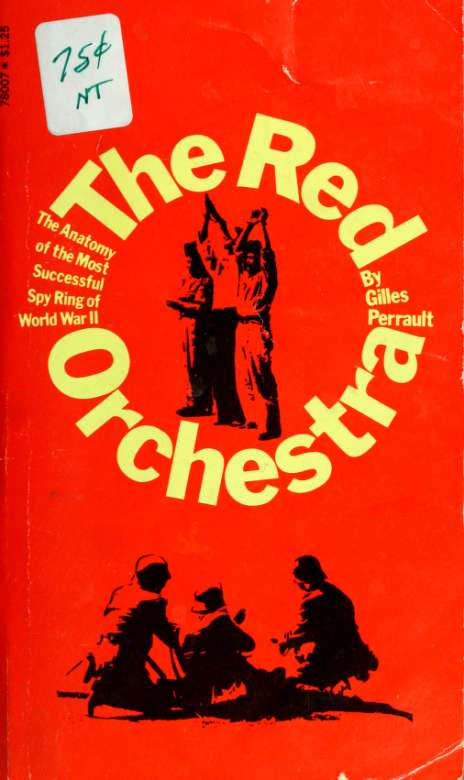

This book made available by the Internet Archive.

For My Parents,

Georges and Germaine Peyroles,

Who Played in Another Orchestra.

24-page photo insert appears in Part Two

OW IfmiiBfitId K4. - Ph. 68t>. 70t (BWad TCAY Soutli

Prelude

Walter Schmidt took off his earphones, scraped back his chair and tried to ease some life into his limbs. He felt tired and depressed. The signs of another June day had begun to appear above the horizon, but in the East Prussian summer the hours of darkness are soon counted. He looked at his watch. Three-thirty. His shift did not end until six, and meanwhile he had nothing whatever to do except stay tuned to the Nor-wegian Resistance. Strictly routine. The transmitter, tucked away in the mountains, was fed and operated by a small group of partisans. Night after night, at three forty-eight precisely, they made contact with London and relayed a message consisting of ten or a dozen coded groups. Schmidt knew that a team of German experts had been sent to Norway with orders to track down the secret station. Easier said than done: the mountains had a screening effect and made the signals hard to pinpoint. Attempts had been made to solve the problem from above, by installing direction finders in a small spotter plane. But as soon as the Fieseler Storch flew over the fjords, the transmitter went off the air. The crew would continue to hunt so long as their fuel lasted, then fly home empty-handed.

But they'd catch them in the end; they always did. And did it really matter? Schmidt was unable to work up much feeling about the Norwegian underground. The Norwegians were transmitting to London, and London was doomed. There seemed little point to recording all these messages and trying to break the code, when the originals would soon be readily obtainable from a London office. The Filhrer may have called off the invasion of Britain, but he was merely biding his time. The old lion was being kept as a tidbit, to be consumed at leisure after the Russian bear had been hacked to pieces. Four

days earlier, on June 22, 1941, German Panzer divisions had swarmed across the River Bug and flattened the Soviet frontier guards beneath their metal caterpillars. Since then, the High Command had been very sparing with details of the operations. This was a good sign. The same reticence had been displayed in May, 1940, at the start of the Battle of France what was the point of supplying the fleeing, disorganized French generals with valuable information? And now the Russian generals were in the same predicament, with no way of knowing exactly where the front lay. Why should the Wehr-macht tell them? In a few days, when the fighting was nearly over, Radio Berlin would put out a special communique, preceded as usual by the triumphant blare of trumpets, to announce the destruction of the Red Army. But Walter Schmidt would not join the victory parade below the walls of the Kremlin. He would still be here in Kranz, doggedly keeping track of the inconsequential messages of a phantom transmitter.

The Kranz monitoring station was within a few hundred yards of the Baltic. Schmidt stared despondently at the dunes above the beach. No gulls flying this morning they had retreated inland. Their absence meant there would almost certainly be a storm before the new day was over, but Schmidt did not know how to read the signs. He was from the Bavarian mountains. The bleakness of these Prussian wastes sapped his spirits; he felt more depressed than ever. He returned to his bench, put on the earphones, tuned the receiver to 15,465 kilocycles, the frequency employed by the Norwegian Resistance, and lethargically awaited the call-signal which would come speeding through the ether at three forty-eight precisely.

The three paragraphs above are more or less pure invention. I do not know the identity of the German radio operator responsible for tuning in to the Norwegian transmitter on the night of June 25-26, 1941. I have no information concerning his frame of mind. Nor am I familiar with the migratory urges, local or intercontinental, of Prussian seagulls; a storm may have been brewing over Kranz on June 26, 1941, but that is pure speculation.

Thus, although 1 have elected to show the radio operator at Kranz a Bavarian consumed with disappointment at his in

ability to join in the sweeping advance on the eastern front, I might equally well have depicted him as a fat sluggard thanking his lucky stars for being spared the choking dust of the Russian roads, or even as a fanatical Nazi waiting, stern-jawed, for those Norwegian Schweinhunde to transmit their message. The fact is that if I were to confine myself to the few authenticated items of information available, I should be restricted to writing as follows:

The monitoring station at Kranz had orders to intercept secret transmissions. On the night of June 25-26, 1941, one of the operators tuned in at the usual time to the frequency used by a Norwegian transmitter. But the call sign he picked up was not the one usually put out by the Norwegians; indeed, it was quite unknown to him: "KLK from PTX... KLK from PTX... KLK from PTX..." The call sign was followed by a message made up of several cipher groups. The operator reported his discovery and listed the frequency employed.

These quiet beginnings heralded a campaign which was to become a nightmare to ReichsfUhrer Himmler and Admiral Canaris, the heads of Germany's two secret services, and which eventually prompted Adolf Hitler to declare, on May 17, 1942, "The Bolsheviks are our superiors in only one field espionage." And at that time the Fiihrer had been given little more than a glimpse into the stunning achievements of the Red Orchestra.

PART ONE

The Network

1. The Schooling of a Leader

In the jargon of the German secret services, the head of a spy network was a Kapellmeister, a chef d'orchestre an orchestra leader who directed and coordinated the playing of his instrumentalists.

The hero of this story, Leopold Trepper, is a Polish Jew born in Neumarkt, near Zakopane, on February 23, 1904. His father, a traveling salesman, wore himself out in his efforts to provide for his wife and ten children. He died when young Leopold was nearly twelve. The boy proved unusually bright, and his family decided that no sacrifice was too great to give him a good start in life. At that time Poland was still in the grip of strong anti-Semitic traditions and subject to a military dictatorship; it was bled white by war and economic upheavals. These adverse conditions lengthened the odds against the Treppers. It was rather as if the survivors on the raft of the Medusa had donated their meager rations to one of their number, to give him strength to clamber to the top of the mast.