, or any number of other samizdat writers, he didnt seem to be saying anything of great importance. He revealed no body counts, exposed no officials and engaged in no ideological debates. Until just a few years before his death, in fact, Moscow Stations was a cult classic, a manuscript that circulated in typescript and rarely moved beyond a few major cities. The novel dramatizes society on the brink of doom, exhausted, corrupt, bewildered, but going into the night with sodden dignity.

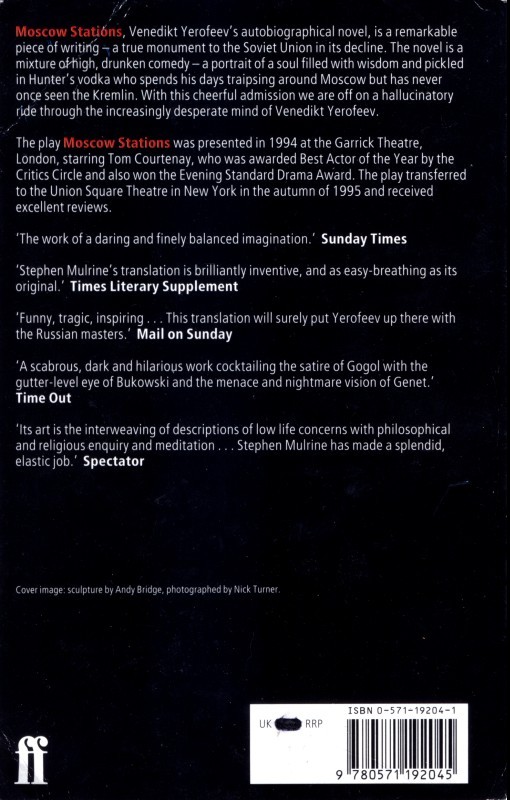

Moscow Stations, Venedikt Yerofeevs autobiographical novel, is a remarkable piece of writing a true monument to the Soviet Union in its decline. The novel is a mixture of high, drunken comedy a portrait of a soul filled with wisdom and pickled in Hunters vodka who spends his days traipsing around Moscow but has never once seen the Kremlin. With this cheerful admission we are off on a hallucinatory ride through the increasingly desperate mind of Venedikt Yerofeev.

The play Moscow Stations was presented in 1994 at the Garrick Theatre, London, starring Tom Courtenay, who was awarded Best Actor of the Year by the Critics Circle and also won the Evening Standard Drama Award. The play transferred to the Union Square Theatre in New York in the autumn of 1995 and received excellent reviews.

The work of a daring and finely balanced imagination. Sunday Times

Stephen Mulrines translation is brilliantly inventive, and as easy-breathing as its original. Times Literary Supplement

Funny, tragic, inspiring... This translation will surely put Yerofeev up there with the Russian masters. Mail on Sunday

A scabrous, dark and hilarious work cocktailing the satire of Gogol with the gutter-level eye of Bukowski and the menace and nightmare vision of Genet. Time Out

Its art is the interweaving of descriptions of low life concerns with philosophical and religious enquiry and meditation... Stephen Mulrine has made a splendid, elastic job. Spectator

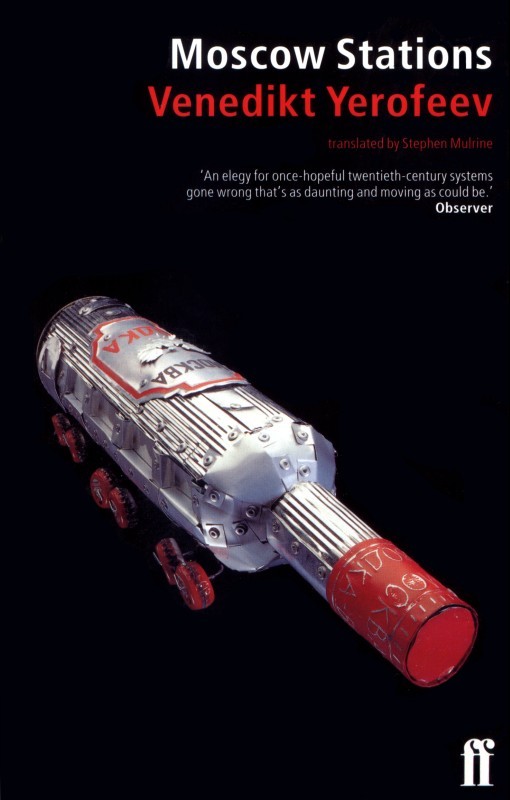

An elegy for once-hopeful twentieth-century systems gone wrong thats as daunting and moving as could be. Observer

Cover image: sculpture by Andy Bridge, photographed by Nick Turner.

