Copyright 2013 by Jeremy Dauber

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Schocken Books, a division of Random House LLC, New York, a Penguin Random House Company, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto, Penguin Random House Companies.

Schocken Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, LLC.

eBook ISBN: 978-0-8052-4316-1

Hardcover ISBN: 978-0-8052-4278-2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Dauber, Jeremy Asher.

The worlds of Sholem Aleichem / Jeremy Dauber.

pagescm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8052-4278-2

1. Sholem Aleichem, 18591916. 2. Authors, Yiddish19th centuryBiography. 3. JewsUkraineBiography. I. Title.

PJ5129.R2Z576 2013 839.18309dc23 [B] 2013009267

www.schocken.com

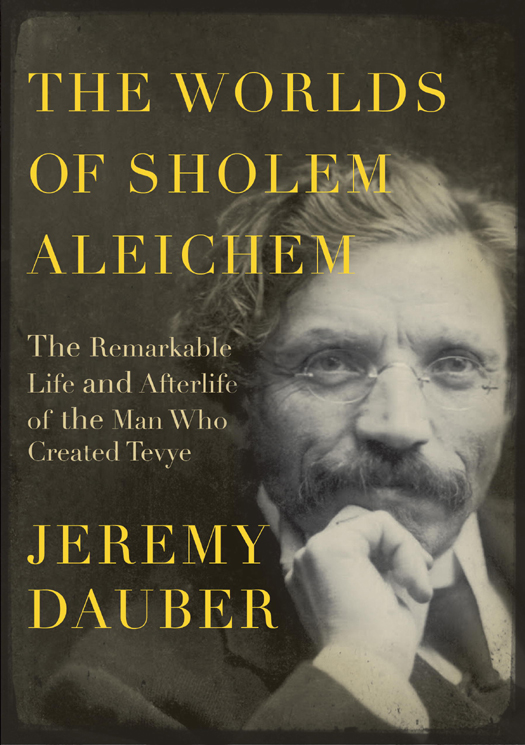

Jacket photograph of Sholem Aleichem, New York, 1907. Courtesy of Beit Sholem Aleichem Archives, Tel Aviv, Israel

Jacket design by Peter Mendelsund

First Edition

v3.1

For Eli

CONTENTS

OVERTURE

In Which We Set the Stage

H eres a Sholem Aleichem story, of a sort:

The mid-1990s. My college roommates wedding. He was a Methodist from rural Ohio, the first person I ever met with a rural free delivery address, marrying a wonderful woman from small-town Iowa. The wedding took place in Hartley, Iowathe town with a heart, the sign on the way into town attested. I was an usher. A guest, while being ceremoniously escorted to her pew, pointed at my kippah and proudly proclaimed she knew what it was; she had, after all, costumed Fiddler on the Roof.

And another:

The very late 1970s. My modern Orthodox day school. A first grade dramatic production. A half-dozen three-foot Tevyes in cotton-ball beards sing Do You Love Me? to a bevy of tiny Goldes. No other memory remains, for which I am eternally grateful. My parents claim it was cute.

I f youre an American, Jew or no, of a certain generational spanborn, say, between the time Sid Caesar first mugged for a television camera and the premiere of Seinfeldtheres no talking about Sholem Aleichem without talking about Fiddler on the Roof, the stage and screen adaptation of his greatest creation, Tevye the dairyman. Forget Sholem Aleichem: theres no talking about Yiddish, his language of art, without talking about Fiddler on the Roof. Theres no talking about Jews without talking about Fiddler.

And its not just Americans, either. Take a look at YouTube: as of early 2012, a clip titled Japanese Fiddler on the Roofwhich looks like a rehearsal in a high school gymhad racked up 571,764 views. You can also find significantly less popular but far more professional-looking Hindi and Hungarian versions. Closer to home, high school marching band performances and at least one sock puppet parody nestle side by side with a seemingly infinite number of shaky recordings of high school and community theater productions.

