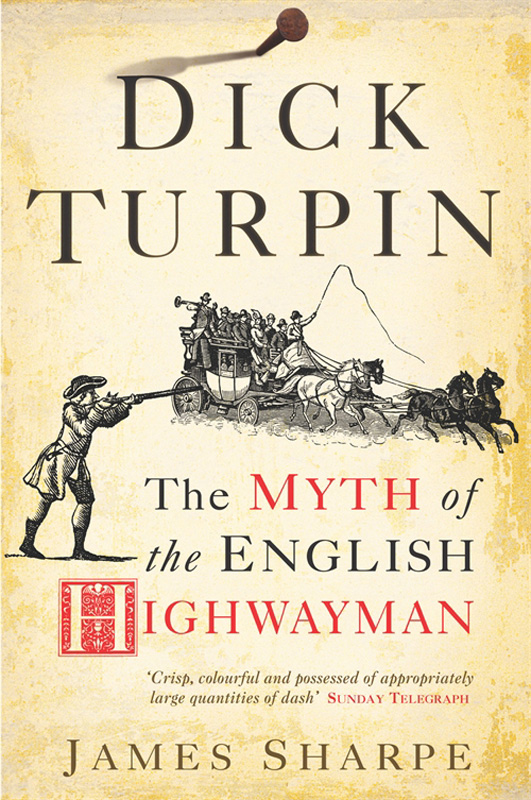

DICK TURPIN

James Sharpe is Professor of History at York University and is a leading expert on the history of crime in pre-modern England. He was a founder member of the International Association for the History of Crime and Criminal Justice, and currently serves on its committee. He has also acted as director for an Economic and Social Research Council-funded project on the history of violence in England, 16001800. Previous publications include Crime in seventeenth-century England: a County Study, and TheBewitching of Anne Gunter (Profile). He is married with two children.

DICK TURPIN

The myth of the

English highwayman

JAMES SHARPE

This paperback edition published in 2005

First published in Great Britain in 2004 by

Profile Books Ltd

58a Hatton Garden

London EC1N 8LX

www.profilebooks.co.uk

Copyright James Sharpe, 2004, 2005

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Typeset in Poliphilus by MacGuru

info@macguru.org.uk

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

Bookmarque Ltd, Croydon, Surrey

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available

from the British Library.

eISBN: 978-1-84765-114-3

For Freddie

As a warning against bad men

CONTENTS

D ick Turpin has been in my thoughts for a long time. My first researches as a historian of crime were carried out on seventeenth-century England, but from an early stage I broadened out, backwards into the late sixteenth century, and forwards into the early eighteenth. Both of these periods, as far as criminality is concerned, have their distinctive features. Those of the late sixteenth century need not detain us. Those of the early eighteenth include, firstly, insofar as we can reconstruct these things, changes in patterns of crime; secondly, and more certainly, changes in punishment, and hence, thirdly, changes in official perceptions of how crime might be combated. And, fourthly, changes, connected with an explosion in printed materials, in how crime and criminals were portrayed in the books, pamphlets, plays and newspapers of the period. From an early stage it struck me that the criminal career, trial, and execution of Dick Turpin drew a number of these themes together.

This feeling became deeper, and much better informed, when I had to focus my ideas on Turpin after agreeing in the late 1980s to give a lecture on him in one of York Universitys Open Course Lecture Series. This also introduced me to William Harrison Ainsworth, the man who, roughly a century after Turpin was executed, created the mythical Turpin who is currently a much more familiar figure than the historical one. Pursuing this theme further, and giving the occasional public talk on Turpin and the Turpin legend, not only convinced me of the interest of the theme, but also led me to ponder on how the disjuncture between the historical and the mythical Turpin, and the way in which Englands best-known highwayman was constantly being recreated, reflected on the uses and meanings of history in modern Britain. Writing a book on Turpin seemed the only way to get historys most famous Essex Man off my mind.

While putting this book together I have benefited from the resources, and the helpfulness of the staff, of the British Library, the J. B. Morrell Library of the University of York, York Minster Library, the Gurney Library of the Borthwick Institute of Historical Research, York, the Public Record Office, London, York City Archives, the East Riding Archive Office, the Essex Record Office, and York Castle Museum. I have also benefited from correspondence with that great Turpin scholar, Derek Barlow. Once again, my wife, Krista Cowman, has been a source of support and advice.

I have decided to dispense with a formal structure of footnotes in this book, but any interested reader can follow the sources I have used by examining the notes and references at its end.

And, finally, a personal observation. Although I am not a native of that part of the country, I began my career as a historian working on the archives of the county of Essex. There is, as I write, every probability that I will end that career at York. There is a certain irony that, even if I have not exactly followed either Dick Turpins footsteps or Black Besss hoofprints, my professional life has followed a similar geographical trajectory to that of the man whose career and later reputation form the subject matter of this book.

Stillingfleet, North Yorkshire

chapter one

YORK, APRIL 1739

A t least he died well, in what the eighteenth century considered the appropriate manner for its condemned criminals. Determined to look his best when he met his end, he had, a few days previously, bought himself a new frock coat and a pair of pumps. He had also, as a further preparation, on the day before his execution appointed five men as his mourners, and given them three pounds and ten shillings to be shared among them for following the cart that would carry him to the gallows and for overseeing his subsequent interment. He distributed hatbands and gloves to several other people, and left a gold ring and two pairs of shoes and clogs to a married woman with whom he had consorted, despite reports that he had a wife and child living in the south, while he lived under an assumed identity at the Humberside township of Brough.

On Saturday 7 April, the day of execution, he was carried in a cart, his mourners behind him, from the county gaol at York Castle through the centre of the city, up Micklegate, through Micklegate Bar, and on to what a contemporary source describes as a fair broad street, well paved on both sides; in fact, the first few hundred yards of the road to Tadcaster. He was accompanied in the cart by the other man sentenced to death a fortnight previously at the Yorkshire assizes, John Stead, like him convicted for horse-stealing. Of John Stead we know little. But Steads companion in the cart, up to a few weeks before known to his captors as John Palmer, was a rather more significant figure: the notorious highwayman Richard Turpin, a year or two previously Englands most wanted criminal, with a 200 reward for murder on his head. Sir George Cooke, sheriff of Yorkshire and the official responsible for the smooth running of the execution, was later to claim twenty pounds in expenses for conveying Turpin and Stead under a strong guard to the place of execution, evidence of concern over an attempted escape or rescue. In the event, such worries proved misplaced. Turpin, so the description of his execution tells us, acted out the role fate had allotted to him, behavd himself with amazing assurance, and bowd to the spectators as he passed. His and Steads last morning was probably a cold one: certainly Arthur Jessop, an apothecary living at Wooldale over in the West Riding, had noted in his diary that the previous day had seen a blustering cold wind, rain hail and snow. But, despite the circumstances, Turpin was evidently determined to die game.