DEVIL IN THE GROVE

Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys,

and the Dawn of a New America

GILBERT KING

For Lorna, Maddie, and Liv

and in memory of Matthew P. (Matty) Boylan

Contents

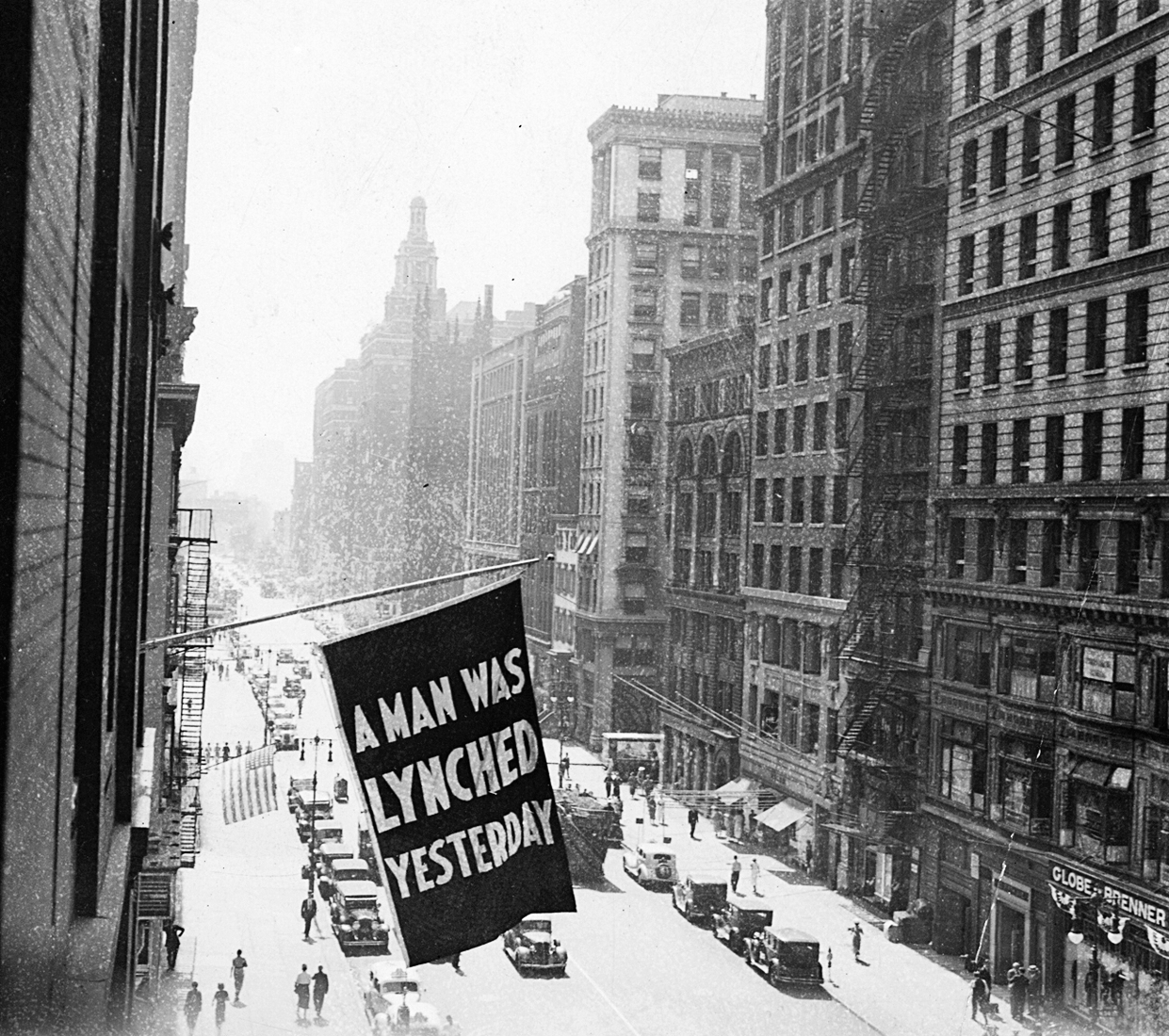

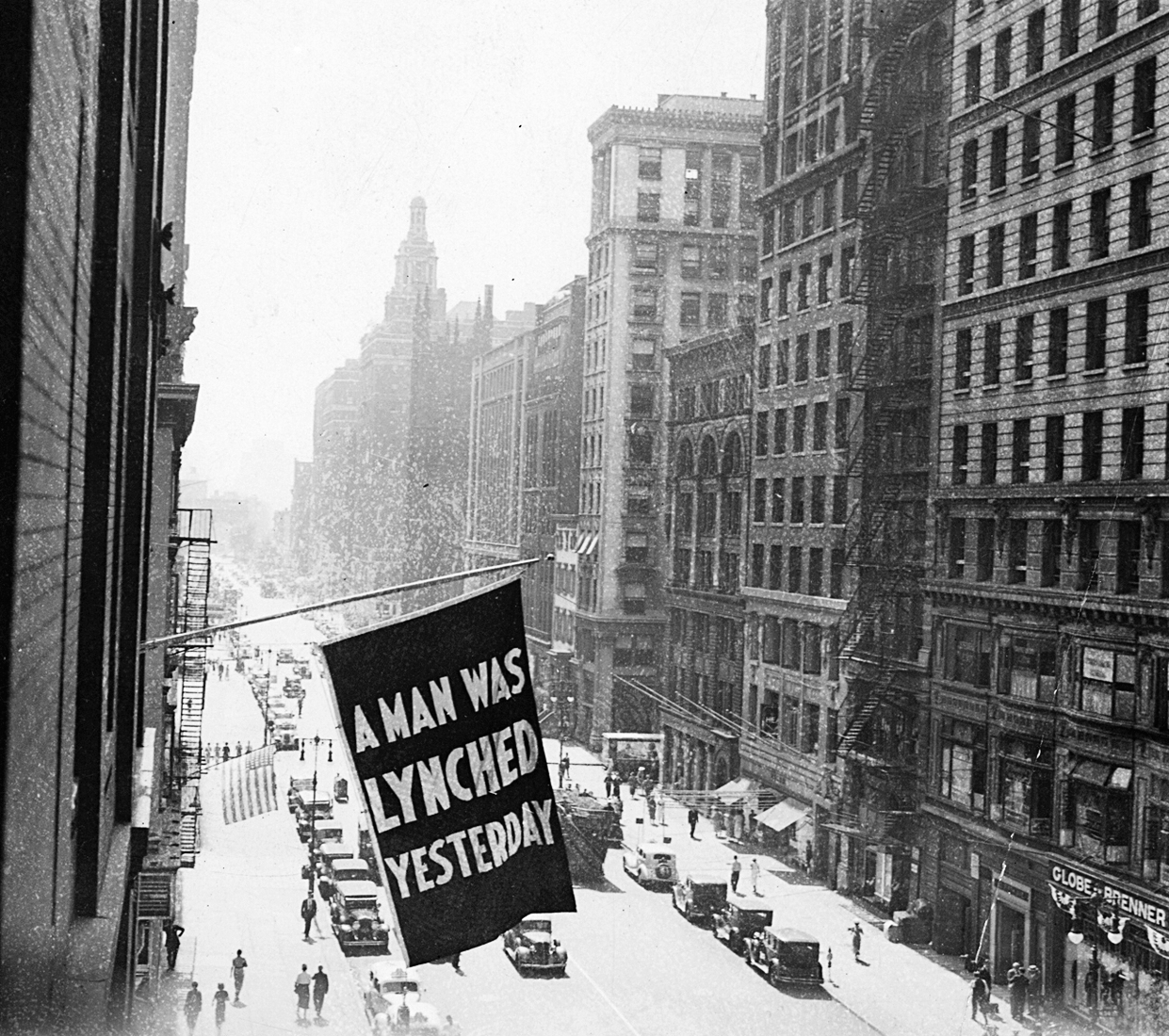

Flag outside the NAACP offices at 69 Fifth Avenue, New York City. ( Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Visual Materials from the NAACP Records )

