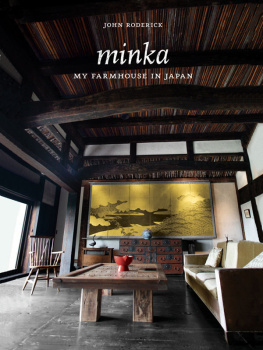

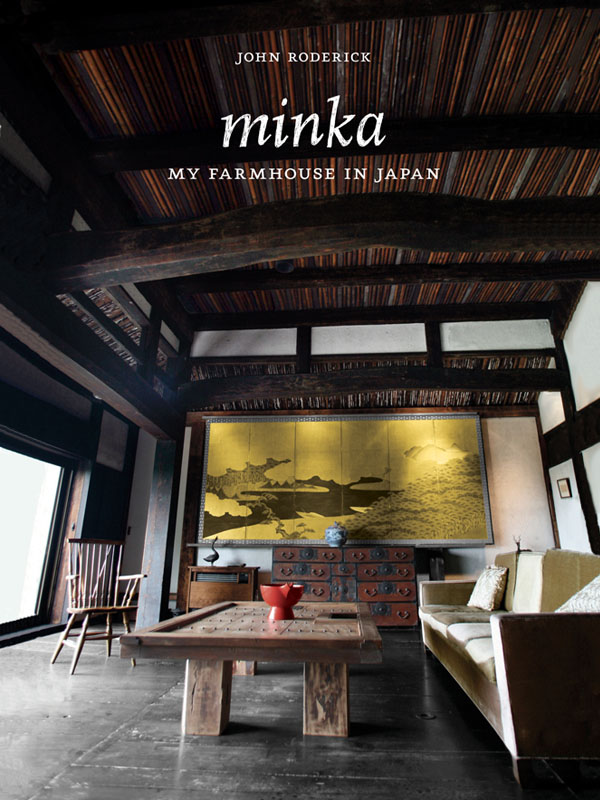

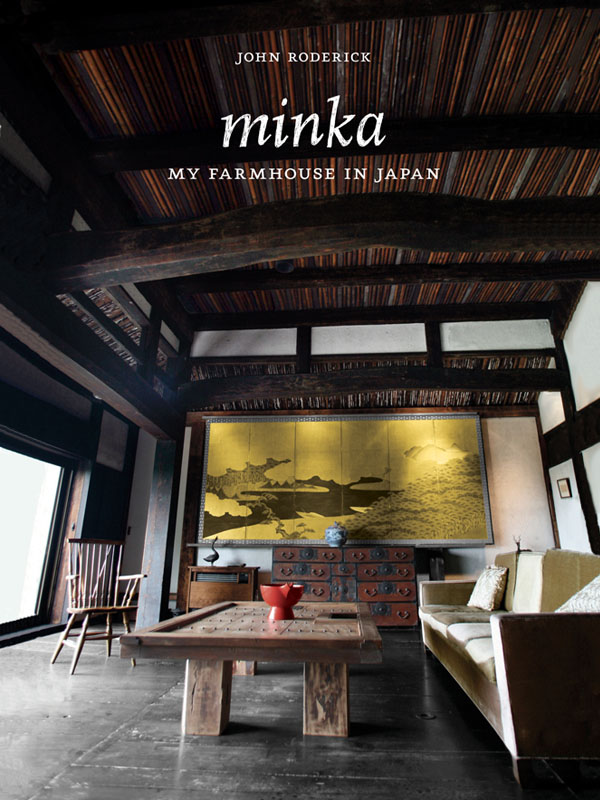

Minka

Minka

My Farmhouse in Japan

John Roderick

PRINCETON ARCHITECTURAL PRESS

NEW YORK

Published by

Princeton Architectural Press

37 East Seventh Street

New York, New York 10003

For a free catalog of books, call 1.800.722.6657.

Visit our website at www.papress.com.

2008 John Roderick

All rights reserved

Printed and bound in China

11 10 09 08 4 3 2 1 First edition

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission from the publisher, except in the context of reviews.

Every reasonable attempt has been made to identify owners of copyright. Errors or omissions will be corrected in subsequent editions.

Image credits

AP Photo: 250

Shizuo Kamabayashi/AP: 249b, 251t

Yoshihiro Takishita via AP: 99, 107

All other images courtesy of Yoshihiro Takishita

Editor: Dorothy Ball

Designer print edition: Arnoud Verhaeghe

Special thanks to: Nettie Aljian, Sara Bader, Nicola Bednarek, Janet Behning, Becca Casbon, Penny (Yuen Pik) Chu, Russell Fernandez, Pete Fitzpatrick,Wendy Fuller, Jan Haux, Clare Jacobson, John King, Nancy Eklund Later, Linda Lee, Laurie Manfra, Katharine Myers, Lauren Nelson Packard, Jennifer Thompson, Paul Wagner, Joseph Weston, and Deb Wood of Princeton Architectural Press Kevin C. Lippert, publisher

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Roderick, John.

Minka : my farmhouse in Japan / John Roderick. 1st ed.

p. cm.

