Acclaim for

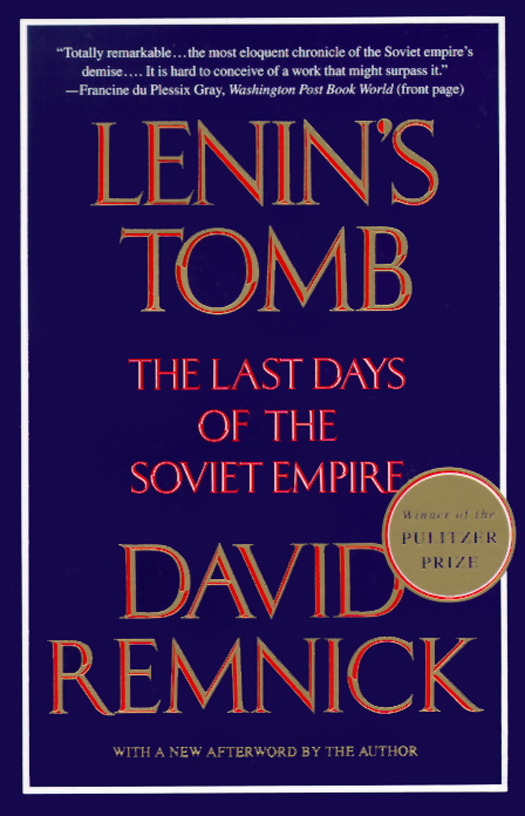

DAVID REMNICKS

LENINS TOMB

An eloquent and riveting oral history of an epochal moment of change.

Michael Ignatieff, Los Angeles Times

Remnick is an observer of great scope. He writes with enormous ease, and the humor and honesty of a modern de Tocqueville.

Christian Science Monitor

A superbly reported account of the fall of the Soviet Empire.

U.S. News and World Report

Remnick has written what may be the definitive narrative of the last days of the Soviet Union. [Lenins Tomb] is a history that combines old-fashioned narrative of great events with the more fashionable approach of describing common lives. It succeeds smashingly.

Birmingham News

Always vivid, often funny, sometimes moving.

USA Today

David Remnick has written one hell of a book.

Baltimore Sun

A riveting account of the unraveling of the Soviet Union Lenins Tomb reads like a novel. Mr. Remnick develops with artistry and compassion a handful of characters who best reflect the themes of the waning years of Soviet rule.

Atlanta Journal-Constitution

David Remnick has produced a prodigious and fascinating account of what it was like to witness the collapse of both an empire and its imperial history. It is difficult to imagine anyone writing about the disintegration of the USSR more graphically, more intimately or more comprehensively.

Wisconsin State Journal

Remnicks gripping and valuable first reading of events is destined to achieve a permanent place in the literature of Russian history.

Kansas City Star

Lenins Tomb is touching, witty, and informative.

Raleigh News & Observer

Remnick has given us a book that is essential reading for anyone interested in the final years of the Soviet Union. It should not be missed.

Wichita Eagle

David Remnick

David Remnick was a reporter for The Washington Post for ten years, including four in Moscow. He joined The New Yorker as a writer in 1992 and has been the magazines editor since 1998.

FIRST VINTAGE EBOOKS EDITION, MAY 1994

Copyright 1993, 1994 by David Remnick

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House LLC, New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto, Penguin Random House companies. Originally published in hardcover in slightly different form in the United States by Random House LLC, New York, in 1993.

Vintage and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material: Martin Secker & Warburg Ltd: Thirty-two lines from Requiem from You Will Hear Thunder by Anna Akhmatova, translated by D. M. Thomas. Copyright 1976, 1979, 1985 by D. M. Thomas. Reprinted by permission.

eBook ISBN: 978-0-8041-7358-2

www.vintagebooks.com

Cover design by John Gall

v3.1

to my parents

and to Esther

CONTENTS

PREFACE

Long before anyone had a reason to predict the decline and fall of the Soviet Union, Nadezhda Mandelstam filled her notebooks with the accents of hope. She was neither sentimental nor naive. She had seen her husband, the great poet Osip Mandelstam, swept off to the camps during the terror of the 1930s; she described in ruthlessly clear terms how the regime left its subjects in a permanent state of fear. The people of the Soviet Union had been made, as she put it, slightly unbalanced mentallynot exactly ill, but not normal either. But Mandelstam, unlike so many scholars and politicians, saw the signs of the Soviet systems inherent weakness and believed in the resiliency of the people.

On August 20, 1991, a rainy, miserable afternoon, I walked among the crowds protecting the Russian parliament from a potential invasion by the leaders of a military coup. We all saw that day what so few could have predicted: Soviet citizensworkers, teachers, hustlers, children, mothers, grandparents, even soldiersall standing up to a group of ignorant men who believed themselves yet another improved version of the Bolshevik regime and possessed of a power to freeze, even turn back, time. In their hurried calculations, the conspirators assumed the masses were too exhausted and indifferent to fight back. But tens of thousands of ordinary Muscovites were ready to die for democratic principles. It was said then and is said even now that the Russians know little or nothing of civil society. How strange, then, that so many were willing to give up their lives to defend it.

I do not usually have a great memory for the things I have read, but that afternoon of the coup, hours before it came clear that there would be no attack and the putsch would fail, I thought of a short passage, bracketed in black, in my paperback copy of Nadezhda Mandelstams Hope Against Hope: This terror could return, but it would mean sending several million people to the camps. If this were to happen now, they would all screamand so would their families, friends and neighbors. This is something to be reckoned with. The leaders of the August coup had not reckoned with the development of their own people. They understood nothing. They were jailed for the miscalculation, and the struts of the old regime collapsed.

As I write, the euphoria of those August days is past and Russian democracy is a delicate thing. There are days when it seems that little has changed, that the fate of Russia hinges, once more, on the skills, inclinations, and heartbeat of one man. This time it is Boris Yeltsin: heroic during the coup, flexible, clever, but also, at times, reckless with language, careless with the bottle. No one knows what would happen should Yeltsin fall from power, the result of a stroke or an uprising of the hardline nationalists, neofacists, and nostalgic Communists who dominate parliament. As this book goes to press in April 1993, the power struggle between Yeltsin and parliament is unresolved and has underscored the lack of a clear and workable constitution, legal system, and system of authority. The institutions of this new society are embryonic, infinitely fragile.

In January 1993, Yeltsins program of economic shock therapy has resulted in only fitful progress, much pain, and, everywhere, anxiety. Food and other supplies are in some places more plentiful, but prices are out of control. The inflation rate is beginning to look Latin American. The heads of the vast military plants show little interest in converting to a peacetime economy, and the absurd subsidies they receive make a mess of Russias finances. A brash new class of young hustlers and even some honest businesspeople are thriving, but the old, the weak, and the poor are despondent. The crime rate is out of control. And everywhere there is a new demagogueCommunist, nationalist, or simply madready to exploit the failures, vanities, and misfortunes of the elected government. The danger of the authoritarian temptation still lurks in Russia. So far, nearly all the potential successors to Yeltsin promise to be less inclined to radical economic reform and more likely to carry out an aggressive anti-Western foreign policy.