Charles Lindbergh, Dr. Alexis Carrel, and Their Daring Quest to Live Forever

David M. Friedman

Maralin R. Friedman

Contents

I Will Show You What Im Doing Here

If Man Could Learn to Fly

A Student Who May Amount to Something

Isnt He in the Crib?

The Chamber of Life

Every Act of His Is Not a Fluke

Men of Genius Are Not Tall

A Tiny Puff of Smoke

The Most Interesting Place in the World Today

The Exploration of This Realm Is a Great New Adventure

The Reaction of a Man Would Probably Be Similar

Two Men Sitting on Two Rocks

By Order of the Fhrer

Ill Take a Rain Check

Not Merely a Schoolboy Hero, but a Schoolboy

For We All Know What Awaits Us

There Is Much I Do Not Like That Is Happening in the World

The Tissues, the Blood, and the Mind of Man

The World Was Never Clearer

The Grandeur of His Life

I Felt the Godlike Power

Only by Dying

No, Science Has Abandoned Me

All of Us Are Following

I WILL SHOW YOU WHAT IM DOING HERE

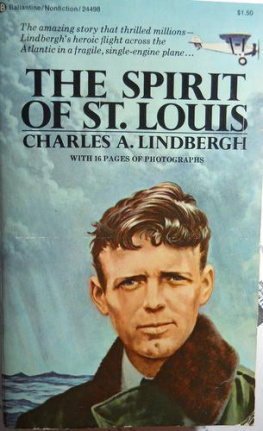

C HARLES LINDBERGHS FAMILIARITY WITH PRYING GAZES began on May 21, 1927, the day he became the most famous man in the world. That status was conferred on the unsuspecting twenty-five-year-old, literally overnight, when he was the first aviator to fly without stopping from New York to Paris, a feat that many peopleeven many aviatorshad thought impossible. Making Lindberghs triumph all the more newsworthy was that he flew without a copilot, a radio, or even a front window for thirty-three and a half hours in a single-engine airplane made from wood, canvas, and piano wire. The New York Times showed its awe by devoting its first five pages to the dimple-chinned Americans landing at Le Bourget, the dusty airfield where 100,000 Frenchmennearly all of them chanting LAN-BAIRGH! LAN-BAIRGH !were so eager to stare at the spent pilot that they almost trampled him to death after he climbed out of his cockpit. Maintenance crews swept up a ton of personal items lost or abandoned in that lovefest, including a sable coat and six sets of false teeth.

In the week that followed, Lindbergh, in new clothes made by a Paris tailor, was seen by the president and premier of France, the French chamber of deputies, and a million more Frenchmen who lined a parade route along the Champs-lyses. After leaving France he was presented to the king of Belgium, the king of England (who asked, How did you pee?), and the prince of Wales (the future duke of Windsor), whom Lindbergh quickly replaced as the most photographed person on earth. Returning home, he was gawked at by 300,000 Americans at the Washington Monument, where President Coolidge pinned the Distinguished Flying Cross on his chest. Four million New Yorkers showered him with cheers and paper scraps, as 10,000 schoolchildren sang Hail the Conquering Hero Comes, in the largest ticker-tape parade the world had ever seen. Taking a three-month victory lap, Lindbergh flew his plane, the Spirit of St. Louis , to every state in the union; rode in 1,300 miles of motorcades; gave 147 speeches; and was seen, in the flesh, by 30 million peopleone out of every four Americans then living. Still, none of this prepared Lindbergh for the way he was stared at on November 28, 1930, the day the worlds most famous man was introduced to the person some considered the worlds smartest.

Ironically, that day began with steps aimed at preventing Lindbergh from being stared at. Before entering his black Franklin sedan outside his rented home in Princeton, New Jersey, Lindbergh slipped a pair of lensless eyeglasses over his famously blue eyes and a fedora hat over his equally famous blond hair. Much to his pleasure, hed found this simple disguise was usually enough to afford him some privacy in public. Privacy was always important to Lindbergh, but it was crucial this morning because he wanted to think quietly in his car as he made the two-hour drive into New York, without interruptions from starstruck toll takers or fellow motorists. What Lindbergh wanted to think about was the list of questions he planned to ask the man he was driving to meet, a man whose name hed only recently heard for the first time.

He heard it from Dr. Paluel Flagg, the anesthetist who attended Lindberghs wife, the former Anne Morrow, when she gave birth to the Lindberghs first child, Charles Jr., on June 22, 1930. Lindbergh had met his wife in December 1927 when he flew to Mexico City, an event that caused nearly as much pandemonium as his landing in Paris. Anne, then an introverted twenty-one-year-old college student, was worried at first that her Christmas holiday with her family at the U.S. embassyher father, Dwight, was the American ambassadorwould be spoiled by the presence of someone she called a sort of baseball player.

But that anxiety vanished when the tall, handsome aviator took the ambassadors middle daughter on her first airplane flight, a thrill that Anne, a short brunette unsure of her own attractiveness, described in her diary in near-orgasmic terms. Lindbergh moved so very little in the cockpit, yet you felt the harmony of it, she wrote. It was a complete and intense experience. The pilot and his sated passenger were married on May 27, 1929, in a secret ceremony at Next Day Hill, the Morrow family mansion set on a verdant fifty-acre estate overlooking the Hudson River in Englewood, New Jersey. Most of the two dozen guests thought theyd been invited to play bridge.

When Anne went into labor in the same mansion the next summer, her husband, waiting in the next room, struck up a conversation with Dr. Flagg. The topic was Annes older sister Elisabeth, whose health had deteriorated dramatically after a bout of rheumatic fever damaged her hearts mitral valve, the valve that regulates the flow of blood from the left atrium into the left ventricle, the hearts main pumping chamber.

Lindbergh, who knew a fair bit about valves in machines, was puzzled that a mere valve in the heartthe bodys engine, as he saw itcould cause so much trouble in an otherwise vibrant woman in her mid-twenties. He was similarly vexed to learn that not one of the doctors consulted by Elisabeths family, several of whom Lindbergh had questioned personally, had any ideas on how to proceed. Lindbergh had several: remove and replace the broken valve, as he would do in an airplane engine; replace the entire heart with a mechanical pumpan artificial heart, he called itjust as Lindbergh would replace a failed airplane motor; or insert a temporary blood pump, remove the heart, fix it, then put it back.

Lindbergh spoke to Flagg about Elisabeth Morrows situation because he noticed that the anesthetist had brought with him a machine he invented to give artificial respiration to newborns, in case a breathing emergency arose with the Lindberghs baby. Fascinated by all things mechanical, Lindbergh asked for permission to examine the device, which was made of an oxygen tank, a pressure regulator, and several feet of rubber tubing.

Would you show me how it works? he asked.

Of course, Flagg said.

After the demonstration, which filled the room with the sound of rushing gas, Lindbergh thought hed finally found a doctor who would take his bioengineering ideas seriously. He was right about that, but Flagg didnt think his own specialized training in anesthesiology gave him the expertise to address the complex surgical issues raised by Lindberghs ideas.

But I know someone who could, he said: a Nobel Prizewinning surgeon Flagg once served as an intern in New York. The surgeons name, he said, was Alexis Carrel.