ISBN-13: 978-1-56898-731-6 (alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 1-56898-731-5 (alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-56898-962-4 (digital)

1. Architecture, DomesticJapanIse-shi. 2. FarmhousesJapanIse-shi. 3. Vernacular architectureJapanIse-shi. 4. Roderick, JohnHomes and hauntsJapanKamakura-shi. I. Title.

NA7451.R63 2007

728.370952dc22 2007015697

For Yochan and the Takishita family,

with all my love.

We shape our buildings, and afterwards our buildings shape us.

WINSTON CHURCHILL

Prologue

When the hurly-burly of todays world overwhelms me with its news of the never-ending war between good and evil, love and hate, I hobnob with the rustic ghosts of centuries past in my restored old farmhouse on a hill, overlooking Kamakura, the ancient capital of Japan.

Its steep snow roof, massive posts and beams, wide wooden floors, and split-bamboo ceilings take me back 273 years to the tiny hamlet of rice farmers in the mountains where it was born, 350 miles from Kamakura.

The event on that distant day was a jubilant one because it was built for the village chief, Tsunetoshi Nomura, who doubled as its nature-worshipping Shinto priest. The place: Ise, in Fukui prefecture, 400 miles west of Tokyo. Its scattering of farmers all lived in such big farmhouses, called minkas , now a sadly disappearing type of building more than 2,000 years old.

I became the owner of this venerable pile forty-two years ago thanks to my surrogate Japanese family, the Takishitas (a name meaning under the waterfall) of Gifu prefecture. They took me, an American journalist and recent wartime enemy, under their wing in 1963, five years after I arrived in Tokyo to join the Associated Press staff there.

Actually, the minka was a gift from its owner, Tsunemori Nomura, the affable descendant of that long-ago ancestor for whom it was built. Parting with it was, for him, an almost unbearable sorrow. His ancestors, officers of a brave but doomed military clan called the Heike, had hidden, lived, ministered, and died in Ise since they had found refuge there following their twelfth-century defeat by Yoritomo, the first of Japans long line of military rulers, called shogun .

What followed was a labor of love. The Takishitas, joined by friends and family, dismantled, moved, and rebuilt the immense old house in Kamakura, where I lived. After defeating the Heike, Yoritomo made Kamakurahis military headquartersthe capital of a united Japan. The ghosts of the Ise Nomuras must have laughed bitterly to see their old home come to life again in the seat of their ancient enemy. Yoshihiro, the youngest Takishita son, a recent university graduate, supervised the entire project. It took forty days.

In my forty years as a foreign correspondent, I covered the Chinese civil war, the strife surrounding the creation of Israel, and the French and American failures in Vietnam.

I spent seven months with the Chinese communist leader, Mao Tse-tung, in his 1940s cave capital of Yanan. And over the next thirty years, I chronicled the slow and sinister change in his personality from one of compassion for his fellow Chinese to blind hatred toward anyone blocking his dreams of personal power and conquest.

Turning from agrarian idealist to dictatorial tyrant, he publicly proclaimed that love was a bourgeois weakness, hate mans most powerful emotion. Yet I cannot believe him; I am still convinced that in the end the meek will inherit the earth.

Searching for an example of the power of love, I have drawn on my own experience, the Takishita familys gift of love and friendship whose living symbol is the old minka in which I still live.

It is a small example but it is significant because it happened in Japan, an implacable enemy that Iand so many Americansonce hated, intensely, blindly, and totally.

Often, in the eloquent silence of my high-ceilinged living room, I think I hear the voices of the Nomuras and their neighbors, chattering about the weather, the harvest, fishing, the hunt, the phases of the moon, and the religious mysteries of the deep forests.

It is then that the lovely old minka speaks to me of a time when nature and the rural sense of community sharing informed everyday life. Forty years after the Takishitas presented it to me, it is my private shelter from the global storms that rage all around us.

It represents, to me, the triumph of love over hate.

It is, at last, a house of my own.

Book One

The beautiful is that which cannot be changed except for the worse; a beautiful building is one to which nothing can be added and from which nothing can be taken away.

LEON BATTISTA ALBERTI

A Breakfast to Remember

On the afternoon of Sunday December 7, 1941, I began to hate Japan and the Japanese, a nation and a race I hardly knew.

I was twenty-six then, the only editor on duty in the Portland, Maine, bureau of the Associated Press. It seemed like a quiet, eventless Sunday until the bells on our teletype machines began clanging, waking me from the daydream into which I had fallen.

The urgent message read:

JAPS BOMB PEARL HARBOR

The details came clattering over the teletypes: Carrier-based Imperial Japanese Navy bombers armed with torpedoes had, without warning, destroyed much of the U.S. fleet moored at Pearl Harbor on the Hawaiian island of Oahu. Eight battleships were sunk or severely damaged, 188 aircraft destroyed, 2,280 military men killed, and 1,109 wounded. Sixty-eight civilians also died.

The next day President Franklin D. Roosevelt described December 7 as a date which will live in infamy and congress declared war on Japan.

In the twenty-first century, the enemy is less visible, harder to pin down. He operates from secret headquarters and strikes at many targets hard to identify and defend. But there was no question about the enemy in 1941. It was Imperial Japan. A mixture of fact, fiction, and propaganda over the war years persuaded me, and millions of other Americans, that Japan was evil and the Japanese were monsters, buck-toothed, near-sighted, slow-witted, and cruel.

Next page