In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at permissionshbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

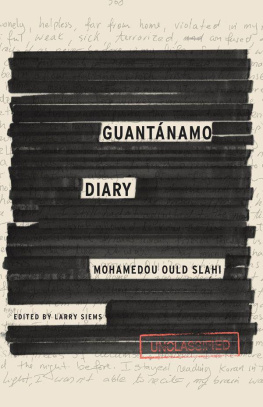

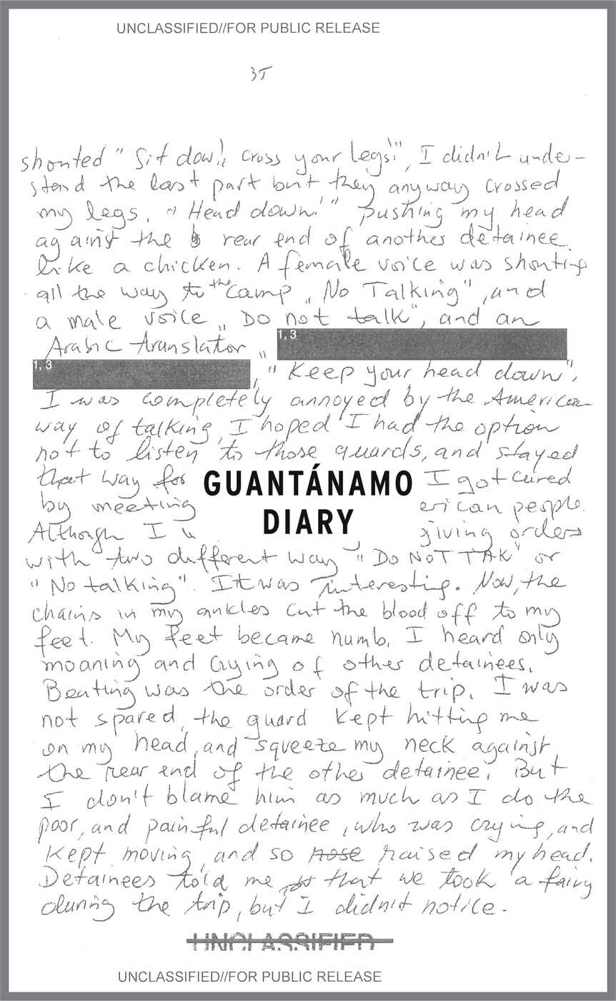

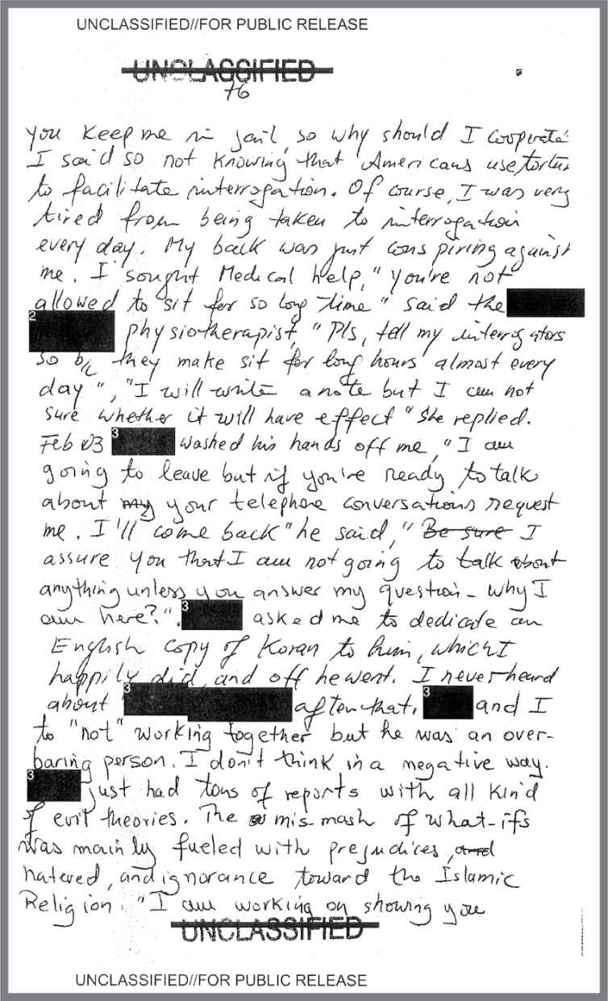

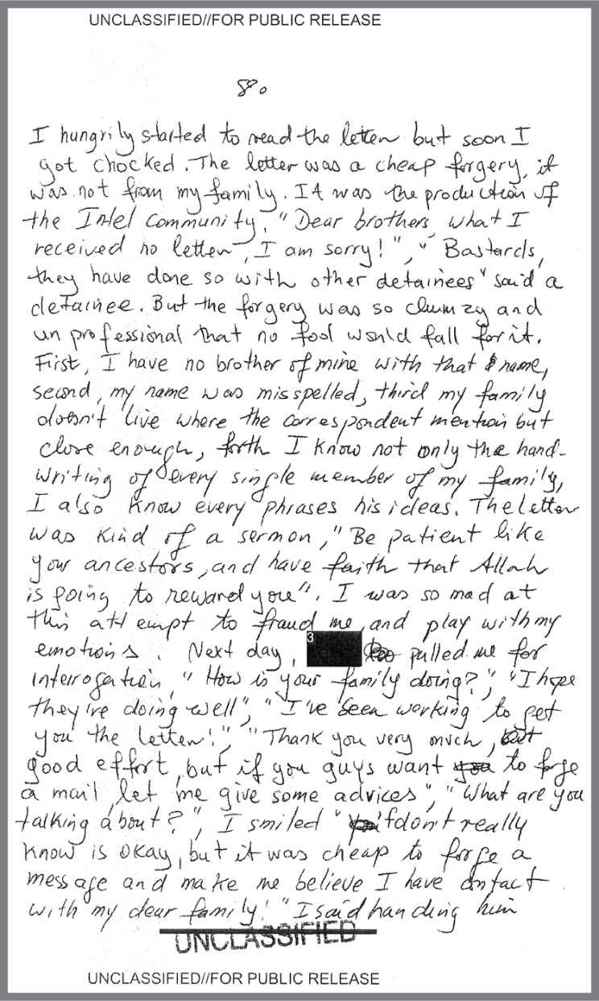

This book is an edited version of the 466-page manuscript Mohamedou Ould Slahi wrote by hand in his Guantnamo prison cell in the summer and fall of 2005. It has been edited twice: first by the United States government, which added more than 2,500 black-bar redactions censoring Mohamedous text, and then by me. Mohamedou was not able to participate in, or respond to, either one of these edits.

He has, however, always hoped that his manuscript would reach the reading publicit is addressed directly to us, and to American readers in particularand he has explicitly authorized this publication in its edited form, with the understanding and expressed wish that the editorial process be carried out in a way that faithfully conveys the content and fulfills the promise of the original. He entrusted me to do this work, and that is what I have tried to do in preparing this manuscript for print.

Mohamedou Ould Slahi wrote his memoir in English, his fourth language and a language he acquired largely in U.S. custody, as he describes, often amusingly, throughout the book. This is both a significant act and a remarkable achievement in itself. It is also a choice that creates or contributes to some of the works most important literary effects. By my count, he deploys a vocabulary of under seven thousand wordsa lexicon about the size of the one that powers the Homeric epics. He does so in ways that sometimes echo those epics, as when he repeats