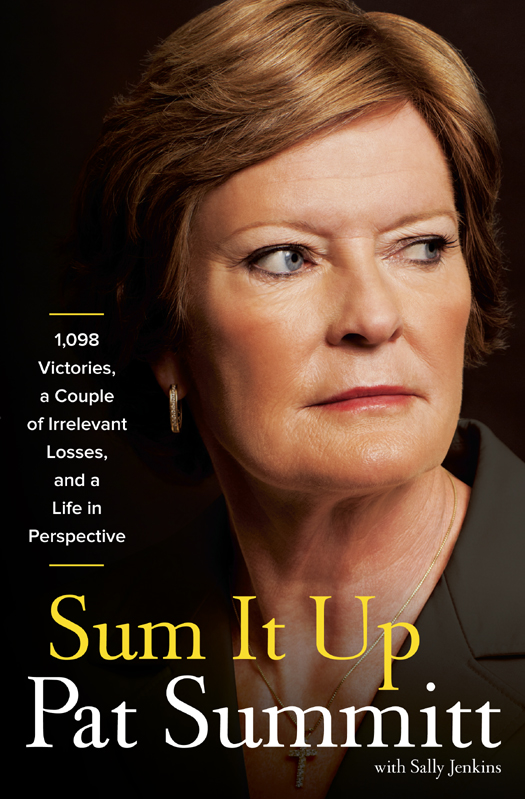

Copyright 2013 by Pat Head Summitt

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Crown Archetype,

an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group,

a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

Crown Archetype with colophon is a trademark of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Summitt, Pat Head, 1952

Sum it up: a thousand and ninety-eight victories, a couple of irrelevant losses, and a life in perspective / Pat Summitt with Sally Jenkins. First edition.

pages cm

1. Summitt, Pat Head, 1952 Mental health. 2. Alzheimers diseasePatientsBiography. 3. Basketball coachesUnited StatesBiography. 4. Tennessee Volunteers (Basketball team)History.

I. Jenkins, Sally. II. Title.

RC523.3.S86 2013

362.1968310092dc23

[B] 2012050333

eISBN: 978-0-385-34688-7

Jacket design by Michael Nagin

Jacket photography by Bradley Spitzer

v3.1

Dedicated to my families, original and extended: to my son, my mother, my siblings and their families; to my players and their parents and grandparents who made me part of their lives; to the many coaches and coaching mentors Ive had the honor to work with who are as close as family; to the many friends who might as well be sisters and brothers; and finally to the family of people who combat Alzheimers disease

Contents

I know theres something else Im supposed to be doing.

Theres something God wants me to do.

Like what?

Im not sure.

You dont think winning eight national championships and raising a son is enough? You think theres something more youre supposed to be doing?

I know theres something else. I feel it.

February 23, 2011, on a road trip to Oxford, Mississippi, three months before diagnosis

1

Footprints in the Sand

I remember a Tennessee field with hay as far as I could see and a tall man standing in it, staring at me with pale blue eyes. Eyes that you wanted to look away from. Daunting eyes. My father had eyes that gave me the feeling he could order up any kind of weather he wanted, just by looking at the sky. If the tobacco crop needed rain, hed glare upward, until I swore it got cloudy. I gestured at the hay field and said, Daddy, how long do I have to stay out here? He said, Youll be finished when its done. And its not done till its done right.

I remember a leaning gray barn with an iron basketball rim mounted in the hayloft. At night after the choresafter it was done, and done rightmy three older brothers and I climbed to the loft for ball games in which they offered no quarter. Just elbows and fists, and the advice Dont you cry, girl. I better not see you cry. I remember learning to hit backhard enough to send them through the gallery door into a ten-foot drop to the bales below.

I remember the supper table crammed with bodies, children with clattering forks fighting over the last piece of chicken, and my mild, selfless mother, filling the glasses and plates with a close-lipped smile and a voice soft as a housedress, and then I remember watching her muscle a two-ton truck into gear and roar off to pick up farm supplies.

