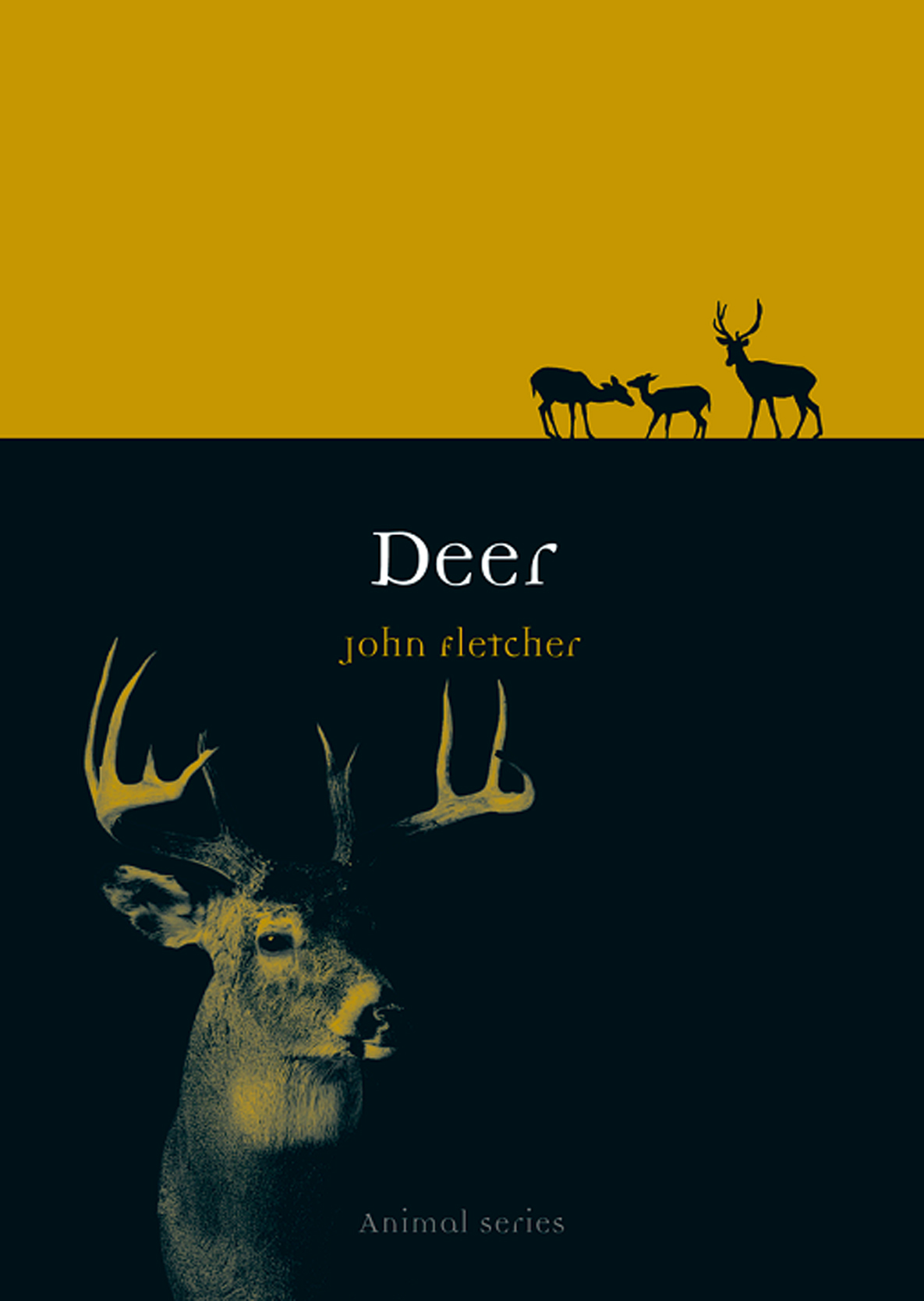

Deer

Animal

Series editor: Jonathan Burt

Already published

Ant Charlotte Sleigh Ape John Sorenson Bear Robert E. Bieder Bee Claire Preston

Camel Robert Irwin Cat Katharine M. Rogers Chicken Annie Potts Cockroach Marion Copeland

Cow Hannah Velten Crocodile Dan Wylie Crow Boria Sax Deer John Fletcher Dog Susan McHugh

Dolphin Alan Rauch Donkey Jill Bough Duck Victoria de Rijke Eel Richard Schweid

Elephant Dan Wylie Falcon Helen Macdonald Fly Steven Connor Fox Martin Wallen

Frog Charlotte Sleigh Giraffe Edgar Williams Gorilla Ted Gott and Kathryn Weir

Hare Simon Carnell Horse Elaine Walker Hyena Mikita Brottman Kangaroo John Simons

Leech Robert G. W. Kirk and Neil Pemberton Lion Deirdre Jackson Lobster Richard J. King

