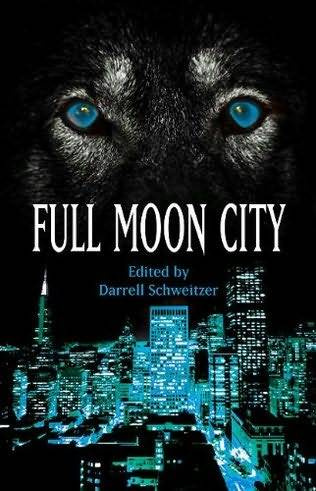

Darrell Schweitzer, Martin Harry Greenberg, Lisa Tuttle, Gene Wolfe, Carrie Vaughn, Esther M. Friesner, Tanith Lee, Holly Phillips, Mike Resnick, P. D. Cacek, Holly Black, Ian Watson, Ron Goulart, Darrell Schweitzer, Chelsea Quinn Yarbro, Gregory Frost, Peter S. Beagle

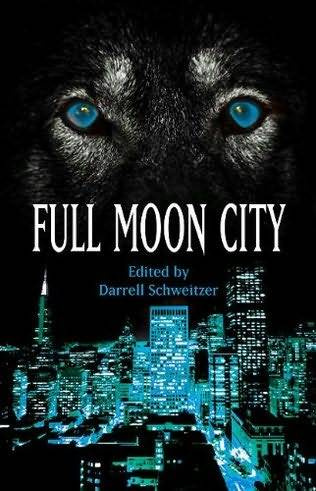

Full MoonCity

2010

Compilation copyright 2010 by Tekno Books and Darrell Schweitzer

Introduction copyright 2010 by Darrell Schweitzer

The Truth About Werewolves copyright 2010 by Lisa Tuttle

Innocent copyright 2010 by Gene Wolfe

Kitty Learns the Ropes copyright 2010 by Carrie Vaughn, LLC

No Children, No Pets copyright 2010 by Esther M. Friesner

Sea Warg copyright 2010 by Tanith Lee

Country Mothers Sons copyright 2010 by Holly Phillips

A Most Unusual Greyhound copyright 2010 by Mike Resnick

The Bitch copyright 2010 by P. D. Cacek

The Aarne-Thompson Classification Revue copyright 2010 by Holly Black

Weredog of Bucharest copyright 2010 by Ian Watson

I Was a Middle-Age Werewolf copyright 2010 by Ron Goulart

Kvetchulas Daughter copyright 2010 by Darrell Schweitzer

And Bobs Your Uncle copyright 2010 by Chelsea Quinn Yarbro

The Bank Job copyright 2010 by Gregory Frost

La Lune T Attend copyright 2010 by Peter S. Beagle

Children of the Night

Mostly, we fear them.

When Bela Lugosis vampire Count praised wolves in the 1931 film, this was used to emphasize Draculas inhuman, otherworldly nature. It produced some of the most memorable lines ever uttered on the silver screen:

The children of the night. What music they make.

I doubt it was ordinary wolves he had in mind, either. The uncanny must surely be sensitive to the uncanny, even though, one imagines, vampires might well envy werewolves. After all, vampires are dead, forced to steal vitality to maintain a shadow existence, whereas werewolves are very much alive, maybe even too vital.

Dracula had lycanthropic powers. He could transform himself into an enormous wolf when need be.

The wolf remains a symbol of power and fear. Very likely this is programmed into our genes from the days of our barely-human ancestors, who once had to take on the fanged and clawed world with no more than a club, a pointed stick, or, at best, a piece of sharpened flint. One wolf, when the odds are more or less even like that, can be formidable. An organized pack can bring down a moose, or a man, with ease. It is hard to believe that in times of famine, in the depths of winter, they didnt occasionally do so. Wolves remain, in folklore, stories, and fairy tales, one of the terrors that come in the night, despite the efforts of naturalists such as Farley Mowat (Never Cry Wolf) to convince us that wolves have gotten entirely too much bad press.

