Bowfin

Amia calva

Local Names: Mudfish, Dogfish, Grindle, Grinnel, Cypress trout, Blackfish

Distinguishing Field Marks:

- Thick robust body, nearly cylindrical in cross-section.

- A long, single, soft-rayed dorsal fin originates above the mid-point between the pectoral and pelvic fins.

- Two short barbels at the tip of the snout.

- Males usually have a nearly black spot haloed in yellow or orange at the base of the upper caudal (tail) fin.

- In adult females, the black spot is not haloed or may be absent.

- A terminal mouth armed with many large strong teeth, which should always be given the utmost respect by anglers.

Average Size:

18 to 28 inches (45.70 to 71.10 cm)

5 to 9 pounds (3.20 to 4.10 kg)

Biology:

In April, May, and June, depending on latitude and water temperature, adult male bowfin clear nests in weedy still-water areas by biting and rubbing against the bottom vegetation. On completion of these nests, ripe females join the males and deposit fertilized eggs into the nest. Spawning completed, the females move off to feed while the males guard the egg-filled nests through their typical 8- to 10-day incubation period. Guarded by the male parent, newly hatched bowfin are equipped with an adhesive organ on their snouts. These are used to attach themselves to any surrounding structure where they take what appropriate food comes their way. When they are of sufficient size, they begin free-swimming and feeding over the nest, which they eventually leave in a compact school, attended by the male parent until they are able to entirely fend for themselves and adopt the solitary lifestyle of adult bowfin.

As adults, bowfin tend to spend daylight hours in deeper water, moving into the shallows after dark to feed. In hot weather they will often rise to the surface to gulp air and, in winter in colder regions, will congregate in whatever areas remain ice-free to allow them to continue this oxygen replenishment behavior.

Diet:

The primary diet of adult bowfin is fish and crayfish, but, like all warm-water species, bowfin are opportunists and will take whatever food presents itself.

Locating and Fishing for Bowfin:

Although their shallow-water preference is primarily nocturnal, bowfin can often be seen lazily finning in weedy shallows in daylight hours. The same near-shore habitats from which an angler might expect to take largemouth bass are just as likely to produce a bowfin. A structure of some sort, around which these fish can feel secure, is the most usual place to find them, day or night.

Significance to Humans:

Like so many species and families of American freshwater fish, the bowfin has never been much sought after by humans and has remained relegated to the back benches as both food and game. However, as the more popular sport fish species decline, voracious, aggressive, hard-fighting fish such as the bowfin may soon come into their own as an interesting alternative.

Status:

Thriving throughout its American range.

Bowfin Amia calva

All herrings are deep-bodied,

slab-sided fish with large, thin

scales, large eyes, and bony heads.

