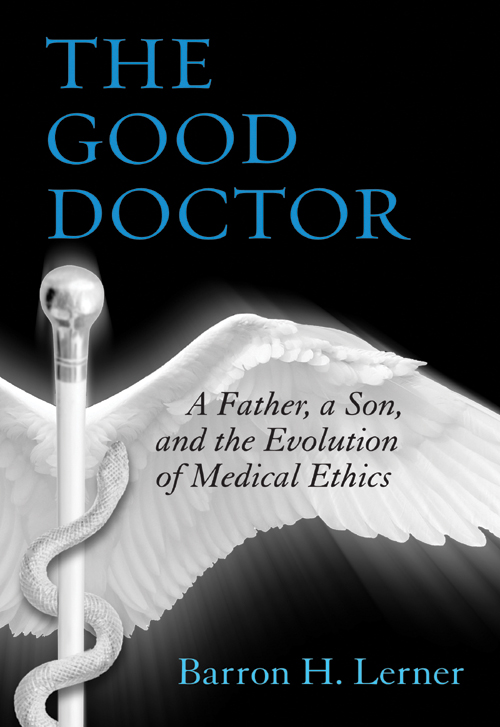

Barron H. Lerner - The Good Doctor: A Father, a Son, and the Evolution of Medical Ethics

Here you can read online Barron H. Lerner - The Good Doctor: A Father, a Son, and the Evolution of Medical Ethics full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2014, publisher: Beacon Press, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Good Doctor: A Father, a Son, and the Evolution of Medical Ethics

- Author:

- Publisher:Beacon Press

- Genre:

- Year:2014

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

The Good Doctor: A Father, a Son, and the Evolution of Medical Ethics: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Good Doctor: A Father, a Son, and the Evolution of Medical Ethics" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

As a practicing physician and longtime member of his hospitals ethics committee, Dr. Barron Lerner thought he had heard it all. But in the mid-1990s, his father, an infectious diseases physician, told him a stunning story: he had physically placed his body over an end-stage patient who had stopped breathing, preventing his colleagues from performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation, even though CPR was the ethically and legally accepted thing to do. Over the next few years, the senior Dr. Lerner tried to speed the deaths of his seriously ill mother and mother-in-law to spare them further suffering.

These stories angered and alarmed the younger Dr. Lerneran internist, historian of medicine, and bioethicistwho had rejected physician-based paternalism in favor of informed consent and patient autonomy. The Good Doctor is a fascinating and moving account of how Dr. Lerner came to terms with two very different images of his father: a revered clinician, teacher, and researcher who always put his patients first, but also a physician willing to play God, opposing the very revolution in patients rights that his son was studying and teaching to his own medical students.

But the elder Dr. Lerners journals, which he had kept for decades, showed the son how the fathers outdated paternalism had grown out of a fierce devotion to patient-centered medicine, which was rapidly disappearing. And they raised questions: Are paternalistic doctors just relics, or should their expertise be used to overrule patients and families that make ill-advised choices? Does the growing use of personalized medicinein which specific interventions may be best for specific patientschange the calculus between autonomy and paternalism? And how can we best use technologies that were invented to save lives but now too often prolong death? In an era of high-technology medicine, spiraling costs, and health-care reform, these questions could not be more relevant.

As his father slowly died of Parkinsons disease, Barron Lerner faced these questions both personally and professionally. He found himself being pulled into his dads medical care, even though he had criticized his father for making medical decisions for his relatives. Did playing Godat least in some situationsactually make sense? Did doctors sometimes know best?

A timely and compelling story of one familys engagement with medicine over the last half century, The Good Doctor is an important book for those who treat illnessand those who struggle to overcome it.

Barron H. Lerner: author's other books

Who wrote The Good Doctor: A Father, a Son, and the Evolution of Medical Ethics? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.