Acclaim forDavid Remnicks

KING OF THE WORLD

Remnick brings to his reading of the Ali scriptures a helpful sense of recent boxing history, inseparable from political history. It doesnt read like the case history of the man (though the man is here in living colors, sometimes funny as hell), but of a comic and cosmic superman.

Budd Schulberg, The New York Times Book Review

It may prove to be a classic. Beautifully reported, compelling.

New York Daily News

Of the many books about Ali, [this] seems the closest to illuminat[ing] the complexities of the man.

The Washington Post Book World

Deftly told a clear, well-written portrait.

St. Louis Post-Dispatch

Remnick shines a brilliant light on the myth and the man.

Elle

An engrossing and important book. The fight scenes are absolutely rivetingwritten with an excitement and an immediacy that only someone who loves his subject can consistently pull off.

National Review

David Remnick

David Remnick was a reporter for The Washington Post for ten years, including four in Moscow. He joined The New Yorker as a writer in 1992 and has been the magazines editor since 1998.

Books by David Remnick

Lenins Tomb: The Last Days of the Soviet Empire

The Devil Problem and Other True Stories

Resurrection: The Struggle for a New Russia

King of the World

FIRST VINTAGE EBOOKS EDITION, OCTOBER 1999

Copyright 1998 by David Remnick

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House LLC, New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto, Penguin Random House companies. Originally published in hardcover in the United States by Random House LLC, New York, in 1998.

Vintage and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material:

James Baldwin Estate: Excerpt from The Fight: Patterson vs. Liston by James Baldwin, originally published in Nugget. Copyright 1963 by James Baldwin. Copyright renewed. Reprinted by arrangement with the James Baldwin Estate. / Playboy: Excerpt from The Playboy Interview: Cassius Clay (October 1964). Copyright 1964 by Playboy; excerpt from The Playboy Interview: Muhammad Ali (November 1975). Copyright 1975 by Playboy. Reproduced by special permission of Playboy magazine. / Simon and Schuster: Excerpts From Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times by Thomas Hauser. Copyright 1991 by Thomas Hauser and Muhammad Ali. Reprinted by permission of Simon and Schuster. / Gay Talese: Excerpt From The Loser by Gay Talese. Originally published in Esquire magazine. Copyright 1962 by Gay Talese. Excerpt from In Defense of Cassius Clay by Gay Talese. Originally published in Esquire magazine. Copyright 1966 by Gay Talese. All excerpts reprinted by permission of the author. / The Wylie Agency: Excerpt from Ten Thousand Words a Minute by Norman Mailer. Copyright 1963 by Norman Mailer, first printed in Esquire magazine. Reprinted with the permission of The Wylie Agency.