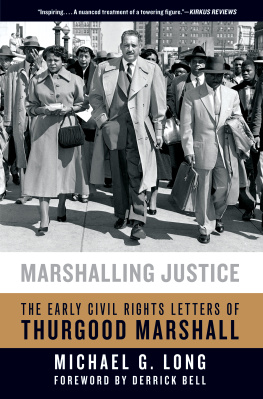

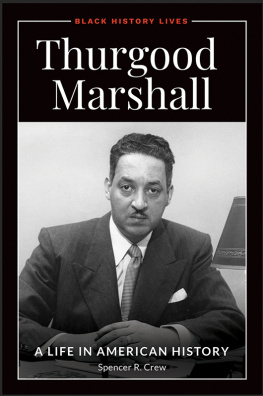

A LL HIS LIFE, it seemed, hed been staring out the windows of trains rumbling toward the unknown. Again, he was seated in the Jim Crow coach, hitched directly behind the engines, where the heavy heat bore the smell of diesel. Still, the lawyer sat proud in his smart double-breasted suit, a freshly pressed handkerchief dancing out of his pocket, as the haunting Southern landscape of cypress swamps, cotton fields, and whitewashed, tin-roofed shanties flickered by. Traveling alone, he hunched his six-foot, two-inch frame over case files; a cigarette dangling from his lips, he scribbled some notes on a yellow legal pad. He would rewrite the draft before he typed it up later; he worked meticulously. A federal clerk once told him that with just one look at the smudges or erasures on a lawyers pleading hed know if it was written by a white man or a Negro. It was a remark Thurgood Marshall never forgot. In cases like his there was too much at stake for him to be filing any nigger briefs.

The trains he rode bore grand names like the Orange Blossom Special, the Silver Meteor, and the Champion, and their rhythms ran in Marshalls Baltimore blood. Both his father, Willie, and his uncle, Fearless, had been porters on the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, and to help pay for college, young Thurgood himself had worked as a waiter in a B&O dining car. The railroads were for him and his family a source of pride, and status, but on trips like these, when he was riding alone, they also summoned in Marshall an old sadness. His wife, Buster, unable to bear the children he had longed for, had one year for his birthday given him the electric train set she had hoped someday to present to her husband and their son. With the train, and with an engineers hat perched atop his head, Marshall entertained the boys in their Harlem apartment building instead.

By the mid-1940s, Marshall, the grandson of a mixed-race slave named Thorney Good Marshall, was engineering the greatest social transformation in America since the Reconstruction era. He had already devoted more than a decade of his career to overcoming the inherent defects of a Constitution that had allowed, by law, social injustices against blacks, who had been denied not only the right to vote but also equal rights and opportunities in education, housing, and employment. With his far-reaching triumphs in landmark cases he argued before the U.S. Supreme Court, Thurgood Marshall would indeed redefine justice in a multiracial nation and become, as one civil rights pioneer described him, the Founding Father of the New America.

Before achieving those victories, however, Marshall fought countless battles for human rights in stifling antebellum courthouses where white supremacy ruled. Neither judges nor juries in the Jim Crow South had much interest in Marshalls nuanced constitutional arguments. To Marshall, the representation of powerless blacks falsely accused of capital crimes became his opportunity to prove that equality in courtrooms was every bit as vital to the American model of democracy as was the fight for equality in classrooms and in voting booths.

