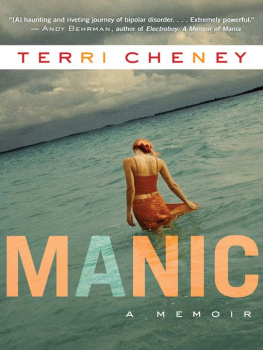

Terri Cheney

Manic

A Memoir

To my mother and father

Contents

I didnt tell anyone that I was going to Santa

I was a star in the makingcold and chilly, with

I was sitting in the head and neck surgeons sleek

I have never sinned on purpose. Not that it mattered

I knew I was getting a little bit manic when

The room was a cheery one, as institutions go: daisies

We were the Gatsby couple, or so our friends called

Its a little-known secret, and it should probably stay that

I woke up strapped to a bed, covered in a

I met the doctor of my dreams at my fathers

I hadnt planned on being manic. For months, Id looked

Ive never liked the telephone. Its a noisy, shrill intruder.

My sins are greatest against those I never wished to

Id never hit a man before. I was surprised how

Its impossible, in my opinion, to have a normal relationship

I look harmless enough, I suppose. Sitting here on this

A lady doesnt scratch, my mother used to warn me,

The valet sprang into action the second my car pulled

Im sitting in my favorite caf, writing a line, crossing

If you come with me on this journey, I think a word of warning is in order: manic depression is not a safe ride. It doesnt go from point A to point B in a familiar, friendly pattern. Its chaotic, unpredictable. You never know where youre heading next. I wanted this book to mirror the disease, to give the reader a visceral experience. Thats why Ive chosen to tell my life story episodically, rather than in any chronological order. Its truer to the way I think. When I look back, I rarely remember events in terms of date or sequence. Rather, I remember what emotional state I was in. Manic? Depressed? Suicidal? Euphoric? Life for me is defined not by time, but by mood.

Ive tried to stay as true as I can to what I remember. But mental illness creates its own vibrant reality, which is so convincing its sometimes hard to figure out exactly what is real and what is not. It gets even harder as time goes by, because memory is the first casualty of manic depression. When Im manic, all I remember is the moment. When Im depressed, all I remember is the pain. The surrounding details are lost on me.

But the illness, ironically, has impaired me far less than the treatment. Ive long since lost track of all the psychotropic medications Ive had to take over the years, or the nature and number of their side effects. More devastating, however, was the course of electroshock therapy (ECT) I went through in 1994. ECT can be of great help as a last-resort treatment, but its notorious for wiping out memory. For a while, I forgot even the simplest things: what part of town I lived in, my mothers maiden name, what scissors were for. Some of this was eventually restored, but I still have trouble recalling past events and retaining the memories of new ones. The world has never seemed as sharp and clear as it did before the ECT.

In some cases, the events I describe can be documented by police or hospital records (although some of the hospitals no longer exist). Ive elected to change the names of most of the people and institutions depicted, to protect their identities. The experiences Ive written about are often difficult and private, and I prefer just to tell my own story.

Telling my story is whats kept me alive, even when death was at its most seductive. Thats why Ive chosen to share my personal history, although some of it is still painful to recall even through a haze of medication, mental illness, and electroshock therapy. But the disease thrives on shame, and shame thrives on silence, and Ive been silent long enough. This book represents what I remember. This book is my truth.

Terri Cheney

Los Angeles, California

I didnt tell anyone that I was going to Santa Fe to kill myself. I figured that was more information than people needed, plus it might interfere with my travel plans if anyone found out the truth. People always mean well, but they dont understand that when youre seriously depressed, suicidal ideation can be the only thing that keeps you alive. Just knowing theres an outeven if its bloody, even if its permanentmakes the pain almost bearable for one more day.

Five months had passed since my fathers death from lung cancer, and the world was not a fit place to live in. As long as Daddy was still alive, it made sense to get up every morning, depressed or not. There was a war on. But the day I gave the order to titrate his morphine to a lethal dose, the fight lost all meaning for me.

So I wanted to die. I saw nothing odd about this desire, even though I was only thirty-eight years old. It seemed like a perfectly natural response, under the circumstances. I was bone-tired, terminally weary, and death sounded like a vacation to me, a holiday. A somewhere else, which is all I really wanted.

When I was offered the chance to leave L.A. to take an extended trip by myself to Santa Fe, I was ecstatic. I leased a charming little hacienda just off Canyon Road, the artsiest part of town, bursting with galleries, jazz clubs, and eccentric, cat-ridden bookstore/cafs. It was a good place to live, especially in December, when the snow fell thick and deep on the cobblestones, muffling the street noise so thoroughly that the city seemed to dance its own soft-shoe.

There was an exceptional amount of snowfall that particular December. Everything seemed a study in contrast: the fierce round desert sun, blazing while I shivered; blue-white snow shadows against thick red adobe walls; and always, everywhere I looked, the sagging spine of the old city pressing up against the sleek curves of the new. But the most striking contrast by far was me: thrilled to tears simply to be alive in such surroundings, and determined as ever to die.

I never felt so bipolar in my life.

The mania came at me in four-day spurts. Four days of not eating, not sleeping, barely sitting in one place for more than a few minutes at a time. Four days of constant shoppingand Canyon Road is all about commerce, however artsy its facade. And four days of indiscriminate, nonstop talking: first to everyone I knew on the West Coast, then to anyone still awake on the East Coast, then to Santa Fe itself, whoever would listen. The truth was, I didnt just need to talk. I was afraid to be alone. There were things hovering in the air around me that didnt want to be remembered: the expression on my fathers face when I told him it was stage IV cancer, already metastasized; the bewildered look in his eyes when I couldnt take away the pain; and the way those eyes kept watching me at the end, trailing my every move, fixed on me, begging for the comfort I wasnt able to give. I never thought I could be haunted by anything so familiar, so beloved, as my fathers eyes.

Mostly, however, I talked to men. Canyon Road has a number of extremely lively, extremely friendly bars and clubs, all of which were within walking distance of my hacienda. It wasnt hard for a redhead with a ready smile and a feverish glow in her eyes to strike up a conversation and then continue that conversation well into the early-morning hours, at his place or mine. The only word I couldnt seem to say was no. I ease my conscience by reminding myself that manic sex isnt really intercourse. Its discourse, just another way to ease the insatiable need for contact and communication. In place of words, I simply spoke with my skin.

I had long since decided that Christmas Eve would be my last day on this earth. I chose Christmas Eve precisely because it had meaning and beautynowhere more so than in Santa Fe, with its enchanting festival of the farolitos . Every Christmas Eve, carolers come from all over the world to stroll the lantern-lit streets until dawn. All doors are open to them, and the air is pungent with the smell of warm cider and pion.

Next page