The liberation of the human mind has never been furthered by dunderheads; it has been furthered by gay fellows who heaved dead cats into sanctuaries and then went roistering down the highways of the world, proving to all men that doubt, after all, was safethat the god in the sanctuary was finite in his power, and hence a fraud. One horse-laugh is worth ten thousand syllogisms. It is not only more effective; it is also vastly more intelligent.

Prejudices, Fourth Series

Any questioning of the moral ideas that prevailthe principal business, it must be plain, of the novelist, the serious dramatist, the professed inquirer into human motives and actsis received with the utmost hostility. To attempt such an enterprise is to disturb the peaceand the disturber of the peace, in the national view, quickly passes over into the downright criminal.

A Book of Prefaces

The Life and Riotous Times of H.L. Mencken

William Manchester

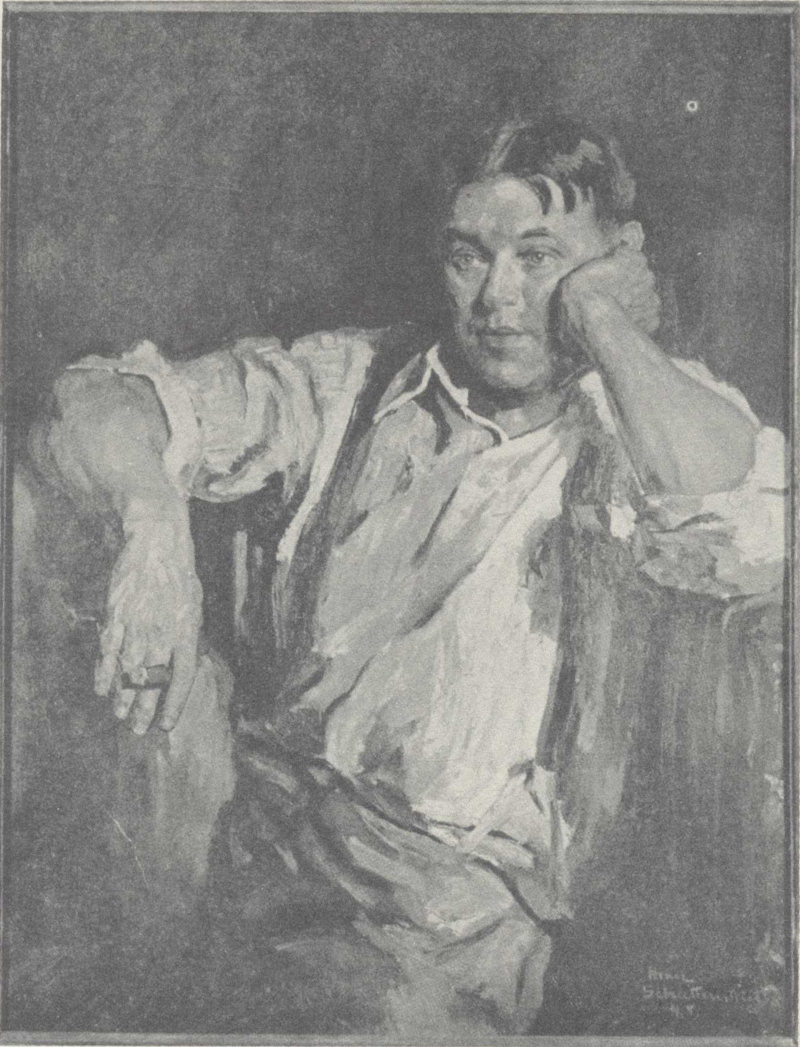

Portrait by Nikol Schattenstein

L ION OF THE T WENTIES

Copyright

The Life and Riotous Times of H.L. Mencken

Copyright 1950, 1951, 1975, 1976, 1983, 2013 by William Manchester

Cover art, special contents, and Electronic Edition 2013 by RosettaBooks LLC

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Cover jacket design by Alexia Garaventa

ISBN e-Pub edition: 9780795335648

To

Julie Manchester

with love and pride

Acknowledgments

For their help in the gathering of the information here presented, the author wishes to thank Charles Angoff, Dr. Benjamin M. Baker, Mr. and Mrs. Harry C. Black, Julian P. Boyd, Huntington Cairns, Alfred Cohn, H. Lowrey Cooling, Paul de Kruif, John Dos Passos, R. P. Harriss, Arthur Garfield Hays, Theodor Hemberger, Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Hergesheimer, Mr. and Mrs. Gerald W. Johnson, Frank R. Kent, Alfred A. Knopf, Rosalind C. Lohrfinck, Hans Marx, August Mencken, Arthur Mizener, W. Edwin Moffett, George Jean Nathan, Hamilton Owens, John W. Owens, Paul Palmer, MacLean Patterson, Paul Patterson, Burton Rascoe, Dorothy Tillett, Edmund Wilson, and William W. Woollcott.

