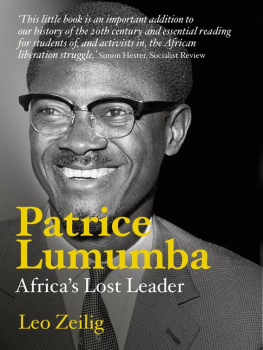

Leo Zeilig - Patrice Lumumba: Africas Lost Leader

Here you can read online Leo Zeilig - Patrice Lumumba: Africas Lost Leader full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2008, publisher: Haus Publishing, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Patrice Lumumba: Africas Lost Leader

- Author:

- Publisher:Haus Publishing

- Genre:

- Year:2008

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Patrice Lumumba: Africas Lost Leader: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Patrice Lumumba: Africas Lost Leader" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Patrice Lumumba: Africas Lost Leader — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Patrice Lumumba: Africas Lost Leader" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Lumumba is a martyr to the cause of African liberation and Leo Zelig has done him proud But, for socialists, this is not just heroic and tragic story, it is a vital lesson for struggles today and into the future Leo Zeligs little book is an important addition to our history of the twentieth century and essential reading for students of, and activists in, the African liberation struggle. Simon Hester, Socialist Review

In this well-researched book Leo Zeilig has done the valuable job of bringing to life Patrice Lumumba as a man, as well as showing the political context of Africa in the 1950s in the dying days of colonialism. This book is the key to understanding why Lumumba became such a potent myth. Victoria Brittain

An excellent introduction to the political and personal life of the most enigmatic African leader of the twentieth century. Ludo de Witte, author of The Assassination of Lumumba

Patrice Lumumba (192561) is perhaps the most famous leader of the African independence movement. After his murder in 1961 he became an icon of antiimperialist struggle. His picture was brandished on demonstrations in the 1960s across the world along with Che Guevara and Ho Chi Minh. His life and the independence that he sought for the Congo made him a pivotal figure of the 20th century. Lumumbas life marked out some of the key post-war fault lines in the second half of the 20th century; how the Cold War would be fought in Africa and the nature of the independence granted to huge swaths of the globe after 1945. For those fighting in liberation struggles, Lumumba became a figure of resistance to the imperial division of the world.

Later his wife would complain that his hair had been untidy and that there was no question she could attend the Independence Day ceremony with him in such a state. So Pauline Opango did not see her husband deliver the most important speech of his life. He had not been due to speak and there was some surprise in the audience when Joseph Kasongo, President of the Senate, announced the Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba. He moved towards the platform, flashbulbs firing around him. Perhaps Pauline listened to the speech on the radio at home.

We are proud of this struggle, of tears, of fire, and of blood, to the depths of our being, for it was a noble and just struggle, and indispensable to put an end to the humiliating slavery which was imposed upon us by force. This was our fate for eighty years of a colonial regime; our wounds are too fresh and too painful still for us to drive them from our memory. We have known harassing work, exacted in exchange for salaries which did not permit us to eat enough to drive away hunger, or to clothe ourselves, or to house ourselves decently, or to raise our children as creatures dear to us. We have seen our lands seized in the name of allegedly legal laws which in fact recognized only that might is right. The Republic of the Congo has been proclaimed, and our country is now in the hands of its own children.

The Congolese who were present detected no exaggeration in the speech. But the old colonial masters exploded in convulsions of rage at the sight of a Congolese man daring to speak this truth in front of the Belgian establishment. Belgium had occupied the Congo eight decades before in the name of civilisation . Colonial power in the early decades had been absolute and tyrannical.

Belgian interest in the Congo was stimulated by Henry Morton Stanley. In 1869, the owner of the New York Herald employed the 28-year-old reporter to search for the missionary and adventurer David Livingstone, who was presumed lost somewhere in the Congo. Over a period of 20 years, Stanley more than anyone helped to establish the Belgian empire in the Congo.

Perhaps the best way to understand Stanley is to see him simply as a speculator . His books describing his exploration of central Africa were accounts of the riches that could be found in the region, that were used to entice western states. Stanley systematically detailed the precious woods, ivory and minerals : It may be presumed that there are about 200,000 elephants in about 15,000 herds in the Congo basin, each carrying, let us say, on an average 50 lbs. weight of ivory in his head, which would represent, when collected and sold in Europe, 5,000,000.

The Congo River that Stanley originally sought to map was presented as the principle passage that could be used to access the resources he had painstakingly catalogued. Originally his efforts were directed towards the British, appealing to their seemingly insatiable appetite for African territory. But the British rejected his offers. Stanley then turned to Lopold II, King of the Belgians, who snapped up one of the last regions of the continent as yet unoccupied by other European powers. Stanley met Lopold for the first time in June 1878. By the end of the year he was employed on a contract worth up to 50,000 francs a year (250,000 in todays money).

Faithful to his new paymaster Stanley was charged with setting up trading stations, and dealing with local chiefs that would ensure Lopolds access to the wealth Stanley had promised. Under the guise of free trade Lopold gave favoured companies concessions to invest in the territory, keeping a majority share for himself. Money flowed almost immediately into Lopolds court.

Stanley persuaded hundreds of Congolese chiefs to hand over sovereignty by signing treaties in the name of Lopold. Adam Hochschild explains what these treaties really were: The very word treaty is a euphemism, for many chiefs had no idea what they were signing. Few had seen the written word before, and they were being asked to mark their Xs to documents in a foreign language and in legalese. The idea of a treaty of friendship between two clans or villages was familiar; the idea of signing over ones land to someone on the other side of the world was inconceivable. Did the chiefs of Ngombi and Mafela, for example, have any idea of what they agreed to on April 1, 1884? In return for one piece of cloth per month to each of the under-signed chiefs, besides presents of cloth in hand, they promised to freely of their own accord, for themselves, and their heirs and successors for ever give up to the

When Stanley returned to Lopolds court in 1884 he could boast of at least 500 treaties. He also announced that he had founded Vivi, the first capital of Congo and the town of Lopoldville (todays Kinshasa). These were great gifts indeed for the king.

Lopolds fascination with the Congo represented Belgiums position in the world. Belgium was a new state, having only achieved independence in 1830. Across Europe a relatively new class had emerged. The bourgeoisie symbolised the drive for profit and industrialisation, transforming European societies. But in Belgium this class of entrepreneurs and businessmen was less forthright than their European rivals. Ludo de Witte describes Belgium during the period: the structure of the Belgian bourgeoisie, which at the time the Congo was created by King Lopold II, was a very young, weak, fragmented class, with little confidence in itself and its projects. It was certainly imperialistic and was trying to organise itself with investments abroad. But the idea of conquering a colony for itself was something that seemed too ambitious for the small bourgeoisie of Belgium. It was only the actions of the Belgian King that ensured the Congo would come into existence and the only way the King could get the Belgian bourgeoisie involved in the colonial adventure, as it was known, was to give huge concessions to Belgian companies. So what you had was a very small group of very powerful Belgian businesses, who got huge concessions in the Congo, and made super-profits.

The 18845 Berlin Conference attempted to resolve quarrels between European powers scrambling for influence in Africa. The Conference officially recognised Lopold as the legal head of the euphemistically named International African Association of the Congo, soon renamed as the Congo Free State. The stated aims of the new Belgian colony were to abolish slavery and war would be waged against Arab slave traders for this purpose and promote free trade.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Patrice Lumumba: Africas Lost Leader»

Look at similar books to Patrice Lumumba: Africas Lost Leader. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Patrice Lumumba: Africas Lost Leader and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.