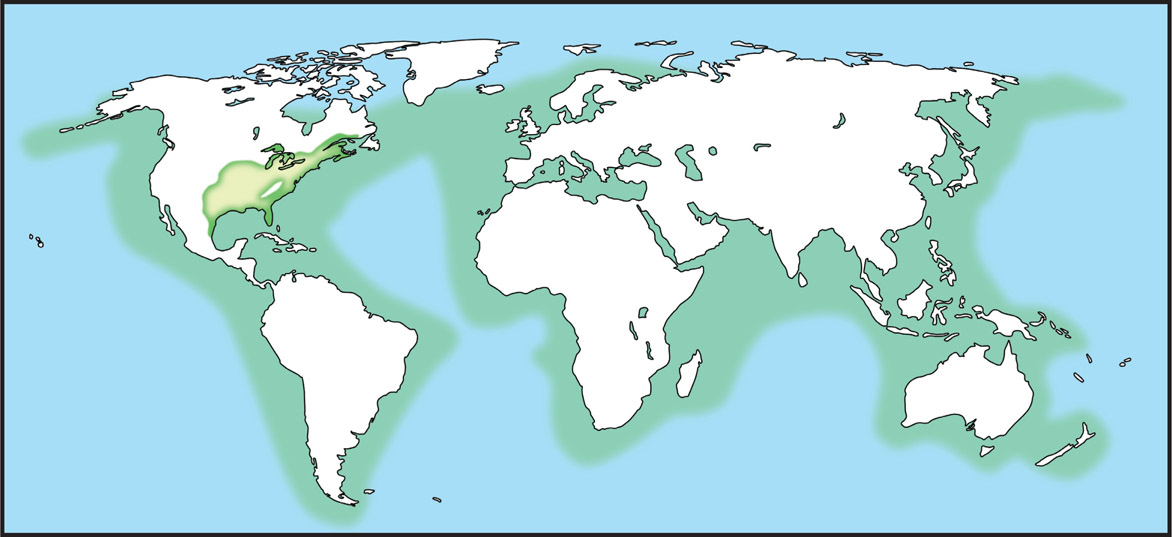

Global Range:

In saltwater, members of the herring family range throughout coastal portions of all our oceans and seas, except in the Antarctic. In freshwater, they are endemic only to the eastern and central regions of the U.S. and southern Canada.

Family Physical Traits:

All herrings are deep-bodied, slab-sided fish with large, thin scales, large eyes, and bony heads. Their bellies taper to a thin sometimes saw-like edge. Lateral lines are absent. Herrings fins have no spines and consist of a single, nearly square dorsal, a deeply forked caudal, a single long-based anal, small paired pelvics, and paired pectorals set well down on the body.

Family Diet:

The herrings are primarily plankton feeders, with the larger species adding fish to their diet.

Significance to Humans:

As a human food source, the herrings have been and continue to be one of the most important. Although less important as game fish, partly because of their dietary preferences, American and hickory shad nevertheless continue to attract a devoted group of sportfishing devotees.

Status:

Maintaining, but subject to wide fluctuations in regional populations. Herrings are a large and integral part of the planets eco-system.

Hickory Shad

Alosa mediocris

Local Names: Shad, Hick, Taylor shad

Distinguishing Field Marks:

- Typical of members of this family, the hickory shad has a deep slab-sided slivery body with large, thin scales and large eyes.

- Behind the gill covers is a dark spot followed toward the tail by a series of lighter spots.

- The single soft-rayed dorsal fin originates slightly ahead of the center of the back. There is no adipose fin. The caudal (tail) fin is deeply forked with upper and lower lobes of equal length.

- On the mid-line of the belly is a row of saw-like bony schutes.

- The mouth is terminal, with the lower jaw (unlike in the American shad) protruding beyond the upper (this characteristic is diagnostic).

Average Size:

15 to 17 inches (38 to 43 cm)

1 to 2 pounds (.45 to .90 kg)

Biology:

Hickory shad, are anadromous, spawned in freshwater, migrating to saltwater to feed and grow, then returning to freshwater to spawn. They enter river systems when the water temperature reaches the low 50 degrees F (10 C). They appear to spawn throughout the various freshwater habitats in each river system. When the river temperature has reached about 60 degrees F. (16 C), the females broadcast their ripe eggs, which are mass-fertilized by usually younger males. No nests are made and the adults abandon the fertilized eggs after spawning and begin their downstream migration back to saltwater. By mid-summer, all adults will have either died or returned to the ocean. Evidence suggests that significant numbers of hickory shad may return over several years to spawn.

Hickory shad eggs generally hatch within several days of fertilization. The newly hatched larvae drift with the current until they morph into juveniles and begin feeding on various forms of plankton suspended in the water.

In saltwater, little is known of the migratory patterns of this fish. It has been assumed that they loosely follow those of the American shad.

Diet:

As stated above, young hickory shad are plankton feeders. As they mature, their diet consists of a broader range of small foods, including insect larvae and crustaceans. As adults their diet is made up of saltwater crustaceans, small crabs, small fish, and squid.