I remember the searing smell of the ammonia that my college coach waved under my nose, and heavy polyester uniforms with crooked numerals, and the dark hotbox auxiliary gyms with no air-conditioning where they stuck women, one in particular leaking light from holes in the roof, through which birds flapped and splattered their droppings on the floor.

I remember being young and wild with energy, conducting searches for amber liquid refreshments, pulling into joints that sold twenty-cent beer.

Whats your brand?

Cold.

I remember standing on a medal podium in the 1976 Montreal Olympics, imbued with a sense that if you won enough basketball games, there was no such thing as poor, or backward, or country, or female, or inferior.

I remember every playerevery single onewho wore the Tennessee orange, a shade that our rivals hate, a bold, aggravating color that you can usually find on a roadside crew, or in a correctional institution, as my friend Wendy Larry jokes. But to us the color is a flag of pride, because it identifies us as Lady Vols and therefore as women of an unmistakable type. Fighters. I remember how many of them fought for a better life for themselves. I just met them halfway.

I remember the faces on the young women who ran suicide drills, flame-lunged and set-jawed, while I drove them on with a stare that burned up the ground between them and me. I remember the sound of my own voice, shouting. Holdsclaw, sprint through the line! Urgent, determined. Snow, youre stronger than you think! You dont ever let other people tell you who you are! Exasperated, mocking, baiting. Holly Warlick, just get out of the drill. Just get out. Put someone in who can throw a pass.

When you see Pats heartbeat in her neck, youre in trouble. Big trouble. You dont want to look in her eyes, so you try to look someplace else, and then you find her neckand you see her heartbeat in her neck. Also, you see her teeth gritting. Thats not real cool either.

H OLLY W ARLICK

I remember being able to almost read their thoughts. That lady is crazy; why is she torturing us? (They embellish.) I cant ever satisfy her; what does she want from me? (Only everything.) Man, Im getting a bus ticket and going back to New York. Or Indiana. Or Oregon. Or coal country Kentucky.

Yeah, I would recommend playing for Pat Summitt, Abby Conklin liked to say, if a year of counseling comes with it.

Bless their hearts.

I remember chewing the inside of my lower lip over losses, until I had a permanent entrenched scar. I remember asking my friends and family two questions after every NCAA championship game.

Do you think I was too hard on them?

What did Daddy say?

I remember being so possessed by the job that I coached in my sleep. Id toss and kick until I woke myself up hollering, Git down the floor!

I remember standing on the sideline and stamping my high heels on the hardwood so furiously it sounded like gunshots, and whacking my hands on the scorers table until I flattened the gold championship rings on my fingers.

I remember jabbing a finger into an officials face and backing him from midcourt to the baseline.

I remember the sound of certainty in my own voice, lifted over the roar of twenty thousand people and two rivalrous marching bands in a sold-out arena at the NCAA Final Four, as I told our players that though they trailed by eleven points with seven minutes to go, the game was ours. Were not leaving here without a championship! I shouted hoarsely. So yall just go on out there and get it!

I remember how intensely in the moment I felt in big games. I remember the second-by-second adjustments, the dialing up of players emotions in the huddles, operating on pure feel, calling plays less by rational process than by some buried sense of rhythm, that now is the time for a change of pace. I remember the speed of the decision makingwho needs the ball, who needs to be in the gameand how I loved that. Loved it.

I remember the laughter that was always equal to the shouting, great geysers of it that went with victory champagne. Peals of stress-relieving hilarity behind closed doors with assistant coaches who have been more close friends than colleagues, Mickie DeMoss, Holly Warlick, Dean Lockwood, Nikki Caldwell. I remember Mickie, the queen of one-liners, razzing Dean about a date he wouldnt introduce us to. You know, Dean, she said, you can always get her teeth fixed, and all of us whooped until we banged our silverware on the table.