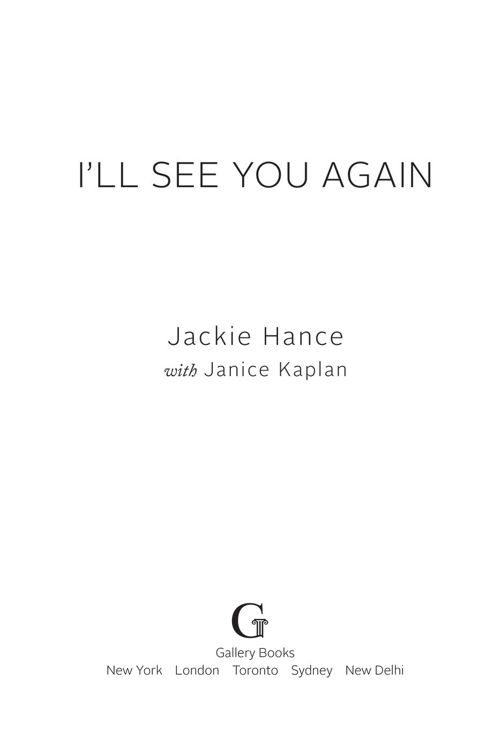

Contents

To the community

of loving friends and family

who have helped us find light

in the darkness

PROLOGUE

July 26, 2009

W arren drives frantically toward the police barracks in Tarrytown, New York, tightly clutching the wheel of his Acura. His three little fair-haired daughters should be heading home right now in a two-tone red Windstar, driven by his sister, Diane, but something has happened. Hes gone to the spot on the road where he told his sister to wait, but saw no sign of any of them. Not Diane or her two children. Not his three girls.

Cars dont disappear. Children dont vanish from the earth.

The police barracks looms ahead. Warren rushes in, and his father, who has come with him, follows behind. Warren starts to blurt out his story, but the troopers are already aware of the situation.

Somebody else gave us the information, one tells him. Maybe your wife.

The police claim they have done a twenty-five-mile-radius search, and theres no sign of the missing car. Later, Warren will wonder how they could have missed it.

Children dont vanish from the earth.

After his last call with her, when she sounded so ill, Diane stopped answering her cell phone. Now Warren suggests that the police try to track it. Cell phones have GPS, and pinging a signal always works in the movies. If they locate the phone, maybe they can find her. In the background, Warren hears one of the officers take a 911 call from his friend Brad, who has also called to report the situation. Missing car. Missing children. Huge worry.

The police, less concerned, gently urge Warren to leave.

Theres a diner about a mile down the street, one of the cops says. If your sister wasnt feeling well on the road, maybe thats where she went, to get something to eat.

Warren and his father drive to the diner, but the Windstar isnt in the parking lot. As they drive around aimlessly for a few minutes, a sense of futility engulfs them, and Warren turns back to the police station. This time, the moment Warren pulls up, a trooper rushes out and opens the door of a police vehicle.

Get in the car, he calls out to Warren. Ive got to take you to the hospital.

Warren feels the blood drain from his head. This is bad, he says to his father.

They get to the hospital, and Warren rushes in, yelling for his girlshis daughters, his life. Nobody has told him anything.

Where are my children? he asks.

A trooper who is waiting there takes him to a side room. He tells Warren the news.

Warren slams his fist, making a hole in the wall. Then another. He would punch a hole in the universe if he could, stop time, make it turn back. The trooper begins to sob, devastated. He shows Warren a picture of his own baby and Warren claps him on the back as the trooper cries in sympathy and fear and frustration.

A strange composure descends on Warren. He wants to talk to somebody about organ donation, to see how he can help even as his own life is disintegrating. But there is confusion everywhere, and the troopers are gone.

He asks for a room with a phone where he can be alone.

His first call is home.

Warrens fathers version of a BlackBerry is a scrap of paper in his wallet with phone numbers of all the aunts and uncles and cousins. He hands it to Warren, who calls every one. He wants to be the one to tell them.

An hour or so later, three of his close friends come into the hospital. Brad and Rob flank Warren and lead him outside, where their friend Doug is in a car to whisk him home. As his father stays behind to be with Dianes husband, Warrens community of friends is already coming together to protect him.

A hundred yards away, reporters are beginning to arrive at the hospital with microphones and cameras. Its a big story. Someone must have something to say. But nobody notices the grieving father as he leaves the hospital.

Part One

2009

One

S ummers are supposed to be relaxing, so how did this one become so hectic? I thought as I started packing up Emma, Alyson, and Katie for a weekend trip with their aunt Diane, uncle Danny, and two little cousins.