formulaic phrases for recurrent phenomena and events. And he does so, like the creators of the epics, in ways that manage to deliver an enormous range of action and emotion. In the editing process, I have tried above all to preserve this feel and honor this accomplishment.

At the same time, the manuscript that Mohamedou managed to compose in his cell in 2005 is an incomplete and at times fragmentary draft. In some sections the prose feels more polished, and in some the handwriting looks smaller and more precise, both suggesting possible previous drafts; elsewhere the writing has more of a first-draft sprawl and urgency. There are significant variations in narrative approach, with less linear storytelling in the sections recounting the most recent eventsas one would expect, given the intensity of the events and proximity of the characters he is describing. Even the overall shape of the work is unresolved, with a series of flashbacks to events that precede the central narrative appended at the end.

In approaching these challenges, like every editor seeking to satisfy every authors expectation that mistakes and distractions will be minimized and voice and vision sharpened, I have edited the manuscript on two levels. Line by line, this has mostly meant regularizing verb tenses, word order, and a few awkward locutions, and occasionally, for claritys sake, consolidating or reordering text. I have also incorporated the appended flashbacks within the main narrative and streamlined the manuscript as a whole, a process that brought a work that was in the neighborhood of 122,000 words to just under 100,000 in this version. These editorial decisions were mine, and I can only hope they would meet with Mohamedous approval.