the dark side

of innocence

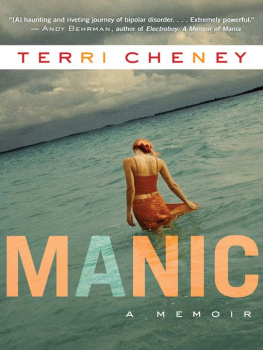

Also by Terri Cheney

Manic: A Memoir

ATRIA BOOKS

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

To the best of my ability, I have re-created events, locales, people, and

organizations from my memories of them. In order to maintain the anonymity

of others, in some instances I have changed the names of individuals and

places, and the details of events. I have also changed some identifying

characteristics, such as physical descriptions, occupations, and places of

residence.

Copyright 2011 by Terri Cheney

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book

or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information,

address Atria Books Subsidiary Rights Department,

1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Atria Books hardcover edition March 2011

ATRIA BOOKS and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your

live event. For more information or to book an event, contact the

Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our

website at www.simonspeakers.com .

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 978-1-4391-7621-4

ISBN 978-1-4391-7625-2 (ebook)

To my mother

the dark side

of innocence

Introduction

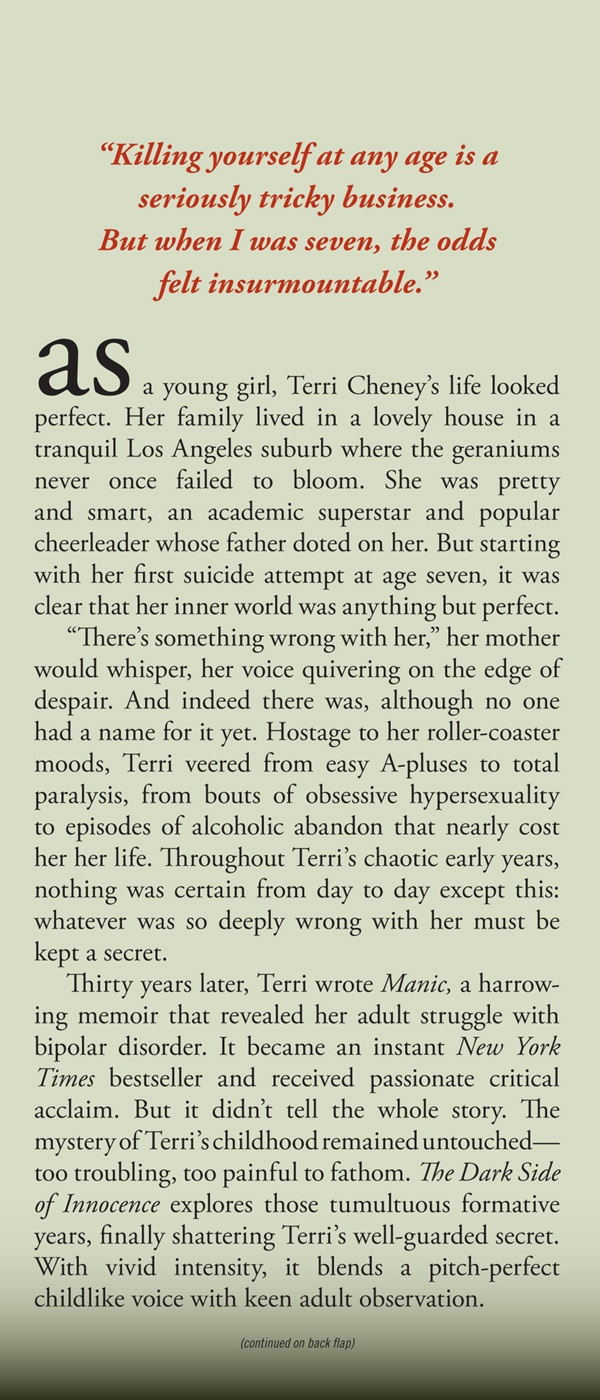

Theres a beast out there, and its preying on children. I didnt know this when I was growing up. I only knew that there was something very, very wrong with me. It wasnt until 1994, when I was thirty-four years old, that I finally found the right name for it: bipolar disorder.

After years of secretly struggling with the disease, I wrote a book about my experience. Manic: A Memoir was published in 2008. It describes my life as a Beverly Hills entertainment attorneyoutwardly successful, representing the likes of Michael Jackson, Quincy Jones, and major motion picture studios. But behind the carefully poised faade was a string of bloody suicide attempts, nights in jail, repeated hospitalizations, and ruined relationships. When I was depressed, I was completely paralyzed, literally hiding out under my desk. But when I was manic, I made up for the lost time with dazzling productivity, charisma, and boundless energy.

