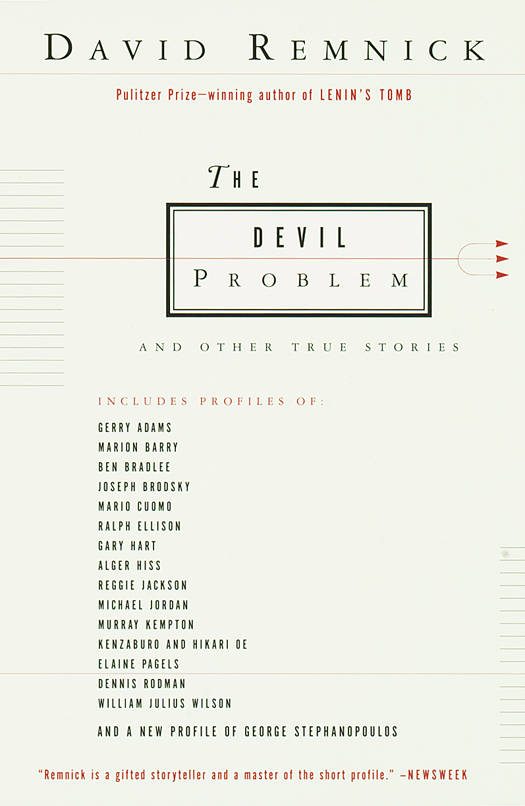

Acclaim forDavid Remnickand

The Devil Problem

Delightful. Remnick is a master of delivering us to the heart of the life hes examining.

Denver Post

Wonderfully moving edifying.

Los Angeles Times Book Review

Highly recommended for its graceful prose and perceptive insights into the lives of prominent people and the culture of celebrity more generally.

Cleveland Plain Dealer

Simply remarkable. Remnick is a careful reporter, a clear stylist, a writer who is both incisive and funny.

New Orleans Times-Picayune

Remnick is an observer of great scope. He writes with enormous ease, and the humor and honesty of a modern de Tocqueville.

Christian Science Monitor

Here is a writer who has the ace reporters nose for a good story, and the cultural range and fluency of a classical belleslettrist. I find his work unfailingly interesting. He is a pleasure to read.

E. L. Doctorow

David Remnick is a marvelone of the signature figures in a wonderful new generation of nonfiction writers.

David Halberstam

David Remnick is an acute observer of the small movements of life.

Janet Malcolm

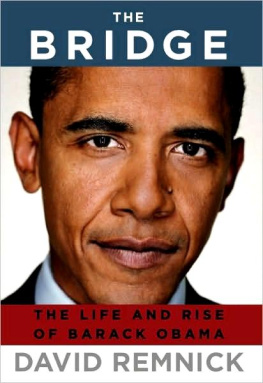

Books byDavid Remnick

Lenins Tomb: The Last Days of the Soviet Empire

The Devil Problem and Other True Stories

Resurrection: The Struggle for a New Russia

David Remnick

David Remnick was a reporter for The Washington Post for ten years, including four in Moscow. He joined The New Yorker as a writer in 1992 and has been the magazines editor since 1998.

Copyright 1996, 1997 by David Remnick

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House LLC, New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto, Penguin Random House companies. Originally published in slightly different form in hardcover in the United States by Random House LLC, New York, in 1996.

Vintage and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

The essays in this work have been previously published in Esquire, The New Yorker, and The Washington Post.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material:

Farrar, Straus & Giroux, Inc.: Excerpt from Lullaby on Cape Cod from A Part of Speech by Joseph Brodsky. Translation copyright 1980 by Farrar, Straus & Giroux, Inc. Excerpt from Uncommon Visage: The Nobel Lecture from On Grief and Reason by Joseph Brodsky. Copyright 1995 by Joseph Brodsky. Reprinted by permission of Farrar, Straus & Giroux, Inc. Murray Kempton: Excerpts from America Comes of Middle Age by Murray Kempton. Reprinted by permission of the author. Random House, Inc: Eight lines from In Memory of William Butler Yeats from Collected Poems by W. H. Auden. Excerpt from Shadow and Act by Ralph Ellison. Reprinted by permission of Random House, Inc. Zephyr Press: Four lines from I dont weep for myself now , from The Complete Poems of Anna Akhmatova, Vol. II, translated by Judith Hemschemeyer (1990). Copyright 1990 by Judith Hemschemeyer. Reprinted by permission of Zephyr Press, Somerville, Massachusetts.

eBook ISBN: 978-0-8041-7363-6

www.vintagebooks.com

Cover design by Abby Weintraub

v3.1

For Alex and Noah and, always, Esther

PREFACE

We order and excite our mental lives with stories. Mostly, they are the same stories over and over again. The tabloids (in print and, now, on television) have their set of stories: the wealthy brought low, betrayal in marriage and commerce, the murder of the innocent, the humbling of the celebrity, the ordinary mans triumph. They differ from the novels of, say, Dreiser, or the plays of Shakespeare, in the richness of detail, the complexity of thought and incident, the wealth of language, but in the story of O. J. Simpson (the tabloid story of the millennium) there were surely elements of An American Tragedy and Othello. There are other textures of mental lifethe analytical, the pure emotions of lust or ragebut stories, the telling and listening, are much of what we are.

Reporters are interested in amassing information, in sorting through the latest trends, but above all we are interested in stories. They often contain useful information, but they are also patterns, morality plays, entertainments. To me, at least, Gary Harts exile from public life after scandal drove him out of the 1988 presidential race is a story out of Dreiser, too. (It is surely a story that influenced the way Bill Clinton told his story a few years later.) Ralph Ellisons excruciating attempt, over many decades, to write a second novel after the great success of his first, Invisible Man, is a story. There is something Greek about Ellisons tragedy, the way a manuscript (with no copy) burned in a house fire, the way he died, a couple of weeks after talking with me, having left his novel, fragmented, incomplete, in the hands of others. How a great religious historian, Elaine Pagels, comes to write about evil and the devil after the death of her husband and son is a story about the way thought and creation begin.

The real subjects of these storiesthe politicians, the scholars, the artists, the athletesdo not necessarily recognize themselves in the way they are depicted here. They dont see in the published result the fullness of themselves and their experience. I dont blame them. Journalism is not allowed the liberties of the novel or the evidence of the psychiatric dossier. Stories can only be a part, a glimpse, of that fuller thing, the life.

Even though I am sure a number of the subjects of these pieces were not at all pleased with the resultI dont expect another dinner invitation from Gary Hart, and Gerry Adams never sent a thank-you noteI am grateful to all of them. Janet Malcolm is dead right when she describes how the subjects of journalism so often feel taken in when they discover that the story that comes out in the end is not necessarily the story as they had pictured it in their heads. The writer, and not the subject, chooses the details that will go into the pieces and what ought to be ignored as irrelevant or dull.

In defense of these stories, the reader should know they are true. Or, better to say, factual. These pieces range over many fields of lifepolitics, scholarship, literature, sportsand touch on the problems of race, sex, jealousy, aging, exile, and terror. But mostly, they are about the gap between private life and public ambition, the strange decisions someone like Gary Hart and Mario Cuomo will make when faced with the possibility of becoming a president or a justice of the Supreme Court; how Alger Hiss lives out his life when part of the world regards him as a pariah, another as a martyr; how an athlete faces the death of retirement; how two obscure scholars react when their relationship collapses into acrimony over a theory that both are convinced will revolutionize Shakespeare studies. The facts in all of them are straight, or at least the best I could do. In any case, I had the benefit of a ten-year-long apprenticeship at The Washington Post, the indulgence of the editors of The New Yorker