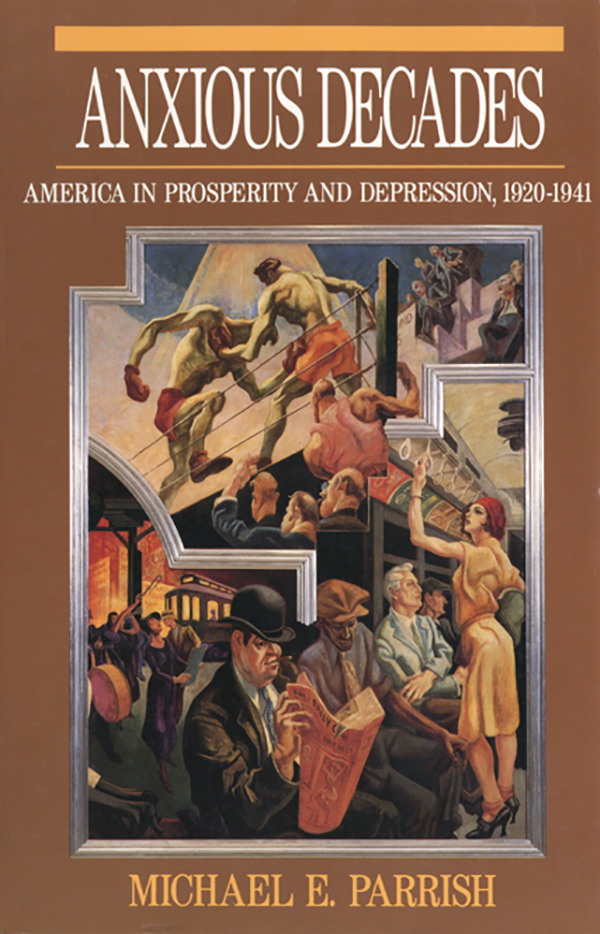

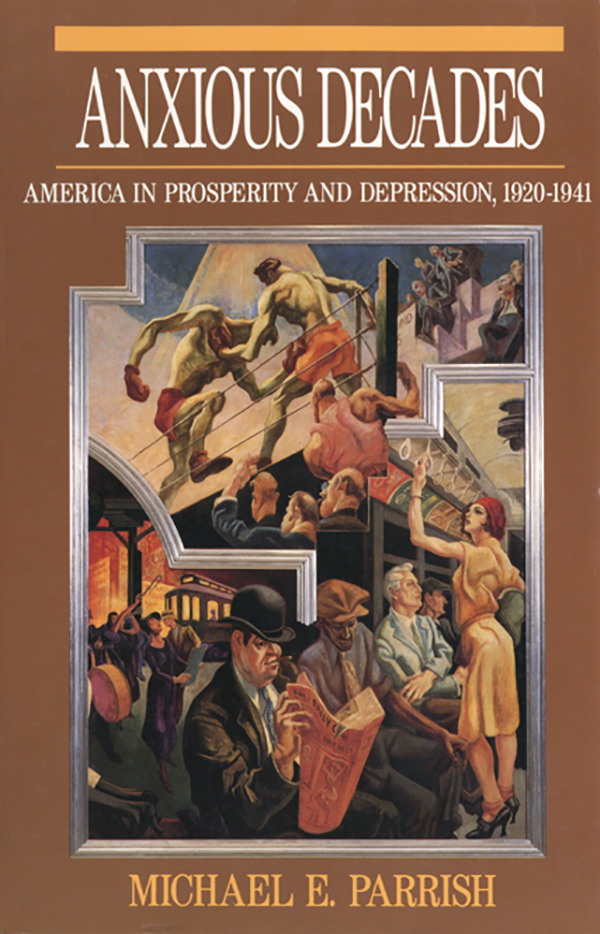

ANXIOUS DECADES

America in Prosperity and

Depression

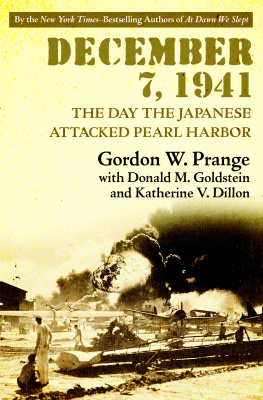

1920  1941

1941

MICHAEL E. PARRISH

W W NORTON & COMPANY NEW YORK LONDON

Anyone who writes a work of broad historical interpretation accumulates along the way a considerable intellectual debt to many people. At the threshold, I wish to thank the many scholars whose books and articles are noted all too briefly in the bibliographical comments at the end of this book. It is impossible to pay them proper tribute. But without their imagination and hard work, I could not have attempted this volume.

John Blum and Edwin Barber first suggested that I participate in the Norton series on twentieth-century America. To them I therefore owe the ensuing years of frustration and creative joy. John remains a source of both inspiration and discouragement to his former students and all who labor to make sense out of modern America. We shall never know as much as he does about these matters; and we shall never write about them with such eloquence. Ed is a peerless editor, whose skill with the pen is matched only by his patience with authors who miss deadlines and still nag him for more money.

A number of my colleagues at the University of California, San Diego, shared their rich knowledge and insight into a number of the issues discussed in this volume. I thank especially Michael Bernstein, Stephanie McCurry, Steve Hahn, and John Galbraith.

Alan Brinkley, Nelson Lichtenstein, and David Kennedy read the entire manuscript, offered valuable suggestions, and spared me from the embarrassment of many errors. This would have been a better book had I the energy and wit to incorporate all the sound advice they offered. As it stands, they are absolved from the remaining defects of interpretation and organization.