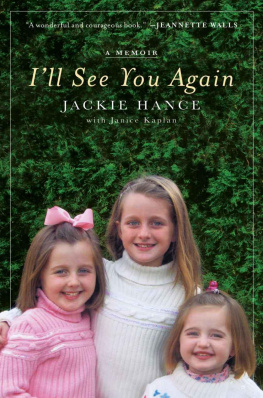

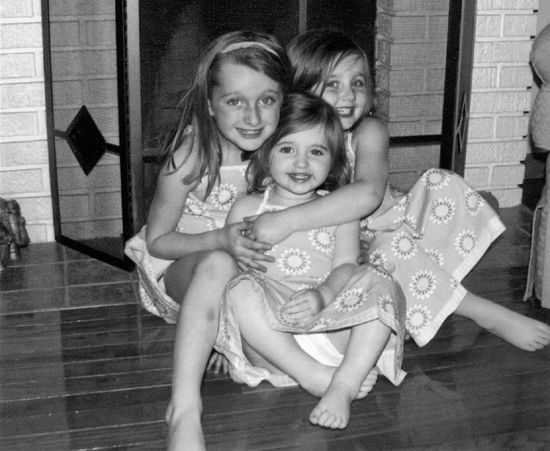

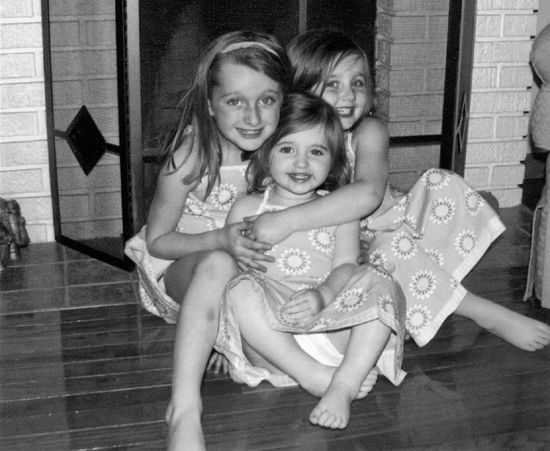

The girls had more activities than ever, and I seemed to spend all day driving them one place or another. The camping trip this weekend would be a peaceful break for everyone, even though I didnt like the thought of Emma, Alyson, and Katieeight, seven, and five years oldgoing away without me. We were almost never apart. But they had been looking forward to joining their aunt and uncle at the upstate campgroundand I would have two whole days with no car pools to drive.

I pulled the girls duffel bags out of the closet and lined them up in the bedroom.

The pink duffel said Emma in blue lettering. The blue one had Alyson inscribed in pink. And the smallest purple bag had a pink Katie on it. Very cute. Just like my girls: each bag was distinctive, and the three together created a lovely harmony.

I took shorts, T-shirts, and bathing suits from the dresser drawers and piled them on the beds so that the girls could make their own selections. Though they were young, each of my daughters already had a sense of style and definite ideas about what to wear, so it wouldnt do just to make the decisions for them.

A few minutes later, Emma, Alyson, and Katie crowded into the room, chatting and giggling, and started to pack. The sounds of three little girls make a special kind of music, and the walls of our house always resounded with the girls laughter and the sweet clamor of happy voices. I wasnt looking forward to the quiet that would descend when they left.

We need bathing suits! said Emma. Dont forget bathing suits, Mommy!

Theyre on the bed, I said, pointing. Emma and Alyson were already good swimmers, and Katie had been learning this summer at camp. I myself rarely stepped into an ocean or a pool, but I was glad my daughters had more courage. I didnt have to worry about them in the water.

Youre getting to be such a good swimmer, I said to Katie. Youre going to have so much fun at the lake.

Would you swim with us if you came? Katie asked.

I dont like lakes, I admitted. Theyre all icky on the bottom.

Oh, Mommy, youre silly! said Alyson.

Well wear water shoes so the lake wont feel icky, said Emma, being practical.

Alyson turned her bright smile at me. Do you think the crab would have gotten you if you had water shoes?

I laughed. The Mommy-bitten-by-a-crab story was part of family lore. When I was exactly Alysons age, I had gone into the ocean one day near my childhood home in New Jersey. I felt a sharp ping on my toes and ran screaming from the water. When I got to the beach, I saw that the nails on both of my big toes were gone.

I concluded that a crab had bitten them off.

And they never grew back right.

Hence, my fear of water.

Now Emma looked at me skeptically as I retold the story. She was old enoughand smart enoughto ask a lot of questions.

How could one crab bite off both your toenails? she asked.

I dont know, but it happened, I said.

Mommy, there are no crabs in lakes, so youd be okay, Alyson promised.

We got busy filling duffels with all the clothes three little girls could possibly wear in two days. I looked around the room to make sure they hadnt forgotten anything important.