Table of Contents

ALSO BY STEFAN KLEIN

The Science of Happiness

The Secret Pulse of Time

For Irene

Portrait of Leonardo

INTRODUCTION:

The Mystery of the Ten Thousand Pages

THE YEAR WAS 1520, A young nobleman and his entourage were leaving the castle of the French king in Amboise. They crossed over the Loire, rode along the river, then headed into forests in the south. The nobleman, Francesco Melzi, had with him a piece of luggage that was not especially large, but so heavy that two men were needed to move it. Even so, Melzi did not let this chest out of his sight for a single moment during the week it took him to travel back to Italy. Once in Milan, the group headed east. After an additional day of travel, the travelers reached a plateau over the town of Vapio dAdda at the foot of the Alps, where the young man dismounted at his familys majestic country estate. The chest was brought to an upper floor, and Melzi watched over it there for the next fifty years.

He was often visited by envoys from the ruling houses of Italy, who had heard about the unique treasure Melzi had in his possession. He sent them away. Had he served his master faithfully for more than a decade only to sell his work to the highest bidder? Leonardo da Vinci had died on May 2, 1519, at the court of Franois I of France, but Melzis affection for him was stronger than ever. He was like the best of fathers to me, he had written from Amboise to Leonardos half brothers, and vowed that as long as I have breath in my body I will grieve for him.... Each of us must mourn the death of this man, because nature will never have the power to create another like him.

Melzi began to sift through his inheritance. Leonardo had bequeathed him about ten thousand pageshis entire vast oeuvre apart from the paintings. The young noblemans fortune afforded him the leisure to dedicate himself wholly to his mentors bequest, though he soon realized that one lifetime would not be enough to put this estate in order. He hired two secretaries and tried to dictate at least some of Leonardos ideas to them. He also painted the way the master had taught him. For guests who wanted to look rather than buy, he was happy to grant access to the inner sanctum of the villathe room in which Leonardo had once lived and to which his creations had now returned.

Huge sheets of paper were piled up there, along with notepads smaller than the palm of the hand, notebooks bound in leather by Leonardo himself, and an immense quantity of loose papers of all sizes. These were far more than mere jottings by an extraordinary artist; they encapsulated his entire lifethe unparalleled ascent of an illegitimate day laborers son to a man courted by the rulers of Italy, who in his final years chose the friendship of the king of France, the path of a boy who had no higher education but would go down in history as the most famous painter of all time, and at the same time as a trail-blazer in science. We cannot tell whether any visitor studied Melzis collection the way it deserved to be studied; reading Leonardos mirror writing is no easy task. But anyone who went to the effort of reading the lines from right to left, and the notebooks from back to front, could learn about Leonardos military expeditions with the dreaded Cesare Borgia, captain general of the papal army, his adventurous escapes, and his trouble with the pope. Leonardo da Vinci had experienced successes and failures, fear for his livelihood, and boundless luxury; he had been both despised and worshiped.

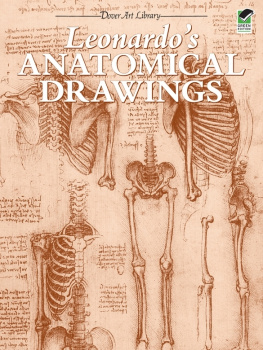

His sketches offered a vision of a distant future in which people would understand the forces of nature and work with machines. There were flying machines, formidable catapults, automatons in human form, and tunneled-through mountains. Turning a single page would transport visitors to this collection to a very different, though no less fantastic, world. Leonardo used chalk and pen to draw the inside of a human heart and a fetus growing in a womb. Other drawings showed aerial views of Italian landscapes and citiesthe way we might see them from an airplane today.

Melzis collection afforded unique insights into the workings of Leonardos mind. Ideas and dreams were laid out on paper; prophecies and a philosophy of life, theories about the origin of the world, plans for books; Leonardo had even written out shopping lists. He seems to have carried his notebooks fastened to his belt. In any case, he must have always had them with him to make sure that no idea would go unrecorded. It is rare indeed for an individual to keep such a detailed account of the dictates of his mind. Whoever understood Leonardos notes could follow his train of thought on his flights of fancy and was privy to his doubts and contradictions. The notes document the interior monologue of a lonely man, his fear of not living up to his own expectations, and his awareness of the price of fame: When the fig-tree stood without fruit no one looked at it. Wishing by producing this fruit to be praised by men, it was bent and broken by them. The chest Melzi had brought from France offered nothing less than a glimpse inside Leonardos brain.

One of the 10,000 pages: Reflections on the flight of birds

But Melzis prized possession is no longer intact. When Leonardos star pupil died of old age in 1570, his son Orazio proved indifferent to his fathers passion. He let the plunderers have at the collection. The familys private tutor sent thirteen stolen volumes to the grand duke of Tuscany. A huge bundle went to a sculptor named Pompeo Leoni, who in turn tried to bring order to the chaos by attacking Leonardos work with scissors and paste. If Leoni failed to see a connection between individual sketches on a given page, he simply cut them apart. He pasted the fragments onto sheets of paper, then bound and sold them. Leonardos tattered and torn legacy began to sprinkle across the libraries of Europe like confetti. A large part of the legacy is gone. About half of Melzis roughly ten thousand pages went missing. Studying the rest affords ample opportunity to admire the masters spectacular drawings, but the connections have been severed, and the spirit of Leonardo is no longer evident.

Even the plunderers did not diminish Leonardos posthumous fame; if anything, the gaps in Leonardos story created openings for myths. There are countless artists whose works have been preserved perfectly and are accessible to all, yet their names live on for no more than a few specialists. Leonardo, by contrast, whose works on public display number fewer than two dozen, continues to fascinate millions, half a millennium after his death.

The public is drawn to his works of art, of course, but even more to the man who created them. How could one individual fuse within himself what appeared to be knowledge of the entire worldand translate this knowledge into an unparalleled oeuvre? How was he able to create epoch-making paintingsand at the same time immerse himself in designing flying machines, robots, and all kinds of other devices and in contemplating a broad range of scientific questions? It seems miraculous that any one person could make his mark in so many areas in the course of a lifetime.