August Mencken and George Jean Nathan must be thanked twice, each for reading the final manuscript through carefully, suggesting additions here, omissions there, and corrections everywhere.

For the subject of this book, who answered all questions, however absurd, as long as he was able; who read the early chapters and had sections from the later chapters read to him; without whose co-operation no page that follows would have been possiblefor him, mere thanks will not do. Like the A. Mitchell Palmer of his Star-Spangled Men, he should be rolled in malleable gold from head to foot, and polished until he blinds the cosmos.

Introduction to the 1986 Edition

The cooks here do a swell job with soft-shell crabs, Mencken said in a gravelly voice, peering at me over his spectacles. Beneath the old-fashioned center part of his white hair his pot-blue eyes gleamed like twin gas jets. They fry them in the altogether, he rasped. Then they add a small jock-strap of bacon.

It was June 2, 1947. We were in the dining room of the Maryland Club, the bastion of Baltimore power. The meeting was our firstI had just flown in from a Midwestern graduate school, where I was writing my dissertation on his early literary criticismand it was the beginning of a seven-year friendship, an April-December relationship which I cherished and cherish still.

This is a very high-toned club, he said over the crabs. Nothing but men. Any member who suffers a heart attack must be carried outside to the front steps before a nurse can attend him.

He was in fine form that Monday noon. At sixty-six he was still at the height of his remarkable powers and had, in fact, just completed the most productive period in his career. Since 1940 he had been feuding with Baltimores Sunpapersthe Sun, a morning paper, and the livelier Evening Sun. Disgusted with the publishers support for what he called Roosevelts War, he had refused to write for either. Instead, holed up in his study at 1524 Hollins Street, he had written his three Days books, A New Dictionary of Quotations, A Christmas Story, and two supplements to The American Language, and when we met he was at work on A Mencken Chrestomathy. His machete was still long and sharp and heavy, and he had never swung it with greater gusto.

Face-to-face with the man himself, I was enormously impressed. He had once said there would be no point in erecting a statue to him, because it would merely look like a monument for a defeated alderman. Actually he was a man of great physical presence. To be sure, his torso was ovoid, his ruddy face homely, and his legs not only stubby but also thin and bowed. Nevertheless there was a sense of dignity and purpose about all his movements, and when you were with him it was impossible to forget that you were watching a great original. Nobody else could stuff Uncle Willie stogies into a seersucker jacket with the flourish of Mencken, or wipe a blue bandanna across his brow so dramatically. His friends treasured everything about him, because the whole of the man was manifest in each of his aspectsthe tilt of his head, his close-fitting clothes, his high-crowned felt hat creased in the distinct fashion of the 1920s, his strutting walk, his abrupt gestures, his habit of holding a cigar between his thumb and forefinger like a baton, the roupy inflection of his voice, and, most of all, those extraordinary eyes: so large, and intense, and merry. He was sui generis in all ways, and the instant I saw him I wanted to write his biography.

After reading my thesis the following summer, he agreed. (I marvel at the hard work you put into it, he wrote me. It tells me many things about my own self that I didnt know myself. You will be rewarded in Heaven throughout eternity.) He did more. He agreed to read the chapters as they accumulated, with the understanding that he would note only inaccuracies, never my opinions. And then, swallowing his pride, he asked the Evening Sun to hire me as a reporter, thus enabling me to support myself while working on the book. My journalistic career in Baltimore was launched in September. Beginning that autumn I saw a great deal of Mencken, sometimes at the Sunpapers, which he now began visiting with growing frequency; other times in his club, the Enoch Pratt Free Library, Miller Brothers restaurant, on long walks through downtown Baltimore, and in his home. The high-ceilinged Hollins Street sitting room, with its cheery fireplace, dark rosewood furniture, and Victorian bric-a-brac became a kind of shrine for me. I treasured his letters and kept elaborate notes on all our meetings, which, he being Mencken, really were notable.

One warm day I covered a fire near his home. The neighborhood had turned; he and his brother were the only white men left. Thus I was surrounded by black spectators when Mencken appeared, extended his hand, and greeted me: Dr. Livingstone, I presume? He was perspiring profusely and, I thought, excessively. But then, he was hyperbolic in everything, especially language. He never asked me to join him for a beer; I was invited to hoist a schooner of malt. Anthony Comstock hadnt merely been a censor; he had been a great smeller. Mencken was forever stuffing letters to me with absurd advertisements for chiropractors, quack remedies, and evangelical tracts. Once, while showing me his manuscript collection in the Pratt Library, he said he was worried about its security; the stack containing it was locked, but he wanted a sign, too. Saying KEEP OUT ? I asked. No, he said. Saying: WARNING: TAMPERING WITH THIS GATE WILL RELEASE CHLORINE GAS UNDER 250 POUNDS PRESSURE .