Foreword

John Lahr

Elia Kazan was the first auteur of the American theatre: the first director to insist on having control of the entire production, the first to be billed above the title, the first to succeed both on Broadway and in Hollywood. A good director is part visionary, part showman, part critic, part father: Kazan was all these things, and more. In 1959, after the first rehearsal of Sweet Bird of Youth, Tennessee Williams wrote to Kazan, Some day you will know how much I value the great things you did with my work, how you lifted it above its measure by your great gift. I have been disloyal to nearly all lovers and friends but not to the one or two who brought my work to life. Believe me. I think I admire and value you more than anyone I have known in this profession. Kazan was the best actor's director I've worked for, Marlon Brando, himself the greatest actor of his era, said. He added, [He] got into a part with me and virtually acted it with me He was an arch manipulator of actors' feelings, and he was extraordinarily talented: perhaps we will never see his like again.

We will certainly never again see so unique a career. Kazan seemed to be part of most of the major theatrical turning points of his time. In 1932, as a stage manager and aspiring actor, he began his theatrical life with the Group Theatre; as a sidekick of both Harold Clurman and Clifford Odets, he was part of the ruling elite who reconstituted the Group Theatre during its most influential years, between 1937 and 1940. For a while, along with some other unemployed Group Theatre folk, he lived in the director Lee Strasberg's railroad flatnicknamed the Groupstroiwhere Odets, working in a closet kitchen so small that he had to rest his typewriter on his lap, wrote his groundbreaking play Awake and Sing! (1935). (Kazan stage-managed the play, which was Clurman's directing debut.) In Waiting for Lefty, Odets's polemical agitprop'salvo, which defined the voice of protest among thirties' youth, it was Kazan, a middle-class cum laude graduate of Williams College and Yale Drama School, who shouted the plays rousing final lines: Strike! Strike!! Strike!!! The press dubbed him the Proletariat Thunderbolt, and he took to wearing a working-class cloth cap with a rabbits foot pinned under the brim. Luck was certainly with him.

In his eight years as a professional actor, Kazan appeared in Odets's biggest Group Theatre hit, Golden Boy, and his biggest flop, Night Music, the last production before the Group Theatre disbanded, in 1940. As a stage director, he made Broadway hits of the three most influential midcentury American plays: Thornton Wilder's The Skin of Our Teeth, Tennessee Williams's A Streetcar Named Desire, and Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman. As a film director, he brought the Group Theatre's emphasis on psychological realism to the screen, playing midwife to many iconic performances, including James Dean's in East of Eden, Andy Griffith's in A Face in the Crowd, and Brando's in A Streetcar Named Desire and On the Waterfront. In 1948, Kazan conceived the idea of the Actors Studiohe was also part of the triumvirate who ran ita Stanislavsky-inspired school whose techniques brought new, far-reaching depth and nuance to performance. For his films, Kazan drew from a pool of Actors Studio alumni: Brando, Lee Remick, Jo Van Fleet, Geraldine Page, Karl Malden, Julie Harris, Eli Wallach, Eva Marie Saint, Carroll Baker, and Robert De Niro. Later, in 1963, when the idea of a national repertory theatre was mooted at Lincoln Center, Kazan was chosen, along with the producer Robert Whitehead, to be its first artistic director. The theatre's debut production was Arthur Miller's After the Fall (1964), a play that explored the debacle of Miller's marriage to Marilyn Monroe. Kazan was not only the play's director, he was also the man who, in 1951, had introduced Monroe to Miller.

Kazan's rise to directorial preeminence coincided with a crucial psychic shift in American culture. Between 1945 and 1955, the per capita American income nearly tripled, the greatest increase in individual wealth in the history of Western civilization. Having endured a decade of Depression, then a world war, Americans, who had postponed their desires, were now in a hurry to fulfill them. The hegemony of America's political and economic power was also played out on an individual level. The kingdom of self, not society, became the nation's obsession. Public discourse shifted from the external to the internal: from social realism to abstract expressionism; from stage naturalism to Williams's personal lyricism, from Marxism to Freudianism. This mutation in the collective imagination suited Kazan's particular directorial skill set, which understood about the subconscious and the power of the subtext. For Kazan, the greatest show on earth was the show of human emotions. In his actors and in the stories he told, Kazan's particular gift was to highlight and to release the interior drama of conflicting desires. Kazan's great contribution was to discover a theatrical vocabulary that turned psychology into behavior. My work would be to turn the inner events of the psyche into a choreography of external life, he said. He brought a new dynamism to the winded, baggy American theatre.

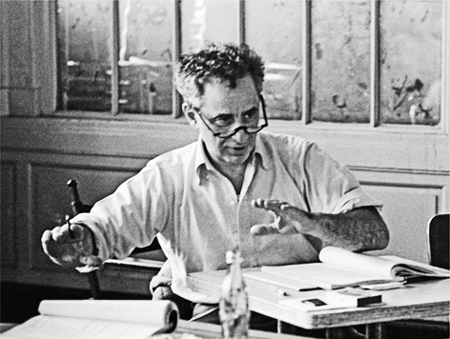

What books and photographs don't convey about Kazan is the force of his presence. Even in old age, he had a thrust and a focus that were palpable. He was small, compact, virile; it was easy to understand his talent for insinuation. He looked at you with avid eyes; he made a powerful connection. Although he spent his last years more or less housebound on the top floor of his Manhattan townhousehe died in 2003, at the age of ninety-fourKazan lived most of his life with the devil's energy, as Miller called it.

Kazan, who walked on the balls of his feet, projected himself through the world with the outcast's desire for revenge. From 1926, when he entered the WASP enclave of Williams College, his own position in American society was clear to him. I remember thinking, what the hell is wrong with me, anyway? Kazan said, who referred to himself then as a nigger. I knew what I was. An outsider. An Anatolian, not an American Every time I saw privilege from then on, I wanted to tear it down or to possess it. For his entire life, Kazan was a creature of envy; fame was the only defense against his sense of humiliation. As an actor, he carried his chippie swagger onstage. Fuck you all, big and small! I used to mutter onstage during those yearsto myself, of course, secretly, he wrote in his autobiography.

Kazan's particular appetite for vindictive triumphhis compulsive ambition and his habitual, unrepentant womanizing, which was another aspect of itstems, in part, from one inescapable childhood wound: he was not handsome. Don't you look in the mirror? his father, George, a first-generation Anatolian Greek carpet salesman, said when Kazan announced that he was going to acting school. Kazan's gnarly mug, with its large jagged nose, telegraphed both his foreignness and his ferocity. It made Kazan credible in the edgy tough-guy roles, such as Kewpie (in