Tevye and his daughters belong to the world, apparently; and as arguably the most popular and powerful representatives of Jewish life to the world at large since the closing of the biblical canon (Superman, as a metaphor, doesnt count), they certainly merit a closer look in their original literary setting. But this book isnt Tevyes story, though by books end that story will be told. Its the remarkable saga of his remarkable creator, the story of the man behind the show: the man responsible, in his day and ours, for the most compelling picture of the world of our great-grandfathers, a society in dizzying, wrenching transition from the traditional life of centuries past to the modern age. Sholem Aleichem was no Tevye, though, no simple man with a few pithy quotes and some piquant conversations with his Creator; he was really Sholem Rabinovich, a first-class intellect and brilliant writer, who translated the momentous events of his day for an audience looking for nuance wrapped in simplicity.

And he was no detached observer; Sholem Rabinovich did it all. He was an orphan and a devoted family man, a struggling rabbi and a fantastically rich stockbroker; he wore the Gorky shirts of the left-wing agitators and left Russia to try his luck in Americawhen he wasnt attending Zionist congresses. He suffered through family tragedies, personal illness, commercial disasters, World War I, and a pogrom literally at his front door to write some of the most optimistic works of Yiddish literature ever pennedthough leavened with a strong dose of skepticism, sadly and honestly earned. His life is Jewish modernity writ smalljust as his great creation, Tevye, meets the changing world without ever leaving his daughters and his horse. In the biography of Sholem Aleichem, youll find a gripping narrative as exciting as any of his characters stories, complete with a grand romance, financial rise and ruin, a war or two, and at least one revolution.

But his life was his writing. A graphomaniac like few others, he wrote thousands and thousands of letters; his collected works run to twenty-eight volumesand include around half of his Yiddish output (to say nothing of his efforts in Hebrew and Russian). And it was in that writing that he did nothing less than create modern Jewish literature, modern Jewish humor, a modern Jewish homeland in literature. Before we get to that audacious claim, though, lets leave Sholem Aleichem, as he himself might have phrased it, and return to those first two anecdotes of mine, which, in their own small way, try to nod to Sholem Aleichems work.

Not because, or only because, both anecdotes revolve around Fiddler on the Roof. Both are monologues, a literary form he mastered and used to remarkable effect with characters great and small, Tevye first in their rank. At least one of the stories doesnt, strictly speaking, have an endinganother Sholem Aleichem characteristic, showcasing the fine line between humor and frustration that his stories sometimes, always intentionally, engendered. Their themesthe changing nature of Jewish identity in the modern world, particularly with respect to confronting non-Jewish life and culture, often filtered through the prism of romance, are all solidly in Sholem Aleichems wheelhouse, as every Fiddler viewer knows. And the tone: ironic, yes, but not immune to sentimentality; and ultimately optimistic, with a crowd-pleasing focus on lovers and children. Thats Sholem Aleichem, too.

And both stories blur the line between author and literary character: a line Sholem Rabinovichwho, under that cheery pen name of Sholem Aleichem, Mr. How Do You Do, was often buttonholed, petitioned, or even annoyed by his other literary creationsdownright obliterated. In a time less attuned to postmodern game playing, his audiences sometimes confused literary persona with actual person; the 150,000 to 250,000 people who turned out for his funeral in New York in 1916the largest public funeral in New York City then on recordwere there to bury Sholem Aleichem, not Rabinovich. They had good reason for being confused: the author himself, as well see, was often an active and willing participant in the obfuscation.

Those men, women, and children who mobbed the New York streets mourned the writer who had given them (and us) a gallery of indelible charactersTevye, of course, but also the dreaming Menakhem-Mendl, and the cheerful orphan Motl, and the citizens of the little town of Kasrilevke, who had already risen to the level of byword and archetype. You will make their acquaintance in these pages, if you dont know them already, along with a host of other characters who, once met, are impossible to forget. But they were also mourning a culture hero, a symbol: of the man who held it all together, who contained multitudes, who