Venedikt Yerofeev

Moscow Stations

A poem

translated by

Stephen Mulrine

faber and faber

in association with

Brian Brolly

To Vadim Tikhonov, my beloved first-born,

the author dedicates these tragic pages...

First published in Great Britain in 1997

by Faber and Faber Limited

3 Queen Square London WC1N 3AU

in association with

Brian Brolly

This paperback edition first published in 1998

Photoset by Avon Dataset Ltd, Warwickshire

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

Mackays of Chatham PLC, Chatham, Kent

All rights reserved

This translation Stephen Mulrine, 1997

Stephen Mulrine is hereby identified as translator of this work in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

publishers note

The first translation of Moscow Stations to appear in English was by Jana Howlett, published by The Writers and Readers Co-op under the title Moscow Circles in the mid-1980s.

Stephen Mulrines dramatization of Moscow Stations was broadcast on BBC Radio 3 and then staged at the Traverse Theatre, Edinburgh, in January 1993, starring Tom Courtenay. The present prose translation is published by Faber and Faber in association with Brian Brolly, who presented the Traverse Theatre production starring Tom Courtenay at the Garrick Theatre, London, in 1994 and at the Union Square Theatre, New York, in 1995.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP record for this book

is available from the British Library

ISBN 0-571-19204-1

Foreword

Venedikt Yerofeev was born on 26 October 1938, in Poyakonda, a small town in the far north of Russia, a treeless Arctic landscape relieved only by the watch-towers of Stalins labour camps. Yerofeevs father was the local stationmaster, with a reputation for womanizing and hard drinking. In the year of Yerofeevs birth, he was arrested for openly criticizing the Soviet power, and sent to the camps, where he remained until 1954. Yerofeevs mother, to avoid the same fate, temporarily abandoned her infant son, and Yerofeev spent his early years in a childrens home near Murmansk, of which his most lasting impression was mortification of the flesh and a cult of physical fitness.

Despite these unpromising beginnings, Yerofeev excelled at school, and in his final year won the prestige gold medal award, his passport to what he later described as that idiotic monument on the Lenin Hills, the newly built Moscow University. In an interview given in 1989, the year before his death, Yerofeev confesses that on his journey south to Moscow he saw cows and pine-trees for the first time. He also claims to have written his first story at the age of six, a work titled Diary of a Madman, but his serious literary ambitions date from his time at university, which was perhaps fortunately cut short by his expulsion midway through second year.

Yerofeev had already begun absenting himself from lectures, out of boredom, but the last straw, as far as the university was concerned, was an incident during compulsory military training, when the Major in charge of the class informed the students, standing half-heartedly to attention, that the most important thing a man could possess was a straight back. Yerofeev couldnt resist it: Those were Hermann Goerings words, he pointed out, and they hanged him in 1946!

After leaving university, Yerofeev drifted from one town to another, and in 1959 took up residence in Petushki, some eighty miles east of Moscow, selected apparently on a whim, and enrolled for teacher training at the Vladimir Pedagogical Institute. His second encounter with the academic world proved no happier than the first, and by 1962 not only was Yerofeev himself persona non grata with the authorities, but any student spotted in his company was liable to immediate expulsion. Nonetheless, in April of that year lectures at the Vladimir Institute had to be suspended while the riff-raff, as Yerofeev describes them, flocked to his wedding. His marriage to Valya Zimakova later broke up, but not before the birth of a son, who figures prominently in the novel as a focus for Yerofeevs feelings of regret.

During these years, when he traversed Russia like a latter-day Maxim Gorky, Yerofeev did a variety of jobs, including bricklayers mate, librarian, factory inspector, and cement storekeeper on the Moscow-Peking roadworks. Depending on ones point of view, Yerofeevs most bizarre employment was either as a laboratory technician in Tadjikistan in Soviet Central Asia, waging war on the local midge population, or as a police desk-clerk at Orekhovo-Zuevo, onto whose station platform his fictional ticket-inspector drunkenly tumbles. And perhaps the comparison with Gorky is more apt than it might seem, given the extent to which

Next page