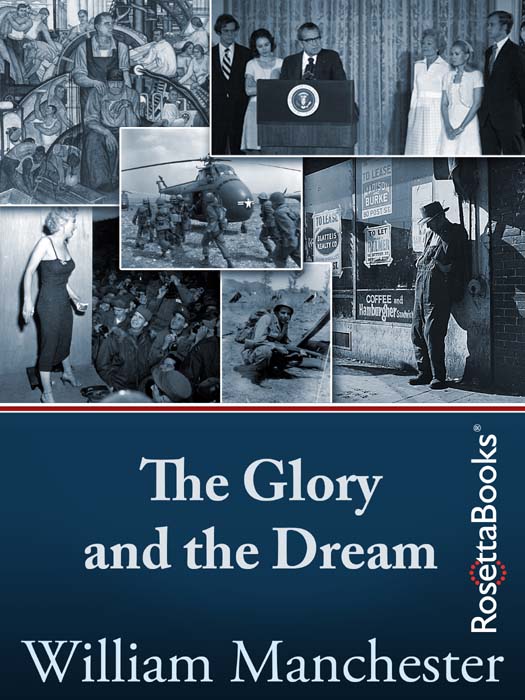

The Glory and the Dream

A Narrative History of America, 19321972

William Manchester

Copyright

The Glory and the Dream

Copyright 1973, 1974, 2013 by William Manchester

Cover art, special contents, and Electronic Edition 2013 by RosettaBooks LLC

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Cover jacket design by Alexia Garaventa

ISBN e-Pub edition: 9780795335570

To

Laurie Manchester

and to

her future

Whither is fled the visionary gleam?

Where is it now, the glory and the dream?

Wordsworth

PROLOGUE

Rock Bottom

In the desperate summer of 1932, Washington, D.C., resembled the besieged capital of an obscure European state. Since May some twenty-five thousand penniless World War veterans had been encamped with their wives and children in District parks, dumps, abandoned warehouses, and empty stores. The men drilled, sang war songs, and once, led by a Medal of Honor winner and watched by a hundred thousand silent Washingtonians, they marched up Pennsylvania Avenue bearing American flags of faded cotton. Most of the time, however, they waited and brooded. The vets had come to ask their government for relief from the Great Depression, then approaching the end of its third year; specifically, they wanted immediate payment of the soldiers bonus authorized by the Adjusted Compensation Act of 1924 but not due until 1945. If they could get cash now, the men would receive about $500 each. Headline writers had christened them the Bonus Army, the bonus marchers. They called themselves the Bonus Expeditionary Force.

BEF members had hoped in vain for congressional action. Now they appealed to President Hoover, begging him to receive a delegation of their leaders. Instead he sent word that he was too busy and then proceeded to isolate himself from the city. Presidential plans to visit the Senate were canceled; policemen patrolled the White House grounds day and night. For the first time since the Armistice, the Executive Mansion gates were chained shut. HOOVER LOCKS SELF IN WHITE HOUSE , read a New York Daily News headline. He went even further. Barricades were erected; traffic was shut down for a distance of one block on all sides of the Mansion. A one-armed veteran, bent upon picketing, tried to penetrate the screen of guards. He was soundly beaten and carried off to jail.

In retrospect this panoply appears to have been the overreaction of a frightened, frustrated administration. The bonus marchers were unarmed, had expelled radicals from their ranks, anddespite their evident hungerwerent even panhandling openly. They seemed too weak to be a menace. Drew Pearson, a thirty-four-year-old Baltimore Sun reporter, described them as ragged, weary, and apathetic, with no hope on their faces. Increasingly, the BEF vigil had become an exercise in endurance. A health department inspector described the camps sanitary conditions as extremely bad. Makeshift commissaries depended largely upon charity. Truckloads of food arrived from friends in Des Moines and Camden, New Jersey; a hundred loaves of bread were being shipped each day from one sympathetic baker; a thousand pies came from another; the Veterans of Foreign Wars sent $500, and the bonus marchers raised another $2,500 by staging boxing bouts among themselves in Griffith Stadium. It was all very haphazard. The administration was doing virtually nothingWashington police had aroused Hoovers wrath by feeding the Districts uninvited guests bread, coffee, and stew at six cents a dayand by mid-August brutal temperatures were approaching their annual height, diminishing water reserves and multiplying misery.

In those years Washington was officially classified by the British Foreign Office as a sub-tropical climate. Diplomats loathed its wilting heat and dense humidity; with the exception of a few downtown theaters which advertised themselves as refrigerated, there was no air-conditioning. In summer the capital was a city of awnings, screened porches, ice wagons, summer furniture and summer rugs, and in the words of an official guidebook it was also a peculiarly interesting place for the study of insects. Lacking shade or screens, the BEF was exposed to the full fury of the season. When the vets vanguard had entered the District, gardens were flowering in their springtime glory. By July the blossoms of magnolia and azalea were long gone, and the cherry trees were bare. Even the earth, it seemed, was pitiless. The vets had taken on the appearance of desert creatures; downtown merchants complained that the sight of so many down-at-the-heel men has a depressing effect on business. That, really, was the true extent of their threat to the country.

***

But if the BEF danger was illusion, Washingtons obscurity on the international scene in that era, and its dependency upon Europe, were more substantive. Among the sixty-five independent countries then in the world, there was but one superpower: Great Britain. The Union Jack flew serenely over one-fourth of the earths arable surfacein Europe, Asia, and Africa; North, Central, and South America; Australia, Oceania, and the West Indies. The sun literally never sank upon it. Britains Empire commanded the allegiance of 485 million people, and if you wanted to suggest stability you said solid as the Rock of Gibraltar, or safe as the Bank of England, which with the pound sterling at $4.86 seemed the ultimate in fiscal security. Air power was the dream of a few little-known pilots and a cashiered American general named Mitchell; what counted then were ships, and virtually no significant world waterway was free of Londons dominion. Gibraltar, Suez, the Gulf of Aden, the Strait of Singapore, and the Cape of Good Hope were controlled directly by the Admiralty. The Strait of Magellan was at the mercy of the British naval station in the Falkland Islands, and even the Panama Canal lay under the watchful eye of H.M.s Caribbean squadron. As a consequence of all this, the United States was shielded by the Royal Navy as surely as any crown colony. Lloyds of London offered 500-to-1 against any invasion of the U.S. And when Fortune assured its readers that the Atlantic and Pacific were still a protection and will forever remain so, no matter how fast ships may sail or airplanes may fly, the magazine was assuming that the British fleet, which had ruled the waves throughout American history, would go right on ruling them.

Washington made the same assumption; the country lacked the status, the pretensions, and most of the apparatus of a great power. The capital was a slumbering village in summer, largely forgotten the rest of the year. In size it ranked fourteenth among American cities. Most big national problems were decided in New York, where the money was; when federal action was required, Manhattans big corporation lawyersmen like Charles Evans Hughes, Henry L. Stimson, and Elihu Rootcame down to guide their Republican protgs. President Coolidge had usually finished his official day by lunchtime. Hoover created a stir by becoming the first chief executive to have a telephone on his desk. He also employed five secretariesno previous President had required more than oneand summoned them by an elaborate buzzer system.

Foggy Bottom, the site of the present State Department Building, was a Negro slum. The land now occupied by the Pentagon was an agricultural experimental station and thus typical of Washingtons outskirts; large areas close to the very heart of the nations lawmaking, the