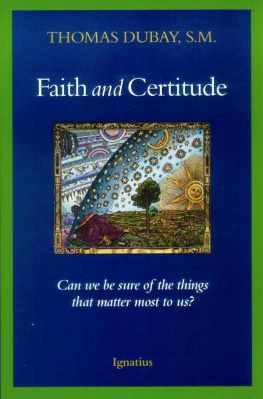

Introduction: Certitude

and Its Discontents

by Christopher Hitchens

Y ou sometimes hear people saying to their antagonists in debates on this or that topic: I envy you your certainty. One presumes that the origins of this expression must be ironic or even merely sarcastic, but there are also, rather touchingly, those who employ it literally and as a compliment. There are also those who, faced with doubt in its lack-of-faith form, will try to turn the tables by saying that unbelief is itself a form of fundamentalism. (This has lately become a favorite cheap debating trick of the religious Right.) By definition, of course, non-belief cannot be classified as a faithand its interesting to speculate about the degree of subconscious self-hatred that may exist in a religious person who taunts an atheist with being no better than a believer!whereas the person of faith must aver not only that there is a god, but that this gods wishes and desires may be known. It can be stated confidently, for example, that he hates hams and clams and was otherwise engaged when homosexuals (who are somehow against nature) were created. In other words, the less evidence we possess, the more absolutely sure we must be.

Certitude of this kind is by no means to be envied, and those who have for years been relishing Edward Sorels occasional cartoon-update Religion in the News will know what a rich seam of absurdity and worse can be mined from the credulous. (Credulous means, really, one who craves certitude.) Many of this fine books prime exhibits are necessarily also of the faith-based sort, and when confronted with the claims of such jackasses and poltroons it is always wise to keep in mind the work of David Hume on miracles. When confronted with an apparent miracle, remarked the great Scottish philosopher, it is prudent to ask oneself which is more likely: that the rules of nature have been suspended or that you yourself are under a misapprehension. Doubt, in such an instance, is the minds best friend. Certitude, by contrast, betrays the wish to be mindless. The case of Sir Arthur Conan Doyles unshakeable belief in fairies is not precisely an instance of religious tomfoolery but does show that certain kinds of belief are evidence-proof. The actual case was even more bizarre than Adam Begley has room to say; even the good folks at Kodak declared themselves taken in by the pathetically obvious darkroom hoax. The most sorry illusions and delusions have a way of spreading in a way that, alas for suffering humanity, cannot be copied by moments of lucidity.

Lets not be snobbish about the deluded. There may be crowds of what H.L. Mencken called boobs, who will stand in line to buy colored medicine water and let their jaws hang low at apparitions of the Virgin. But the great William Butler Yeats was never happier than at spiritualist sances that featured burblings (and scribblings) from the beyond. The hardheaded Henry Ford was an abject pushover for that preposterous hoax The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion, and not only fell for it himself but invested a huge tranche of valuable capital in trying to get others to become true believers, too. By the way, congratulations to Begley for getting this right and describing the Protocols as a hoax: They are too-often referred to as a forgery whereas a forgery is a copy of something authentic, and not a mere fabrication.

When you have finished scanning David Hume on miracles you might like to take up Richard Hofstadters work on The Paranoid Style in American Politics. Here you will find the best definition of the paranoid that I have yet read: a man who already has all the information he needs. Again in these pages you will be put in mind of the phenomenon, and again you will find that much of the pathology is faith-based. Did Elijah Muhammad have to prove that every blue-eyed white devil actually possessed blue eyes? Not really. Best to regard it as a metaphor. But would he revisit the general, overarching theory that all whites of all eye colors were essentially diabolical? Never!

S omething of the same effect can be observed with the infallibility concept. This higher by-product of certitude means that it can be very difficult to correct a mistake. In my own lifetime I have seen a series of popes make public apologies to Jews (for the false charge of deicide and its consequences), to Protestants (for the Counter-Reformation), to Galileo, to forcibly converted and exterminated South American Indians, to Eastern Orthodox Christians (for the massacres in the Balkans), and to Muslims (for the Crusades). But having made these little course-corrections, inevitable perhaps in the life of a one true Church, the Vatican is now ready to go back to being infallible all over again. So that one day ifjust supposeit is discovered that AIDS was a worse affliction than the condom, rather than the other way around, the necessary admission will have to be delayed for years by the fact that there was once a sacred dogma involved.

Nobody likes a ditherer. Both military and political leadership are best exercised by people who can make a decision and stick to it, rather than (as was once said of Lord Derby) like a cushion, bear the impression of whoever last sat upon him. However, a decided leader who does not listen to the doubts of others as well as his own may well become famous for other reasons. From George Armstrong Custer to the teak-headed British generals on the Western Front, we have shining examples of those who kept doing the same old thing, each time hoping for a different result. This conforms to George Santayanas definition of fanaticism, which is redoubling your efforts when you have forgotten your aims. Only the wonderful consolation of knowing that you were right all along can get you through an ordeal like that. If it were not so, there would be no memoir industry and no second act racket in which gruesome exhibits like the new Nixon can be dragged onto the amphitheaters already bloodstained sand.

I have some Humean disagreements with the authors here. (Which is more likely, that a Saddam Hussein who had both used and concealed WMDs would be telling the truth just for once, or once again concealing his hand?) But thats because I think the same standard should apply to everyone, including myself. One day, perhaps, the Virgin Mary will appear in blue raiment with good visibility and on camera to a large throng of adult non-Catholics, and will speak intelligible words. On that day, if I am present, I will be inclined to think that I am suffering from an individual or collective hallucination. In fact, on balance, Ill be absolutely sure of it.

To be positive: to be mistaken

at the top of ones voice.

A MBROSE B IERCE

Convictions are more dangerous

enemies of truth than lies.

F RIEDRICH N IETZSCHE

Doubt is not a pleasant condition,

but certainty is an absurd one.

V OLTAIRE

Pope Urban II

(104299)

O n November 27, 1095, the tenth day of the Council of Clermont, Pope Urban II (a.k.a. Otho, Otto, or Odo of Lagery) gave a sermon historians now consider one of the most important in the history of Europe. By declaring a bellum sacrum (what Muslims call jihad) against the infidels occupying the Holy Land, he launched the First Crusade, a bloody rampage through Europe and Asia Minor, which, unlike subsequent crusades, actually achieved its purpose: to regain control of Jerusalem. The crusaders celebrated the capture of the Sacred City with a comprehensive, notoriously ferocious massacre of all its inhabitantsMuslims, Jews, and even a few stray Christians.