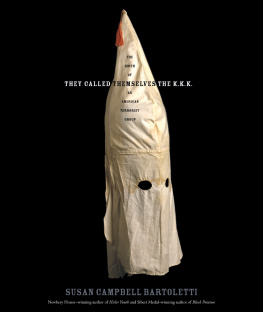

On Marshalls journeys, when the moon lit the passing landscapes of the South, he customarily drank bourbon, and he enjoyed the company of the night porterstheyd joke and talk together in segregated cars atop suitcases and the occasional casket. Or, sitting in the coach car, Marshall would drift in and out of sleep to the lullaby of the locomotive, its plaintive cry announcing every crossing as it rolled onward, southward, closer and closer to benighted towns billeting hostile prosecutors, malicious police, and the Ku Klux Klan. In the rhythm of the rails came the whipping of the wind as again the dream descended on him, and in the wind the massive black flag unfurled outside the offices of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and as a pall fell over Manhattans Fifth Avenue, he read again the message, in stark white letters on the flags flapping black field: A Man Was Lynched Yesterday.

The photographs were always horrifying: shirtless black victims, their bodies bloodied, eyes bulging from their sockets. Of all the lynching photos Marshall had seen, though, it was the image of Rubin Stacy strung up by his neck on a Florida pine tree that haunted him most when he traveled at night into the South. It wasnt the indentation of the rope that had cut into the flesh below the dead mans chin, or even the bullet holes riddling his body, that caused Marshall, drenched now in sweat, to stir in his sleep. It was the virtually angelic faces of the white children, all of them dressed in their Sunday clothes, as they posed, grinning and smiling, in a semicircle around Rubin Stacys dangling corpse. In that horrid indifference to human suffering lay the legacy of yet another generation of white children, who, in turn, would without conscience prolong the agony of an entire other race. I could see my dead body lying in some place where they let white kids out of Sunday School to come and look at me, and rejoice, Marshall said of the dream.

Seventeen-year-old Norma Lee Padgett had that lookchin held high, lips pursedwhen in her best dress she slowly rose from the witness box to identify for the jury the three Groveland, Florida, boys whom she had accused of rape. Like the sworn truth of the fictitious Mayella Ewell, the white teenage accuser in Harper Lees To Kill a Mockingbird , Norma Lees dramatic testimony against the Groveland Boys tore a county apart. Her pale index finger extended, it dipped from boy to boy as she spoke out each name, like a young schoolteacher counting heads in class, and her breathy cadence sent a chill through the courtroom.

... the nigger Shepherd... the nigger Irvin... the nigger Greenlee...

And like Harper Lees heroic lawyer, Atticus Finch, Thurgood Marshall found himself at the center of a firestorm. It would bring the National Guard to Lake County, Florida, where mob violence drove hundreds of blacks from their lives in Groveland, and in the aftermath it would prompt four sensational murders of innocents, among them a prominent NAACP executive. Despite the fact that Marshall brought the Groveland case before the U.S. Supreme Court, it is barely mentioned in civil rights history, law texts, or the many biographies of Thurgood Marshall. Nonetheless, there is not a Supreme Court justice who served with Marshall or a lawyer who clerked for him that did not hear his renditions, always colorfully told, of the Groveland story. The case was key to Marshalls perception of himself as a crusader for civil rights, as a lawyer , willing to stand up to racist judges and prosecutors, murderous law enforcement officials, and the Klan in order to save the lives of young men falsely accused of capital crimeseven if it killed him. And Groveland nearly did.

By the fall of 1951, Marshall had already filed and had begun trying in lower courts what would become his most famous case, Brown v. Board of Education , when he was again riding the rails toward Groveland. It was on such a journey to the South that one of Marshalls colleagues noticed the battle fatigue setting in on the lawyer. You know, Marshall said to him, sometimes I get awfully tired of trying to save the white mans soul. Battling personal demons as well as the devils who brought bullets, dynamite, and nitroglycerin into the Groveland fray, the lawyer saw death all around him in central Florida. So intense did the violence in Groveland become that on one of Marshalls visits, J. Edgar Hoover insisted that FBI agents provide the NAACP attorney with around-the-clock protection. Usually, though, Marshall negotiated Florida alone, despite the number of death threats he daily received.

Next page