VIKING

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

USA | Canada | UK | Ireland | Australia | New Zealand | India | South Africa | China

penguin.com

A Penguin Random House Company

First published by Viking Penguin, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, 2014

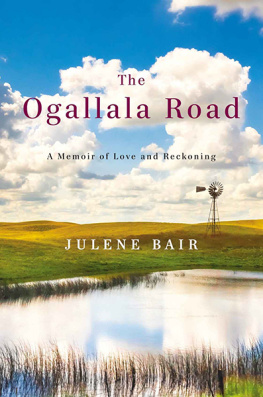

Copyright 2014 by Julene Bair

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Bair, Julene, author.

The Ogallala road : a memoir of love and reckoning / Julene Bair.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-101-60931-6

1. AgricultureEnvironmental aspectsKansas. 2. Family farmsKansas. 3. Farm lifeKansas. 4. KansasSocial life and customs. 5. Bair, JuleneHomes and hauntsKansas. 6. Agricultural conservationKansas. 7. Ogallala Aquifer. I. Title.

S589.757.K2B35 2014

636.0109781dc23

2013036969

Penguin is committed to publishing works of quality and integrity. In that spirit, we are proud to offer this book to our readers; however, the story, the experiences, and the words are the authors alone.

Version_1

FOR

Jake, Abby, Josh, Indy,

Jessamin, Jovanni, and Avery

C ONTENTS

The highest good is like water. Water gives life to the ten thousand things and does not strive. LAO TZU, Tao Te Ching

I

A R ARE F IND

Falling in love is like reading a novel, its an act of imagination, a suspension of disbelief. MARY ALLEN, Rooms of Heaven

T HESE WERE CALLED THE H IGH P LAINS BECAUSE THEY WERE FOUR THOUSAND FEET ABOVE SEA LEVEL. I could feel the altitude in the way the sun sheeted my skin. It was like standing too close to a fire with no means of escaping, unless I dashed back to the car and switched on the air conditioner. Instead, I trudged through wheat stubble that used to be the south end of our pasture, my shoes filling with powdery dirt and my socks with stickers.

This western Kansas land had belonged to the Carlsons, my mothers side of the family. When I was sixteen, my parents traded their share in it for land elsewhere in the county. Like many other successful farmers, they built a new house in town. More than three decades had passed since then. Although I knew there wouldnt be water in the creek here, I wanted to walk down its dry bed as I had in childhood, picking up every shiny piece of agate I saw, hoping to discover an arrowhead.

In the dry places, men begin to dream , wrote Wright Morris, who grew up north of here, in Nebraska. Where rivers run sand, something in man begins to flow . I thought I knew exactly what he meant. The sandy beds of dry creeks unfurl evocatively into the beckoning distance, inscribing their faint script over the land. They entice the exploring spirit.

But when I arrived at the Little Beaver, I discovered that the creek was now nothing more than a depression. Runoff from all the newly farmed pastureland had filled it with silt. Weeds grew where there had once been smooth sand, vacant and pinkish tan. In my childhood, the sand had poured sensuously through my hands, each granule having its own color, shape, size, sheen.

Our sense of beauty is a survival instinct, telling us that a place can sustain us for generations to come. Id always known this in my bones, but it wasnt until many years after I left Kansas and discovered my passion for wilderness that the intuition became conscious. This creek was now ugly. That didnt bode well for the underlying aquifers ability to support life in the future. Rain and snowmelt couldnt filter into the ground as efficiently through dirt as it could through sand. And sandy creek bottoms were critical to the meager half inch of recharge that the aquifer received each year. It needed all it could get because irrigation farmers were allowed to pump forty times that amount.

At least the north end of the pasture remained in grass. Standing here as a child, I often pretended that this was the original Kansas, pre-us. The low-growing grass stitched itself over the ground like a wooly tapestry, accented, especially in the spring, by other pastels. Blue grama grass. Apricot mallow. The yellow and cream waxen blooms of cactus and yucca. Prairie dogs chirped alarms from mounds of whitish clay, and meadowlarks sang from their perches on yucca spires, their notes climbing and dipping like winding ribbons. Instead of cows, I imagined buffalo grazing the hills. The grass had been named after the buffalo because millions of them once thrived on it.

Wed called this our canyon pasture because the creek had carved some cliffs into the otherwise smooth terrain. The canyon was really no more than an interruption in the earth, as my mother called it. But it was the wildest topography in this part of the county.

The one-room school that shed attendedand that my brothers and I also went to, before the farm schools were closed and we started riding the bus to townused to hold field trips here. The boys would try to throw rocks across the canyon, and in its shadowy ruts and ravines, we caught orange-speckled lizards as they dashed beneath the bayonet-shaped leaves of yucca. I remembered my brother Clarks hand on my arm, cautioning me to look closely before grabbing. Once, we heard a buzzing sound and jumped back from the bush Id been about to reach beneath. A tongue-flicking, tail-rattling snake lay coiled at our feet. Its vibrant, diamond-shaped head bobbed in the air, mouth open, fangs bared.

Why is it wiggling its tongue at us? I asked.

Thats how it smells you, said Bruce. Also my elder, but closer to my age than Clark, he loved nothing more than goading me.

It cant strike this far though, Clark said. Were safe.

The Little Beaver made a horseshoe turn here. Our old windmill stood on the spit of land formed by the bend. When I paid visits to the canyon as a child, my fathers ewes and their lambs would be drinking out of the low troughs. They would scatter as I approached, their hooves sounding like water riffling over rock. But today only a few cattle grazed the hill above the canyon, moving in and out of the shadows of cumulus clouds.

I used to climb the windmill and sit up there for what seemed like hours, transfixed by the shadows. They might have been cast by lily pads or boats on the bottom of a lake. From that height, I could also see our big houses red roof rising above a shelterbelt of elms. But if I climbed the windmills narrow ladder today, I knew too well that I would not see our roof or even the trees.

My grandfather Carlson had built the house high on a knoll. With stately trees and a huge red barn beside it, it had been a landmark, visible for miles around. Now it was as if all evidence of our existence had been erased by the wandlike arm of the center-pivot irrigation sprinkler Id parked beside. Like all the sprinklers that circled these plains, this one was made from an eighth mile of pipe strung between steel towers. Along the pipes length, hoses hung down with spigots on the ends, spraying a uniform mist over a 130-acre circle of six-foot-tall, fully tasseled corn.

Next page