The more traditional image of the wolf emerges clearly in Daniel P. Mannixs The Wolves of Paris (1978), a nonfiction account of how, in the midst of the Hundred Years War (fourteenth century), great hordes of wolves roamed the devastated French countryside, devouring man and beast alike, until they actually besieged the walled city of Paris. Understandably, the enormous creature at the head of this wolf pack was assumed to be a werewolf.

Belief in shape-shifters is as old as mankind. (Not just werewolves, either; in some parts of the world you can find wereleopards, werehyenas, and so on.) You can well imagine the caveman, huddled around his fire with the rest of his tiny band, listening to the cries of animals in the night-their music-and knowing that, to him, the night landscape was forbidden territory. To wander far from the fire meant death. Hed had that hammered into his head since childhood. For the survival of the tribe, it was crucial that he teach his children the same thing. What could be more impressive and terrifying than a human being who transformed into the very creature everyone else feared and ventured out into that forbidden night-realm?

Of course, not all cultures see werewolves as the enemy. Some Native Americans viewed them as benevolent. This may have been because Native Americans were better outdoorsmen than medieval French peasants and had less to fear, although certainly American werewolves still must have been seen as creatures of awe and mystery.

The werewolf has been in literature for a long time. The best-known example from Antiquity is very likely the werewolf story told over the dinner table in the Satyricon of Petronius, written in the time of Nero. Here we see a very familiar motif: A man turns into a wolf and commits his depredations. His guilt is proven afterward when, back in human form, he bears marks of an injury inflicted on the wolf.

Gene Wolfe, in his meticulously researched novel Soldier of the Mist (1986), tells us that in Greece in the fifth century B.C., it was common knowledge that Scythians were werewolves.

I dont doubt it.

There are werewolf stories from the Middle Ages, too. The Lay of the Werewolf by Marie de France (twelfth century) presents a sympathetic werewolf who confides his secret to his wife one night, whereupon she hides his clothes so that he cannot return to human form and she can run off with her lover. The werewolf acts the role of a tame beast, wins the favor of the king, and eventually regains his humanity. The wife is punished, but the werewolf is not, even after everybody learns what he is.

Nevertheless, werewolves are feared more often than not, if only for their propensity for eating people. (Whether wolves have ever eaten anyone is a subject disputed among naturalists. That werewolves do so is not.) If anything, the werewolf is an embodiment of uncontrolled rage and lust. We define our humanity precisely by our ability to control our bestial tendencies. The werewolf, therefore, may be seen as ourselves, with every trace of civilization and social inhibition stripped away.

While there is no single werewolf story or novel that defines the whole genre in the way that Bram Stokers Dracula defines the vampire, two books do stand out and represent different strands in the development of the literary werewolf.

The Werewolf of Paris by Guy Endore (1933) is the classic novel of the supernatural werewolf, set in nineteenth-century France. The protagonist, Bertrand Caillet, is the offspring of a woman raped by a priest, who is himself of an accursed line. Bertrand has all the classic werewolf characteristics, including eyebrows that meet and hairy palms. He experiences blackouts, excessive urination (possibly to mark territory; this detail is also mentioned in Petronius), and hunts animals first, then people. The climax of the book finds him in Paris during the turmoil of the Commune (1870) and its bloody suppression, against which background-as is very much the authors point-one small werewolf seems quite insignificant amid an orgy of human cruelty.

Jack Williamsons Darker Than You Think (magazine version, 1940; expanded as a book, 1948) presents the scientific werewolf, based on the notion that a rival, shape-shifting race, Homo lycanthropus, lives alongside mankind and is poised to regain the world mastery it once enjoyed in prehistoric times. Other more recent books, notably Whitley Striebers The Wolfen (1979), expand on Williamsons thesis.

The werewolf has also been equated with that very contemporary horror icon, the serial killer, with whom, indeed, he has much in common. (What was Ted Bundy but a werewolf without the excess hair?) Yet Stefan Dziemianowicz makes an excellent case in his entry on werewolves in S. T. Joshis Icons of Horror and the Supernatural

Next page