I owe special thanks to Robin Mendelson, Ted Johnson, and Amy Loyd for unstinting editorial assistance, and to Ruth Mandel for her wise choice of many photographs and cartoons.

Finally, I thank Susan, who suffered through the authors many moments of mental distraction with unfailing good cheer and encouragement.

San Diego, California

1991

On the assumption that most people who read this book will wish to deepen their general understanding of particular historical controversies and events rather than conduct independent research, I have refrained in this bibliography from listing relevant manuscript collections housed at the Library of Congress, the National Archives, and presidential libraries at West Branch, Iowa, and Hyde Park, New York. I have also not noted the many newspapers and periodicals that I consulted, such as the New York Times, the WallStreet Journal, the American Mercury, Fortune, the Ladies Home Journal, the New Republic, the Saturday Evening Post, and the Nation.

PART ONE

1. Republican Restoration

A number of works that survey the postwar decade have achieved the status of classics and should be read by any serious student of the period. These include Frederick Lewis Allens Only Yesterday: An Informal History of the 1920s (New York, 1931); Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., The Crisis of the Old Order (New York, 1957); William E. Leuchtenburg, The Perils of Prosperity, 19141932 (Chicago, 1958); John D. Hicks, Republican Ascendancy, 19211933 (New York, 1960); and Arthur S. Link, What Happened to the Progressive Movement in the 1920s? American Historical Review 64 (1959), 83351. Still useful for their insight into how historians have viewed the era are Henry F. May, Shifting Perspectives on the 1920s, Mississippi Valley Historical Review 43 (1956), 40527; and Burl Noggle, The Twenties: A New Historiographical Frontier, Journal. Of American History 53 (1966), 299314.

The best accounts of the impact of World War I upon American society and the progressive movement are David Kennedy, Over Here: The First World War and American Society (New York, 1980); and chapters 10 and 11 in John Milton Cooper, Jr., Pivotal Decades: The United States, 1900-1920 (New York, 1990). For the tragic end of the Wilson administration see Gene Smith, When the Cheering Stopped: The Last Years of Woodrow Wilson (New York, 1964). The presidential election of 1920 is detailed in Wesley M. Bagby, The Road to Normalcy: The Presidential Campaign and Election of 1920 (Baltimore, 1962).

The suppression of civil liberties during and immediately after the conflict is treated in Paul L. Murphy, World War I and the Origins of Civil Liberties (New York, 1970); Harry N. Scheiber, The Wilson Administration and Civil Liberties, 19171921 (Ithaca, N.Y., 1960); Robert K. Murray, Red Scare: A Study in National Hysteria, 19191920 (Minneapolis, 1955); Michal Belknap, The Mechanics of Repression: J. Edgar Hoover, the Bureau of Investigation and the Radicals, 19171925, Crime and Social Justice 7 (1977); and two works by Stanley Coben, A. Mitchell Palmer (New York, 1962) and A Study in Nativism: The American Red Scare of 191920, Political Science Quarterly 79 (1964), 5275.

On the racial violence of the immediate postwar period see Lee E. Williams, Anatomy of Four Race Riots: Racial Conflict in Knoxville, Elaine, Tulsa, and Chicago, 19191921 (Hattiesburg, Miss., 1972); and William M. Tuttle, Race Riot: Chicago in the Red Summer of 1919 (New York, 1970). Two of the most important labor strikes are analyzed in Robert L. Friedheim, The Seattle General Strike (Seattle, 1964); Francis Russell, A City in Terror: 1919, the Boston Police Strike (New York, 1975); and Jonathan R. White, A Triumph of Bureaucracy: The Boston Police Strike and the Ideological Origins of the American Police Structure (Ph.D. dissertation, University Microfilms, 1982).

The best biography of Warren G. Harding remains Francis Russell, The Shadow of Blooming Grove (New York, 1968), but it should be supplemented with Randolph C. Downes, The Rise of Warren Gamaliel Harding, 18651920 (Columbus, Ohio, 1970); and Charles L. Mee, The Ohio Gang: The World of Warren G. Harding (New York: 1981). Robert K. Murray has written two excellent studies of the administrations overall approach to public policy: The Harding Era: Warren G. Harding and His Administration (Minneapolis, 1969) and The Politics of Normalcy: Governmental Theory and Practice in the Harding-Collidge Era (New York, 1973). A useful perspective is also provided by Eugene P. Trani and David L. Wilson, The Presidency of Warren G. Harding (Lawrence, Kan., 1977). For the Teapot Dome affair, two scholars have separated fact from fiction: J. Leonard Bates, The Origins of Teapot Dome: Progressives, Parties, and Petroleum, 19091921 (Urbana, Ill., 1963); and Burl Noggle, Teapot Dome: Oil and Politics in the 1920s (Baton Rouge, 1962).

On leading figures in Hardings administration see especially Betty Glad, Charles Evans Hughes and the Illusion of Innocence: A Study in American Diplomacy (Urbana, Ill., 1966); Donald Winters, Henry Cantwell Wallace (Urbana, Ill., 1970); Harvey OConnor, Mellons Millions: The Biography of a Fortune (New York, 1933); Ellis W. Hawley, ed., Herbert Hoover as Secretary of Commerce, 19211928: Studies in New Era Thought and Practice (Iowa City, 1981); and Gary D. Best, The Politics of American Individualism: Herbert Hoover in Transition, 19181921

Next page

1941

1941