I told no one about my illness back thennot my friends, my family, my coworkers; no one except my doctors. With the publication of Manic, of course, the whole world was going to be privy to my secret. I rationalized this by telling myself that no one was really going to care. Who could possibly be interested in my messy, chaotic blur of a life?

I was wrong.

To my everlasting surprise, Manic hit the New York Times best-seller list a month after its release. As of this writing, it is in its tenth printing, has been translated into eight foreign languages, and was even optioned by HBO for a television series, the ultimate stamp of pop culture approval. Dont misunderstand me: I love my book, I think its a very good book, and I worked seven long years on it. But I also know that its success has little to do with my writing. The time has finally come for awareness: the world seems to have a rampant curiosity about bipolar disorder. Almost without exception, everyone Ive talked to either knows or knows of someone with this disease (or has it themselves).

I was completely unprepared for the torrent of emails I received: the outpouring of gratitude, the baring of souls. But what moved me the most, what I kept coming back to over and over again, were the emails from parents of bipolar children. They were heartrending, passionate, and unapologetically hungry for information. Why were their children acting like this? Did I understand the symptoms? Did I know of a cure? The love was palpable, as was the desperation.

In many of these emails, and in the numerous interviews, readings, and lectures Ive given since, the same question kept popping up, without fail: How old was I when I realized that something was seriously wrong with me? I remember the first time I answered this question. It was during a live radio show, and I was nervous. My mind flashed immediately to a prolonged bout of depression I suffered when I was sixteen years old. Sixteen, I quickly replied. New authors get a little glib with repetition, and sixteen soon became my stock answer. But deep down, I knew that wasnt right. My early childhood wasnt just a strange one; it was a sick one, and there was more to the story than I was willing to tell.

Then in May of 08, shortly after my book came out, I visited New York City for a reading. I was in a downtown subway station when I spotted a bright red Newsweek banner and, in bold type, the cover story: Growing Up Bipolar. I devoured that article. I was shocked to learn that at least eight hundred thousand children in the United States have been diagnosed as bipolar. (Ive since seen estimates of over a million.) I would later learn from a New York Times Magazine cover article that there has been a fortyfold increase in the diagnosis in recent yearsa whopping 4,000 percent increase since the mid-1990s, according to National Public Radio.

The very next day, I was sitting in my editors office, discussing what to write next. My editor looks like a Pre-Raphaelite angel, which is disconcerting enough. But then out of the blue, just like that, she said, What about your childhood?

I froze. What about it?

Lots of people seem curious. You dont mention it much in Manic, you know.

Theres a very good reason for that: I wanted people to buy the book. Difficult as it was for me to imagine anyone caring about the exploits of my bipolar adulthood, I found it even harder to conceive of anyone being interested in my morass of a childhood. At least when I was an adult, I had a name for what was wrong with me: manic depression. Its easier to make sense of thingseven very disturbing things like sexual acting out and suicidalitywhen theres a big, fat label slapped on top. But as a child, I knew nothing. I had no diagnosis. All I had was a vague and gnawing awareness that I was different from other children, and that different was not good. Different must be kept hidden.

I dont think I can remember back that far, I said, glancing away from Sarahs eyes to the concrete block of a building across the way.

It was part evasion, part truth. Memory has always been a tricky business with me, especially since the twelve rounds of electroshock therapy I went through in 1994. I write what I remember as honestly and accurately as I can. But Im never quite sure that what I remember is what other people see as true. Mental illness has its own lens.

Thats exactly what you said about Manic, and yet you managed. Sarah paused, and the silence drew me back in to her. I think you should try.

I left her office that afternoon convinced that I would send a polite but discouraging email in a couple of days. But she got me thinking, which is what a good editor is supposed to do. And thinking. And eventually, jotting down glimpses of the past. I pored over what mementos I still have of my childhood: some photos, early writings, a cherished keepsake or two. I plagued my mother and brother with questions (my father, unfortunately, died in 1997): Did this really happen? Did I really do that? Fragments gradually became paragraphs, images evolved into scenes. Once I started to remember, windows that I thought were welded shut flew open. I may not have recalled the exact dialogue spoken at the dinner table, but I couldnt forget the feelings. I was seven years old all over again, and frankly, it was terrifying.

Next page