Monkey Desmond Morris Moose Kevin Jackson Mosquito Richard Jones Octopus Richard Schweid

Ostrich Edgar Williams Otter Daniel Allen Owl Desmond Morris Oyster Rebecca Stott

Parrot Paul Carter Peacock Christine E. Jackson Penguin Stephen Martin Pig Brett Mizelle

Pigeon Barbara Allen Rabbit Victoria Dickenson Rat Jonathan Burt Rhinoceros Kelly Enright

Salmon Peter Coates Shark Dean Crawford Snail Peter Williams Snake Drake Stutesman

Sparrow Kim Todd Spider Katja and Sergiusz Michalski Swan Peter Young Tiger Susie Green

Tortoise Peter Young Trout James Owen Vulture Thom van Dooren Whale Joe Roman

Wolf Garry Marvin

Deer

John Fletcher

REAKTION BOOKS

To Roger Short, who started me off

Published by

REAKTION BOOKS LTD

33 Great Sutton Street

London EC1V 0DX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2014

Copyright John Fletcher 2014

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in China by C&C Offset Printing Co., Ltd

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN: 9781780231242

Contents

Scythian gold stag, c. 400300 BC.

Introduction

This book is designed to appeal to both the scientifically literate as well as to those with a background in the arts. Society has never been more culturally divided between those with a scientific education and those without, and yet, ironically, there has never been a greater or more urgent need for cross-fertilization between science and the arts. Deer are ideal ambassadors to contribute, in a small way, to the breaking down of those frontiers.

Originating in the boreal regions, deer are the northern temperate grazing and browsing animals par excellence. They are supremely adapted to the seasonal availability of vegetation, as witnessed by the deciduous nature of their antlers, which are cast and regrown annually like leaves on a tree. This has made them especially fascinating not only to scientists but to myth-makers from prehistory to the present, who have used them as symbols of regeneration and longevity.

With the exception of the reindeer, until recently deer had never been domesticated. Thus, unlike the exploited and downtrodden livestock, they preserved their mystery. The domestic bovids cattle, sheep and goats with which we are more familiar, bear horns that are retained throughout the animals life. They are less seasonal, originating for the most part in the southern temperate regions of the Middle East. Eurasianss connection and even dependence on deer is much more ancient than the domestication of livestock, for in almost all cultures throughout prehistory, deer, especially, within Eurasia, red deer, were the preferred objects of the hunt.

Deer furnished antlers. The earliest sign of human life, over two million years ago, is identifiable by stone tools and for at least half a million years the antlers from deer, where available, provided our best means of knapping flints into useful shapes. In addition, by a strange symmetry, antlers provided tips for the arrows and spears with which deer were killed.

The history of humankinds adventure on this planet has been dominated thus far by the success of people from the temperate regions in making technological advances and then colonizing the rest of humanity, often brutally. In this journey deer have been our cultural companions from the snake-eating stags of Hesiod to Bambi and Rudolph.

There is now a pressing need for deer to be understood broadly, from all disciplines. As we hunt less, instead using livestock for meat, deer numbers grow. Increasingly we share their physical space as they become more suburban and mankind becomes more populous. We are compelled to make decisions that will affect them. If they become too numerous, they not only damage our forests, farms and gardens but prevent trees regenerating and destroy wild flowers and the habitats of nesting birds. Within Europe, collisions between cars and deer injure around 30,000 people annually and result in around 150 fatalities. The figures from North America are similar. The deer suffer too: almost 1 million deer are killed annually on European roads and 1.5 million in the USA. And if deer populations become too dense, suffering and mortality through starvation and disease increase. Should we stand by and allow that, or take an active role in controlling deer numbers? There are no quick fixes here. Contraception is still no panacea there are many welfare implications in administering drugs and in coping with ageing deer too.

To make intelligent decisions about the management of deer, we need to be informed both scientifically and culturally. We must examine deer from historical, biological and cultural view-points. We cannot risk these mysterious, fleetingly glimpsed, symbolically charged animals being degraded to the status of vermin or sentimentalized in a brainless anthropomorphic way. At the moment, the only feasible means of management lies in hunting, yet most Western countries are experiencing a growing shortage of hunters.

In our overwhelmingly city-based society, in which even those who live in the country are in many respects urbanized, the value of hunting is not understood. As a means of approaching and comprehending nature, of spiritual renewal, of coming closer to the animals and of taking pride in their humane treatment, hunting still has a vital role. The crosscultural approach of this book permits us to place deer in their context as a family but also to examine the place deer have held in history, largely through their crucial role as quarry in hunting.

From the prehistoric societies that moved deer to offshore islands, through the exploitation of reindeer in arctic Asia and the amazing 3,000 or more medieval deer parks in England, right up to todays 1.5 million domesticated red deer on New Zealand deer farms, this book will link mankind with deer. But it will be against a background of the evolution of the many species within the deer family, an understanding of their survival strategies, and the myth and symbolism they have inspired.