eBook ISBN: 978-0-8041-7362-9

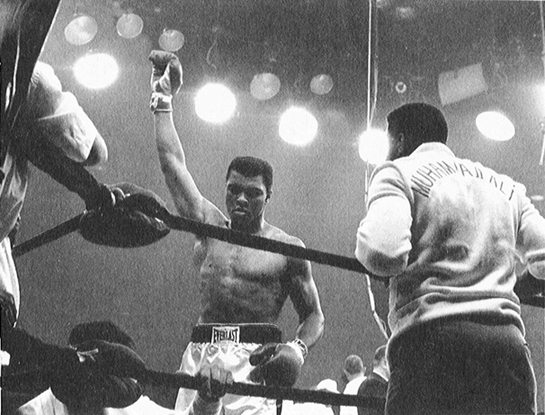

Frontispiece photograph by Howard L. Bingham

www.vintagebooks.com

Cover design by John Gall

Cover image Chris Smith/Getty Images

v3.1

For my brother, Richard,

and for my friend Eric Lewis

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE: IN MICHIGAN

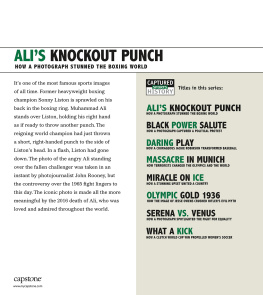

Cassius Clay entered the ring in Miami Beach wearing a short white robe, The Lip stitched on the back. He was beautiful again. He was fast, sleek, and twenty-two. But, for the first and last time in his life, he was afraid. The ring was crowded with has-beens and would-bes, liege men and pugs. Clay ignored them. He began bouncing on the balls of his feet, shuffling joylessly at first, like a marathon dancer at ten to midnight, but then with more speed, more pleasure. After a few minutes, Sonny Liston, the heavyweight champion of the world, stepped through the ropes and onto the canvas, gingerly, like a man easing himself into a canoe. He wore a hooded robe. His eyes were unworried, and they were blank, the dead eyes of a man whod never gotten a favor out of life and never given one out. He was not likely to give one to Cassius Clay.

Nearly every sportswriter in the Miami Convention Hall expected Clay to end the night on his back. The young boxing beat writer for The New York Times, Robert Lipsyte, got a call from his editors telling him to map out the route from the arena to the hospital, the better to know the way once Clay ended up there. The odds were seven to one against Clay, and it was almost impossible to find a bookie willing to take a bet. On the morning of the fight, the New York Post ran a column written by Jackie Gleason, the most popular television comedian in the country, that said, I predict Sonny Liston will win in eighteen seconds of the first round, and my estimate includes the three seconds Blabber Mouth will bring into the ring with him. Even Clays financial backers, the Louisville Sponsoring Group, expected disaster; the groups lawyer, Gordon Davidson, negotiated hard with Listons team, assuming that this could be the young mans last night in the ring. Davidson hoped only that Clay would emerge alive and unhurt.

It was the night of February 25, 1964. Malcolm X, Clays guest and mentor, was at ringside, in seat number seven. Jackie Gleason and Sammy Davis were there, and so were the mobsters from Las Vegas, Chicago, and New York. A cloud of cigar smoke drifted through the ring lights. Cassius Clay threw punches into the gray floating haze and waited for the bell.

S EE THAT ? S EE ME ?

Muhammad Ali sat in an overstuffed chair watching himself on the television screen. The voice came in a swallowed whisper and his finger waggled as it pointed toward his younger self, his self preserved on videotape: twenty-two years old, getting warm in his corner, his gloved hands dangling at his hips. Ali lives in a farmhouse in southern Michigan. The rumor has always been that Al Capone owned the farm in the twenties. One of Alis dearest friends, his cornerman Drew Bundini Brown, had once searched the property hoping to find Capones buried treasure. In 1987, while living in a cheap motel on Olympia Avenue in Los Angeles, Bundini fell down a flight of stairs. A maid finally found him, paralyzed, on the floor; he died three weeks later.

Now Ali was whispering again, See me? You see me? And there he was, surrounded by his trainer, Angelo Dundee, and Bundini, moon-faced and young and whispering hoodoo inspiration in Alis ears: All night! All night! Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee! Rumble, young man, rumble!

Thats the only time I was ever scared in the ring, Ali said. Sonny Liston. First time. First round. Said he was gonna kill me.

Ali was heavy now. He had the athletes disdain for exercise and ate more than was good for him. His beard was gray and his hair was going gray, too, Id come up to Michigan to see him because I wanted to write about the way hed created himself in the early sixties, the way a gangly kid from Louisville managed to become one of the most electric of American characters, a molder of his age and a reflection of it. As Cassius Clay, he entered the world of professional boxing at a time when the expectation was that a black fighter would behave himself with absolute deference to white sensibilities, that he would play the noble and grateful warrior in the world of southern Jim Crow and northern hypocrisy. As an athlete, he was supposed to remain aloof from the racial and political upheaval going on around him: the student sit-ins in Nashville in 1960 (the year he won a gold medal in Rome), the Freedom Rides, the march on Washington, and the student protests in Albany, Georgia, and at Ole Miss (as he was making his way up the heavyweight ladder). Clay not only responded to the upheaval, he responded in a way that outraged everyone from white racists to the leaders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. He changed his religion and his name, he declared himself free of every mold and expectation. Cassius Clay became Muhammad Ali. Nearly every American now thinks of Ali with misty affectionparadoxically, he was a warrior who came to symbolize lovebut that transformation in the popular mind came long after Alis period of self-creation in the early sixties, the period covered in this story.